Home · Book Reports · 2024 · Atomic Habits

- Author :: James Clear

- Publication Year :: 2018

- Source :: Atomic_Habits_by_James_Clear.epub

designates my notes. / designates important. / designates very important.

Thoughts

Exceptional Quotes

- How to Create a Good Habit

- The 1st law (Cue): Make it obvious.

- The 2nd law (Craving): Make it attractive.

- The 3rd law (Response): Make it easy.

- The 4th law (Reward): Make it satisfying.

- How to Break a Bad Habit

- Inversion of the 1st law (Cue): Make it invisible.

- Inversion of the 2nd law (Craving): Make it unattractive.

- Inversion of the 3rd law (Response): Make it difficult.

- Inversion of the 4th law (Reward): Make it unsatisfying.

- Look at nearly any product that is habit-forming and you’ll see that it does not create a new motivation, but rather latches onto the underlying motives of human nature.

- Find love and reproduce = using Tinder

- Connect and bond with others = browsing Facebook

- Win social acceptance and approval = posting on Instagram

- Reduce uncertainty = searching on Google

- Achieve status and prestige = playing video games

Table of Contents

- 00: Introduction

- 01: The Surprising Power of Atomic Habits

- 02: How Your Habits Shape Your Identity (and Vice Versa)

- 03: How to Build Better Habits in 4 Simple Steps

- 04: The Man Who Didn’t Look Right

- 05: The Best Way to Start a New Habit

- 06: Motivation Is Overrated; Environment Often Matters More

- 07: The Secret to Self-Control

- 08: How to Make a Habit Irresistible

- 09: The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping Your Habits

- 10: How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits

- 11: Walk Slowly, but Never Backward

- 12: The Law of Least Effort

- 13: How to Stop Procrastinating by Using the Two-Minute Rule

- 14: How to Make Good Habits Inevitable and Bad Habits Impossible

- 15: The Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change

- 16: How to Stick with Good Habits Every Day

- 17: How an Accountability Partner Can Change Everything

- 18: The Truth About Talent (When Genes Matter and When They Don’t)

- 19: The Goldilocks Rule: How to Stay Motivated in Life and Work

- 20: The Downside of Creating Good Habits

- 21: Conclusion

The Fundamentals

The 1st Law - Make It Obvious

The 2nd Law - Make It Attractive

The 3rd Law - Make It Easy

The 4th Law - Make It Satisfying

Advanced Tactics

· Introduction

page 015:

-

The backbone of this book is my four-step model of habits—cue, craving, response, and reward—and the four laws of behavior change that evolve out of these steps. Readers with a psychology background may recognize some of these terms from operant conditioning, which was first proposed as “stimulus, response, reward” by B. F. Skinner in the 1930s

-

Human behavior is always changing: situation to situation, moment to moment, second to second.

-

What?

The Fundamentals

· Chapter 01 - The Surprising Power of Atomic Habits

page 021:

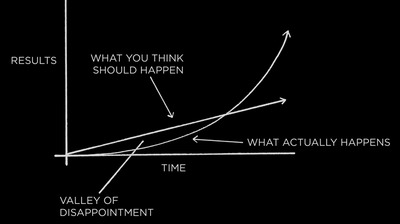

- Success is the product of daily habits—not once-in-a-lifetime transformations.

page 025:

- Prevailing wisdom claims that the best way to achieve what we want in life—getting into better shape, building a successful business, relaxing more and worrying less, spending more time with friends and family— is to set specific, actionable goals.

page 026:

-

For many years, this was how I approached my habits, too. Each one was a goal to be reached. I set goals for the grades I wanted to get in school, for the weights I wanted to lift in the gym, for the profits I wanted to earn in business. I succeeded at a few, but I failed at a lot of them. Eventually, I began to realize that my results had very little to do with the goals I set and nearly everything to do with the systems I followed.

-

What’s the difference between systems and goals? It’s a distinction I first learned from Scott Adams, the cartoonist behind the Dilbert comic. Goals are about the results you want to achieve. Systems are about the processes that lead to those results.

-

If you’re an entrepreneur, your goal might be to build a million-dollar business. Your system is how you test product ideas, hire employees, and run marketing campaigns.

page 027:

-

Imagine you have a messy room and you set a goal to clean it. If you summon the energy to tidy up, then you will have a clean room—for now. But if you maintain the same sloppy, pack-rat habits that led to a messy room in the first place, soon you’ll be looking at a new pile of clutter and hoping for another burst of motivation. You’re left chasing the same outcome because you never changed the system behind it.

-

In order to improve for good, you need to solve problems at the systems level. Fix the inputs and the outputs will fix themselves.

· Chapter 02 - How Your Habits Shape Your Identity (and Vice Versa)

page 032:

-

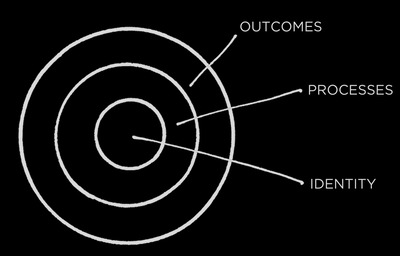

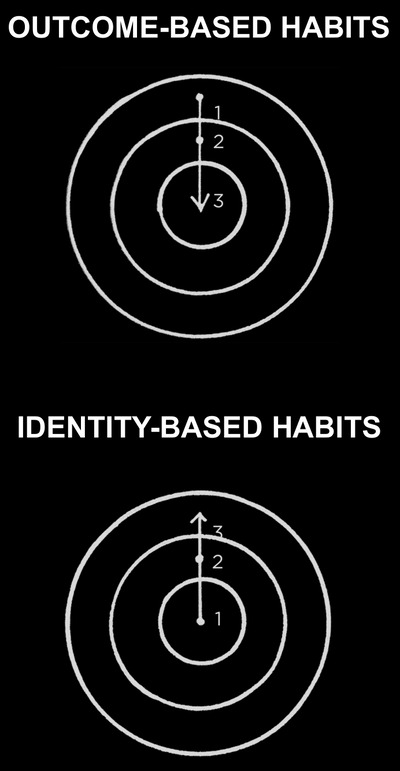

The first layer is changing your outcomes. This level is concerned with changing your results: losing weight, publishing a book, winning a championship. Most of the goals you set are associated with this level of change.

-

The second layer is changing your process. This level is concerned with changing your habits and systems: implementing a new routine at the gym, decluttering your desk for better workflow, developing a meditation practice. Most of the habits you build are associated with this level.

-

The third and deepest layer is changing your identity. This level is concerned with changing your beliefs: your worldview, your self-image, your judgments about yourself and others. Most of the beliefs, assumptions, and biases you hold are associated with this level.

-

Outcomes are about what you get. Processes are about what you do. Identity is about what you believe.

-

Many people begin the process of changing their habits by focusing on what they want to achieve. This leads us to outcome-based habits. The alternative is to build identity-based habits. With this approach, we start by focusing on who we wish to become.

page 033:

-

Imagine two people resisting a cigarette. When offered a smoke, the first person says, “No thanks. I’m trying to quit. It sounds like a reasonable response, but this person still believes they are a smoker who is trying to be something else. They are hoping their behavior will change while carrying around the same beliefs.

-

The second person declines by saying, “No thanks. I’m not a smoker. It’s a small difference, but this statement signals a shift in identity. Smoking was part of their former life, not their current one. They no longer identify as someone who smokes.

page 034:

- Behavior that is incongruent with the self will not last.

page 036:

- The more deeply a thought or action is tied to your identity, the more difficult it is to change it.

page 037:

- Becoming the best version of yourself requires you to continuously edit your beliefs, and to upgrade and expand your identity.

page 041:

-

The most effective way to change your habits is to focus not on what you want to achieve, but on who you wish to become.

-

Your identity emerges out of your habits. Every action is a vote for the type of person you wish to become.

-

Becoming the best version of yourself requires you to continuously edit your beliefs, and to upgrade and expand your identity.

-

The real reason habits matter is not because they can get you better results (although they can do that), but because they can change your beliefs about yourself.

· Chapter 03 - How to Build Better Habits in 4 Simple Steps

page 044:

- Habit formation is incredibly useful because the conscious mind is the bottleneck of the brain. It can only pay attention to one problem at a time. As a result, your brain is always working to preserve your conscious attention for whatever task is most essential. Whenever possible, the conscious mind likes to pawn off tasks to the nonconscious mind to do automatically. This is precisely what happens when a habit is formed. Habits reduce cognitive load and free up mental capacity, so you can allocate your attention to other tasks.

page 045:

- The process of building a habit can be divided into four simple steps: cue, craving, response, and reward.

page 051:

-

How to Create a Good Habit

- The 1st law (Cue): Make it obvious.

- The 2nd law (Craving): Make it attractive.

- The 3rd law (Response): Make it easy.

- The 4th law (Reward): Make it satisfying.

-

How to Break a Bad Habit

- Inversion of the 1st law (Cue): Make it invisible.

- Inversion of the 2nd law (Craving): Make it unattractive.

- Inversion of the 3rd law (Response): Make it difficult.

- Inversion of the 4th law (Reward): Make it unsatisfying.

The 1st Law - Make It Obvious

· Chapter 04 - The Man Who Didn’t Look Right

page 056:

- This is one of the most surprising insights about our habits: you don’t need to be aware of the cue for a habit to begin. You can notice an opportunity and take action without dedicating conscious attention to it. This is what makes habits useful.

page 058:

- Making a list of the things you do in your daily routine and then marking them as good, bad, or neutral habits can help you identify what you are doing right and what might need improving.

page 061:

-

Pointing-and-Calling raises your level of awareness from a nonconscious habit to a more conscious level by verbalizing your actions.

-

The Habits Scorecard is a simple exercise you can use to become more aware of your behavior.

· Chapter 05 - The Best Way to Start a New Habit

page 062:

-

implementation intention which is a plan you make beforehand about when and where to act. That is, how you intend to implement a particular habit.

-

I will [BEHAVIOR] at [TIME] in [LOCATION].

page 066:

- Habit stacking is a special form of an implementation intention. Rather than pairing your new habit with a particular time and location, you pair it with a current habit.

· Chapter 06 - Motivation Is Overrated; Environment Often Matters More

page 072:

-

Thorndike and her colleagues designed a six-month study to alter the “choice architecture” of the hospital cafeteria. They started by changing how drinks were arranged in the room. Originally, the refrigerators located next to the cash registers in the cafeteria were filled with only soda. The researchers added water as an option to each one. Additionally, they placed baskets of bottled water next to the food stations throughout the room. Soda was still in the primary refrigerators, but water was now available at all drink locations.

-

Over the next three months, the number of soda sales at the hospital dropped by 11.4 percent. Meanwhile, sales of bottled water increased by 25.8 percent. They made similar adjustments—and saw similar results—with the food in the cafeteria.

-

As in “Nudge”, these changes seem harmless or beneficial, but I suspect that the easily argued cases are used initially to demonstrate “choice architecture”. After these tactics are proven, they can be applied in much more manifold ways. I suspect they will/are employed to the benefit of the choice architect and less so to the end user/consumer. If you can manipulate people into buying water, can you not manipulate people into buying the more expensive product?

-

In the case of building habits for yourself, these tactics seem laudable.

page 073:

-

Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behavior.

-

In 1936, psychologist Kurt Lewin wrote a simple equation that makes a powerful statement: Behavior is a function of the Person in their Environment, or $B = f (P,E).$

page 074:

-

It didn’t take long for Lewin’s Equation to be tested in business. In 1952, the economist Hawkins Stern described a phenomenon he called Suggestion Impulse Buying, which “is triggered when a shopper sees a product for the first time and visualizes a need for it.” In other words, customers will occasionally buy products not because they want them but because of how they are presented to them.

-

For example, items at eye level tend to be purchased more than those down near the floor. For this reason, you’ll find expensive brand names featured in easy-to-reach locations on store shelves because they drive the most profit, while cheaper alternatives are tucked away in harder-to-reach spots. The same goes for end caps, which are the units at the end of aisles. End caps are moneymaking machines for retailers because they are obvious locations that encounter a lot of foot traffic. For example, 45 percent of Coca-Cola sales come specifically from end-of-the-aisle racks.

-

The more obviously available a product or service is, the more likely you are to try it. People drink Bud Light because it is in every bar and visit Starbucks because it is on every corner. We like to think that we are in control. If we choose water over soda, we assume it is because we wanted to do so. The truth, however, is that many of the actions we take each day are shaped not by purposeful drive and choice but by the most obvious option.

page 075:

- The most powerful of all human sensory abilities, however, is vision. The human body has about eleven million sensory receptors. Approximately ten million of those are dedicated to sight. Some experts estimate that half of the brain’s resources are used on vision.

page 078:

- Create a separate space for work, study, exercise, entertainment, and cooking. The mantra I find useful is One space, one use.”

· Chapter 07 - The Secret to Self-Control

page 083:

- Bad habits are autocatChapteralytic: the process feeds itself. They foster the feelings they try to numb. You feel bad, so you eat junk food. Because you eat junk food, you feel bad.

page 084:

-

The inversion of the 1st Law of Behavior Change is make it invisible.

-

People with high self-control tend to spend less time in tempting situations. It’s easier to avoid temptation than resist it.

The 2nd Law - Make It Attractive

· Chapter 08 - How to Make a Habit Irresistible

page 089:

-

The modern food industry, and the overeating habits it has spawned, is just one example of the 2nd Law of Behavior Change: Make it attractive. The more attractive an opportunity is, the more likely it is to become habit-forming.

-

Look around. Society is filled with highly engineered versions of reality that are more attractive than the world our ancestors evolved in. Stores feature mannequins with exaggerated hips and breasts to sell clothes. Social media delivers more “likes” and praise in a few minutes than we could ever get in the office or at home. Online porn splices together stimulating scenes at a rate that would be impossible to replicate in real life. Advertisements are created with a combination of ideal lighting, professional makeup, and Photoshopped edits—even the model doesn’t look like the person in the final image.

page 091:

-

When it comes to habits, the key takeaway is this: dopamine is released not only when you experience pleasure, but also when you anticipate it. Gambling addicts have a dopamine spike right before they place a bet, not after they win. Cocaine addicts get a surge of dopamine when they see the powder, not after they take it. Whenever you predict that an opportunity will be rewarding, your levels of dopamine spike in anticipation. And whenever dopamine rises, so does your motivation to act.

-

It is the anticipation of a reward—not the fulfillment of it—that gets us to take action.

-

Interestingly, the reward system that is activated in the brain when you receive a reward is the same system that is activated when you anticipate a reward. This is one reason the anticipation of an experience can often feel better than the attainment of it. As a child, thinking about Christmas morning can be better than opening the gifts. As an adult, daydreaming about an upcoming vacation can be more enjoyable than actually being on vacation. Scientists refer to this as the difference between “wanting” and “liking.”

page 092:

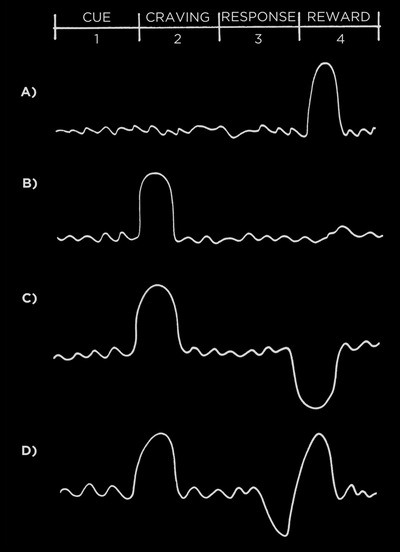

- FIGURE 9: Before a habit is learned (A), dopamine is released when the reward is experienced for the first time. The next time around (B), dopamine rises before taking action, immediately after a cue is recognized. This spike leads to a feeling of desire and a craving to take action whenever the cue is spotted. Once a habit is learned, dopamine will not rise when a reward is experienced because you already expect the reward. However, if you see a cue and expect a reward, but do not get one, then dopamine will drop in disappointment (C). The sensitivity of the dopamine response can clearly be seen when a reward is provided late (D). First, the cue is identified and dopamine rises as a craving builds. Next, a response is taken but the reward does not come as quickly as expected and dopamine begins to drop. Finally, when the reward comes a little later than you had hoped, dopamine spikes again. It is as if the brain is saying, “See! I knew I was right. Don’t forget to repeat this action next time.”

· Chapter 09 - The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping Your Habits

page 097:

-

In 1965, a Hungarian man named Laszlo Polgar wrote a series of strange letters to a woman named Klara.

-

Laszlo was a firm believer in hard work. In fact, it was all he believed in: he completely rejected the idea of innate talent. He claimed that with deliberate practice and the development of good habits, a child could become a genius in any field. His mantra was “A genius is not born, but is educated and trained.”

-

Laszlo believed in this idea so strongly that he wanted to test it with his own children—and he was writing to Klara because he “needed a wife willing to jump on board.” Klara was a teacher and, although she may not have been as adamant as Laszlo, she also believed that with proper instruction, anyone could advance their skills.

-

Laszlo decided chess would be a suitable field for the experiment, and he laid out a plan to raise his children to become chess prodigies. The kids would be home-schooled, a rarity in Hungary at the time. The house would be filled with chess books and pictures of famous chess players. The children would play against each other constantly and compete in the best tournaments they could find. The family would keep a meticulous file system of the tournament history of every competitor the children faced. Their lives would be dedicated to chess.

-

Laszlo successfully courted Klara, and within a few years, the Polgars were parents to three young girls: Susan, Sofia, and Judit.

-

Susan, the oldest, began playing chess when she was four years old. Within six months, she was defeating adults.

page 098:

-

Sofia, the middle child, did even better. By fourteen, she was a world champion, and a few years later, she became a grandmaster.

-

Judit, the youngest, was the best of all. By age five, she could beat her father. At twelve, she was the youngest player ever listed among the top one hundred chess players in the world. At fifteen years and four months old, she became the youngest grandmaster of all time— younger than Bobby Fischer, the previous record holder. For twenty- seven years, she was the number-one-ranked female chess player in the world.

-

The childhood of the Polgar sisters was atypical, to say the least. And yet, if you ask them about it, they claim their lifestyle was attractive, even enjoyable. In interviews, the sisters talk about their childhood as entertaining rather than grueling. They loved playing chess. They couldn’t get enough of it. Once, Laszlo reportedly found Sofia playing chess in the bathroom in the middle of the night. Encouraging her to go back to sleep, he said, “Sofia, leave the pieces alone!” To which she replied, “Daddy, they won’t leave me alone!”

-

The Polgar sisters grew up in a culture that prioritized chess above all else—praised them for it, rewarded them for it. In their world, an obsession with chess was normal. And as we are about to see, whatever habits are normal in your culture are among the most attractive behaviors you’ll find.

page 099:

- We imitate the habits of three groups in particular:

- The close.

- The many.

- The powerful.

page 100:

- One of the most effective things you can do to build better habits is to join a culture where your desired behavior is the normal behavior.

· Chapter 10 - How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits

page 108:

- Look at nearly any product that is habit-forming and you’ll see that it does

not create a new motivation, but rather latches onto the underlying motives of

human nature.

- Find love and reproduce = using Tinder

- Connect and bond with others = browsing Facebook

- Win social acceptance and approval = posting on Instagram

- Reduce uncertainty = searching on Google

- Achieve status and prestige = playing video games

page 110:

- When you binge-eat or light up or browse social media, what you really want is not a potato chip or a cigarette or a bunch of likes. What you really want is to feel different.

The 3rd Law - Make It Easy

· Chapter 11 - Walk Slowly, but Never Backward

page 117:

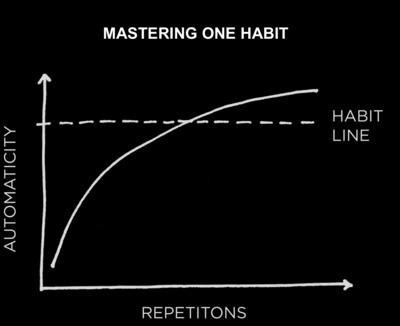

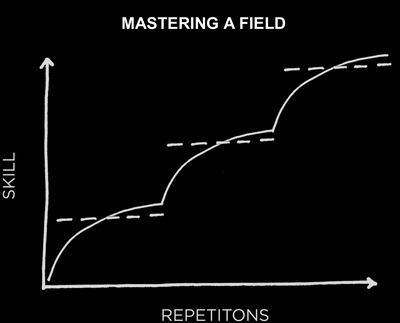

- If you want to master a habit, the key is to start with repetition, not perfection. You don’t need to map out every feature of a new habit. You just need to practice it. This is the first takeaway of the 3rd Law: you just need to get your reps in.

· Chapter 12 - The Law of Least Effort

page 124:

- In a sense, every habit is just an obstacle to getting what you really want. Dieting is an obstacle to getting fit. Meditation is an obstacle to feeling calm. Journaling is an obstacle to thinking clearly. You don’t actually want the habit itself. What you really want is the outcome the habit delivers.

page 129:

-

Human behavior follows the Law of Least Effort. We will naturally gravitate toward the option that requires the least amount of work.

-

Reduce the friction associated with good behaviors. When friction is low, habits are easy.

-

Increase the friction associated with bad behaviors. When friction is high, habits are difficult.

· Chapter 13 - How to Stop Procrastinating by Using the Two-Minute Rule

page 134:

-

use the Two-Minute Rule which states, “When you start a new habit, it should take less than two minutes to do.”

-

The idea is to make your habits as easy as possible to start. Anyone can meditate for one minute, read one page, or put one item of clothing away. And, as we have just discussed, this is a powerful strategy because once you’ve started doing the right thing, it is much easier to continue doing it. A new habit should not feel like a challenge. The actions that follow can be challenging, but the first two minutes should be easy. What you want is a “gateway habit” that naturally leads you down a more productive path.

page 138:

- Standardize before you optimize. You can’t improve a habit that doesn’t exist.

· Chapter 14 - How to Make Good Habits Inevitable and Bad Habits Impossible

page 139:

- Sometimes success is less about making good habits easy and more about making bad habits hard. This is an inversion of the 3rd Law of Behavior Change: make it difficult. If you find yourself continually struggling to follow through on your plans, then you can take a page from Victor Hugo and make your bad habits more difficult by creating what psychologists call a commitment device.

page 140:

- my friend and fellow habits expert Nir Eyal purchased an outlet timer, which is an adapter that he plugged in between his internet router and the power outlet. At 10 p.m. each night, the outlet timer cuts off the power to the router. When the internet goes off, everyone knows it is time to go to bed.

The 4th Law - Make It Satisfying

· Chapter 15 - The Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change

page 150:

-

The first three laws of behavior change—make it obvious, make it attractive, and make it easy—increase the odds that a behavior will be performed this time. The fourth law of behavior change—make it satisfying—increases the odds that a behavior will be repeated next time. It completes the habit loop.

-

But there is a trick. We are not looking for just any type of satisfaction. We are looking for immediate satisfaction.

page 151:

-

Behavioral economists refer to this tendency as time inconsistency. That is, the way your brain evaluates rewards is inconsistent across time.* You value the present more than the future. Usually, this tendency serves us well. A reward that is certain right now is typically worth more than one that is merely possible in the future. But occasionally, our bias toward instant gratification causes problems.

-

Every habit produces multiple outcomes across time. Unfortunately, these outcomes are often misaligned. With our bad habits, the immediate outcome usually feels good, but the ultimate outcome feels bad. With good habits, it is the reverse: the immediate outcome is unenjoyable, but the ultimate outcome feels good. The French economist Frédéric Bastiat explained the problem clearly when he wrote, “It almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the later consequences are disastrous, and vice versa. . . . Often, the sweeter the first fruit of a habit, the more bitter are its later fruits.”

page 152:

-

Put another way, the costs of your good habits are in the present. The costs of your bad habits are in the future.

-

let’s update the Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change: What is immediately rewarded is repeated. What is immediately punished is avoided.

· Chapter 16 - How to Stick with Good Habits Every Day

page 156:

-

Dyrsmid began each morning with two jars on his desk. One was filled with 120 paper clips. The other was empty. As soon as he settled in each day, he would make a sales call. Immediately after, he would move one paper clip from the full jar to the empty jar and the process would begin again. “Every morning I would start with 120 paper clips in one jar and I would keep dialing the phone until I had moved them all to the second jar,” he told me.

-

Within eighteen months, Dyrsmid was bringing in $5 million to the firm. By age twenty-four, he was making $75,000 per year—the equivalent of $125,000 today. Not long after, he landed a six-figure job with another company.

-

I like to refer to this technique as the Paper Clip Strategy

page 157:

-

Countless people have tracked their habits, but perhaps the most famous was Benjamin Franklin. Beginning at age twenty, Franklin carried a small booklet everywhere he went and used it to track thirteen personal virtues. This list included goals like Lose no time. Be always employed in something useful” and “Avoid trifling conversation.” At the end of each day, Franklin would open his booklet and record his progress.

-

Don’t break the chain” is a powerful mantra.

page 158:

- Habit tracking also keeps you honest. Most of us have a distorted view of our own behavior. We think we act better than we do.

page 159:

- In summary, habit tracking (1) creates a visual cue that can remind you to act, (2) is inherently motivating because you see the progress you are making and don’t want to lose it, and (3) feels satisfying whenever you record another successful instance of your habit.

page 162:

-

The dark side of tracking a particular behavior is that we become driven by the number rather than the purpose behind it.

-

We focus on working long hours instead of getting meaningful work done. We care more about getting ten thousand steps than we do about being healthy. We teach for standardized tests instead of emphasizing learning, curiosity, and critical thinking. In short, we optimize for what we measure. When we choose the wrong measurement, we get the wrong behavior.

· Chapter 17 - How an Accountability Partner Can Change Everything

page 167:

- Just as governments use laws to hold citizens accountable, you can create a habit contract to hold yourself accountable. A habit contract is a verbal or written agreement in which you state your commitment to a particular habit and the punishment that will occur if you don’t follow through. Then you find one or two people to act as your accountability partners and sign off on the contract with you.

Advanced Tactics

· Chapter 18 - The Truth About Talent (When Genes Matter and When They Don’t)

page 175:

- As Robert Plomin, a behavioral geneticist at King’s College in London, told me, “It is now at the point where we have stopped testing to see if traits have a genetic component because we literally can’t find a single one that isn’t influenced by our genes.”

page 178:

-

What feels like fun to me, but work to others? The mark of whether you are made for a task is not whether you love it but whether you can handle the pain of the task easier than most people. When are you enjoying yourself while other people are complaining? The work that hurts you less than it hurts others is the work you were made to do.

-

What makes me lose track of time? Flow is the mental state you enter when you are so focused on the task at hand that the rest of the world fades away. This blend of happiness and peak performance is what athletes and performers experience when they are “in the zone.” It is nearly impossible to experience a flow state and not find the task satisfying at least to some degree.

page 180:

- A good player works hard to win the game everyone else is playing. A great player creates a new game that favors their strengths and avoids their weaknesses.

· Chapter 19: The Goldilocks Rule: How to Stay Motivated in Life and Work

page 183:

- Steve Martin faced this fear every week for eighteen years. In his words, “10 years spent learning, 4 years spent refining, and 4 years as a wild success.”

page 184:

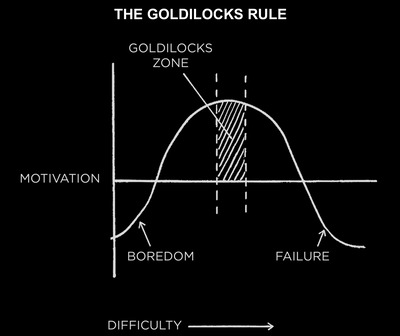

- The Goldilocks Rule states that humans experience peak motivation when working on tasks that are right on the edge of their current abilities. Not too hard. Not too easy. Just right.

page 185:

- A flow state is the experience of being “in the zone” and fully immersed in an activity. Scientists have tried to quantify this feeling. They found that to achieve a state of flow, a task must be roughly 4 percent beyond your current ability.

page 186:

- As Machiavelli noted, “Men desire novelty to such an extent that those who are doing well wish for a change as much as those who are doing badly.”

· Chapter 20 - The Downside of Creating Good Habits

page 196:

-

In the beginning, repeating a habit is essential to build up evidence of your desired identity. As you latch on to that new identity, however, those same beliefs can hold you back from the next level of growth. When working against you, your identity creates a kind of “pride” that encourages you to deny your weak spots and prevents you from truly growing. This is one of the greatest downsides of building habits.

-

The tighter we cling to an identity, the harder it becomes to grow beyond it.

-

One solution is to avoid making any single aspect of your identity an overwhelming portion of who you are. In the words of investor Paul Graham, “keep your identity small.” The more you let a single belief define you, the less capable you are of adapting when life challenges you.

page 197:

- The following quote from the Tao Te Ching encapsulates the ideas perfectly: Men are born soft and supple; dead, they are stiff and hard. Plants are born tender and pliant; dead, they are brittle and dry. Thus whoever is stiff and inflexible is a disciple of death. Whoever is soft and yielding is a disciple of life. The hard and stiff will be broken. The soft and supple will prevail. —LAO TZU

· Chapter 21 - Conclusion

page 200:

- Success is not a goal to reach or a finish line to cross. It is a system to improve, an endless process to refine.

10.5. Appendix

page 204:

-

Awareness comes before desire. A craving is created when you assign meaning to a cue. Your brain constructs an emotion or feeling to describe your current situation, and that means a craving can only occur after you have noticed an opportunity.

-

Happiness is simply the absence of desire. When you observe a cue, but do not desire to change your state, you are content with the current situation. Happiness is not about the achievement of pleasure (which is joy or satisfaction), but about the lack of desire. It arrives when you have no urge to feel differently. Happiness is the state you enter when you no longer want to change your state.

page 205:

-

It is the idea of pleasure that we chase. We seek the image of pleasure that we generate in our minds. At the time of action, we do not know what it will be like to attain that image (or even if it will satisfy us). The feeling of satisfaction only comes afterward. This is what the Austrian neurologist Victor Frankl meant when he said that happiness cannot be pursued, it must ensue. Desire is pursued. Pleasure ensues from action.

-

Peace occurs when you don’t turn your observations into problems. The first step in any behavior is observation. You notice a cue, a bit of information, an event. If you do not desire to act on what you observe, then you are at peace.

-

With a big enough why you can overcome any how. Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher and poet, famously wrote, “He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.” This phrase harbors an important truth about human behavior. If your motivation and desire are great enough (that is, why are you are acting), you’ll take action even when it is quite difficult. Great craving can power great action—even when friction is high.

-

Being curious is better than being smart. Being motivated and curious counts for more than being smart because it leads to action. Being smart will never deliver results on its own because it doesn’t get you to act. It is desire, not intelligence, that prompts behavior. As Naval Ravikant says, “The trick to doing anything is first cultivating a desire for it.”

-

Emotions drive behavior. Every decision is an emotional decision at some level. Whatever your logical reasons are for taking action, you only feel compelled to act on them because of emotion. In fact, people with damage to emotional centers of the brain can list many reasons for taking action but still will not act because they do not have emotions to drive them. This is why craving comes before response. The feeling comes first, and then the behavior.

page 206:

-

We can only be rational and logical after we have been emotional. The primary mode of the brain is to feel; the secondary mode is to think. Our first response—the fast, nonconscious portion of the brain—is optimized for feeling and anticipating. Our second response—the slow, conscious portion of the brain—is the part that does the “thinking.”

-

Psychologists refer to this as System 1 (feelings and rapid judgments) versus System 2 (rational analysis). The feeling comes first (System 1); the rationality only intervenes later (System 2). This works great when the two are aligned, but it results in illogical and emotional thinking when they are not.

-

Your response tends to follow your emotions. Our thoughts and actions are rooted in what we find attractive, not necessarily in what is logical.

-

Suffering drives progress. The source of all suffering is the desire for a change in state. This is also the source of all progress.

-

Your actions reveal how badly you want something. If you keep saying something is a priority but you never act on it, then you don’t really want it. It’s time to have an honest conversation with yourself. Your actions reveal your true motivations.

page 207:

-

Reward is on the other side of sacrifice. Response (sacrifice of energy) always precedes reward (the collection of resources). The “runner’s high” only comes after the hard run. The reward only comes after the energy is spent.

-

Self-control is difficult because it is not satisfying. A reward is an outcome that satisfies your craving. This makes self-control ineffective because inhibiting our desires does not usually resolve them.

-

Our expectations determine our satisfaction. The gap between our cravings and our rewards determines how satisfied we feel after taking action. If the mismatch between expectations and outcomes is positive (surprise and delight), then we are more likely to repeat a behavior in the future. If the mismatch is negative (disappointment and frustration), then we are less likely to do so.

-

This is the wisdom behind Seneca’s famous quote, Being poor is not having too little, it is wanting more.”

page 208:

-

Desire initiates. Pleasure sustains. Wanting and liking are the two drivers of behavior. If it’s not desirable, you have no reason to do it. Desire and craving are what initiate a behavior. But if it’s not enjoyable, you have no reason to repeat it. Pleasure and satisfaction are what sustain a behavior. Feeling motivated gets you to act. Feeling successful gets you to repeat.

-

Hope declines with experience and is replaced by acceptance. The first time an opportunity arises, there is hope of what could be. Your expectation (cravings) is based solely on promise. The second time around, your expectation is grounded in reality. You begin to understand how the process works and your hope is gradually traded for a more accurate prediction and acceptance of the likely outcome.

-

As Aristotle noted, Youth is easily deceived because it is quick to hope.”

page 281:

- The discovery of variable rewards happened by accident. One day in the lab, the famous Harvard psychologist B. F. Skinner was running low on food pellets during one experiment and making more was a time-consuming process because he had to manually press the pellets in a machine. This situation led him to “ask myself why every press of the lever had to be reinforced.” He decided to only give treats to the rats intermittently and, to his surprise, varying the delivery of food did not decrease behavior, but actually increased it.

page 285:

- Sorites is derived from the Greek word sorós, which means heap or pile.