Home · Book Reports · 2023 · Storey's Guide to Raising Rabbits

- Author :: Bob Bennett

- Publication Year :: 2018

- Read Date :: 2023-03-28

- Source :: storeys_guide_to_raising_rabbits.pdf

designates my notes. / designates important. / designates very important.

Thoughts

He goes on and on about how registered and pedigreed breeds are the only way to go. Sounds like some totalitarian bullshit. People have bred animals for a long time with no such systems. That said, I have been convinced that you would be better getting your first 3-4 breeders from a reputable place that keeps records. After that, if you are planning to eat them as I am, there seems to be little reason to register them. Still you would keep records for the ones you keep for breeding. If you want to sell breeding stock, then I think excellent records would be a necessity.

Wire cages aren’t harmful to the feet and allow the best circulation. Also the waste drops through to keep the cage clean with little effort on your part.

Presents a 4:1 feed conversion for the typical rabbit. In other reading I have done I see 3:1 for New Zealand’s. This makes sense since the New Zealand’s are bred for meat production. Using 2023 prices for pellets and a 3:1 ratio, one should expect to pay about $1.33 per pound for fryer meat. This does not include the costs associated with keeping the bucks/does.

Pushes pellets only for fastest growth. I would tend to agree, but I am wondering how much money could be saved supplementing them with grass/etc with the knowledge that they will grow slower. For me, producing 2 dozen rabbits a year to eat would be more than enough. If I could lower my costs and still hit this number, I don’t really care if they take 16 weeks instead of 8 weeks (for New Zealands) to reach fryer size.

Table of Contents

- 01: Why Start?

- 02: The Right Rabbit

- 03: Obtaining the Right Foundation Stock

- 04: A Gallery of Breeds

- 05: Housing and Equipment

- 06: Feeding Rabbits Right

- 07: Breeding and Producing Rabbits

- 08: To the Best Market: Selling Rabbits

- 09: Rabbits and the Home Garden

- 10: Preventing Problems

- 11: On to the Rabbit Shows

- 12: Rabbit Associations and the Future of the Industry

- 13: Cooking Rabbit

Part 1: Getting Started

Part 2: Housing, Feeding, and Breeding

Part 3: Marketing and Miscellany

Part 1: Getting Started

· Chapter 01: Why Start?

page 2 (pdf 19):

- Rabbit meat exceeds beef, pork, lamb, and chicken in protein content. It has a lower percentage of fat, less cholesterol, and fewer calories than any other meat you can buy.

· Chapter 02: The Right Rabbit

page 7 (pdf 24):

-

The American Rabbit Breeders Association (ARBA) recognizes about 50 individual breeds of domestic rabbits

-

It is not a rodent, either, but a lagomorph, a gnawing mammal of the order Lagomorpha.

page 9 (pdf 26):

-

Americans raise more New Zealand Whites for meat than any other breed. Next in line are Californians, followed — not necessarily in this order — by Satins, Champagne D’Argents, American Chinchillas, and Palominos. Other breeds taste just as good, but certain other considerations set some breeds apart from the rest.

-

The most obvious advantage of raising these breeds is that New Zealands and Californians wear white pelts. Many proces- sors sell the pelts and prefer white because it can be dyed any color.

page 11 (pdf 28):

- Tans never reach 4 pounds (1.8 kg) in 8 weeks, but they will weigh 3 pounds (1.4 kg) by that time. I often dress them out at 10 to 12 weeks, when they deliver about as much meat as an 8-week New Zealand because there is less bone. Florida Whites perform as well or better

page 12 (pdf 29):

-

because Americans prefer a young fryer-broiler, the fur is immature and unsuitable for durable garments.

-

Europeans have cornered the commercial garment market. If you see a coat advertised as made of “French rabbit,” it doesn’t mean that France has better rabbits than anybody else does. It simply means that the French will butcher a 10-pound (4.5 kg) rabbit for the table in midwinter when the hide is mature, thick, and prime. Remember, however, that even “French rabbit” is no match for mink and several other furbearers with considerably thicker pelts made into much longer-wearing garments.

page 20 (pdf 37):

- the Flemish Giant, the largest, which can weigh 20 pounds (9.1 kg) and even more, and the Giant Chinchilla and the Checkered Giant, each of which weighs up to 16 pounds (7.3 kg).

page 21 (pdf 38):

-

feed-to-meat conversion ratio makes them less profitable than the medium breeds. (4:1)

-

Medium-weight rabbits reach 9 to 12 pounds (4.1 to 5.4 kg) at maturity. Among the most popular are the New Zealand Whites, Californians, Satins, Palominos, and Champagne D’Argents. Meat producers prefer this group because their ideal rabbit is a meaty, fine-boned fryer weighing 4 pounds (1.8 kg) or more at 8 weeks of age.

page 22 (pdf 39):

-

Coat type can be classified as normal, rex, satin, or wool.

-

Normal-furred rabbits dominate the species. You will find varieties in each weight group. The Flemish Giant, the New Zealand, the Tan, and the Netherland Dwarf all have this type of fur. Normal fur is about an inch (2.5 cm) long. When stroked toward the rabbit’s head, good normal fur returns quickly to its natural position and lies smoothly over the body. The underfur is fine, soft, and dense.

-

Rex fur is worn, naturally, by Rex rabbits, which are in the medium-weight group, and by the Mini Rex, among the smallest rabbits. Velvety and plushlike, rex fur stands upright and has guard hairs almost as short as the undercoat. Rex fur is only about 5⁄8 inch (1.6 cm) long.

page 23 (pdf 40):

-

Satin fur consists of a small-diameter hair shaft and a more transparent hair shell than is displayed in normal fur. This greater transparency of the outer hair shell gives the Satin fur more intense color and more sheen than normal-furred breeds, with the exceptions of the Tan and the Havana, which have coats that lie flatter than those of other breeds, thus presenting more luster and sheen. Satin fur is about an inch (2.5 cm) long, like normal fur.

-

We can more properly describe the coat of the Angora rabbit as wool. Angoras, small- to medium-size rabbits, appear quite large because of their fluffy wool coats, which are 3 to 8 inches (7.6 to 20.3 cm) long.

· Chapter 03: Obtaining the Right Foundation Stock

page 27 (pdf 44):

-

should you care if the rabbits you are going to raise only to sell as pets or laboratory animals or simply to eat have a pedigree or registration certificate behind them?

-

Well, it not only matters, it is vital if you are to start right and be a success. That’s what this book is all about, and if it could have only one chapter, this would be it.

page 31 (pdf 48):

-

A junior rabbit is younger than 6 months; a senior rabbit is 6 months of age or older (8 months for the medium and giant breeds)

-

A couple of junior bucks, a junior doe, and a bred senior doe make an ideal start. If you ask for two junior bucks and a junior doe, you should expect to get them from the very best of the top breeders in the herd. The senior doe might be as old as 2 years and may have only a year or so of breeding life left. Nevertheless, if this doe has been producing in a good rabbitry for 18 months already, she must be pretty good to have hung around for so long. Ask to have the senior doe bred to the best buck the owner recommends. By the time she’s ready to mate again, the junior bucks will be mature. The junior doe will also be ready for mating. So in three or four months, you could have your original four rabbits, a litter of youngsters, and two more litters on the way.

page 35 (pdf 52):

- The average doe bears litters for about 3 years. Bucks will sire litters for 6 to 9 years.

page 36 (pdf 53):

- Average Prices of Breeding Stock:

· Chapter 04: A Gallery of Breeds

page 44 (pdf 61):

Californian

IDEAL WEIGHT: 9 pounds (4.0 kg)

VARIETIES: One

FUR TYPE: Normal; all white except for black nose, ears, and feet

MARKET: Number-two meat rabbit; often crossed with New Zealand White

Despite its black nose, ears, and feet, for all practical purposes this is a

white-pelted, pink-eyed, normal-furred breed with an excellent reputation as a

meat producer. Its fine bones make for an efficient meat breed, and its meat

is second only to the New Zealand White in popu- larity on the table. The depth

of the body should equal its width, and the ideal specimen is plump with well-

developed shoulders. The hindquarters are deep, round, and smooth, the loin is

broad and deep, and the overall picture is one of roundness.

page 45 (pdf 62):

Champagne d’Argent

IDEAL WEIGHT: Buck, 10 pounds (4.5 kg); doe, 10.5 pounds (4.8 kg)

VARIETIES: One; the French word argent means “silver,” and that is the only

color.

FUR TYPE: Normal. The adult body color is a bluish white, interspersed with

long jet-black hairs, from a distance giving the effect of old silver.

MARKET: A superb meat rabbit

The French word argent means silver, but if you see a preweaned litter of

Champagnes you might wonder, because they are adorned with jet-black normal

fur. They gradually change to the champagne color over the first months of

life, with only their muzzles remaining black. A superb meat rabbit, this

breed has a better dressout than New Zealands and Californians because of its

extremely fine bone.

page 46 (pdf 63):

New Zealand

IDEAL WEIGHT: 10–11 pounds (4.5–5.0 kg)

VARIETIES: White, Black, Red, Broken

FUR TYPE: Normal

MARKET: Number-one meat and laboratory rabbit (White); with fine bones

efficiently converts feed to meat; produces most consistently of all breeds.

Widely available: a great first choice; a great only choice

Almost every big white rabbit you encounter will be a New Zealand, or at least

one with New Zealand breeding behind it. But New Zealands also come in Black,

Red, and the relatively new Broken. The White is the number-one meat and

laboratory rabbit; the Red is the original; the Black has been around for

years. The Broken variety is largely white with blotches of either red or

black.

page 48 (pdf 65):

Rex

IDEAL WEIGHT: 8–9 pounds (3.6–4.1 kg)

VARIETIES: Amber, Black, Black Otter, Blue, Californian, Castor, Chinchilla,

Chocolate, Lilac, Lynx, Opal, Red, Sable, Seal, White, Broken

FUR TYPE: Rex, or short and plushlike; like velour or velvet.

MARKET: Meat, primarily; fur, secondarily, if raised to maturity when pelt is

prime.

An excellent meat rabbit, the plushlike Rex comes in 16 varieties, representing

almost all recognized colors of domestic rabbits. Velour or velvet come to mind

when stroking the fur. The pelt, with hair 5⁄8 inch long when prime, can bring

attractive prices at certain times. The Rex has the build of a meat rabbit, but

poorly furred footpads make it prone to sore hocks when raised on wire floors;

look for well-furred footpads.

Part 2: Housing, Feeding, and Breeding

· Chapter 05: Housing and Equipment

page 69 (pdf 86):

- each mature male will need its own space, to prevent fighting and possible injury. Young growing does can live in harmony as a group for the early months of their lives.

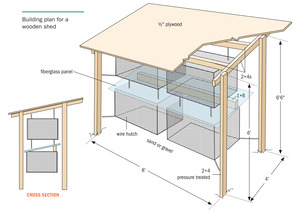

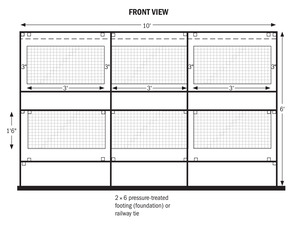

page 78 (pdf 95):

page 79 (pdf 96):

-

A doe raising a litter needs a hutch with square footage nearly that of her adult body weight. For example, I have 5-pound does in hutches that are 2½ × 2 feet, or 5 square feet. This rule of thumb is for rabbits whose litters are weaned at eight weeks. Some raisers wean them earlier and thus use a smaller hutch.

-

Don’t put hutches too close to the walls of the building. If you place your wire hutches against walls, or only inches away, those walls soon will be sprayed with urine, coated with molted hair, and even caked with manure.

-

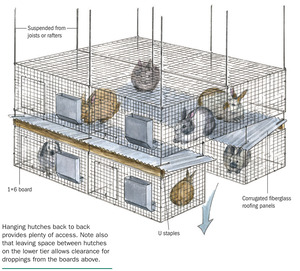

Hang hutches from the ceiling joists or rafters. Wire and S hooks work well.

-

Hang hutches back to back, particularly if you plan to put in an automatic watering system. Such a configuration helps you keep hutches well away from walls and in the center of the building, with a walkway all around.

-

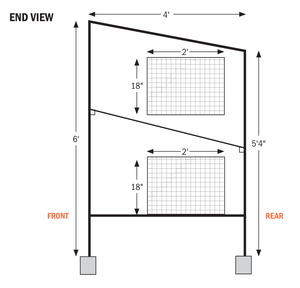

If you plan to have two or more tiers of hutches back to back, leave space between the back walls of the lower tiers. This allows for clearance of droppings from dropping boards above. One easy way to allow for that — the way I do it — is to use smaller hutches on the bottom tier. In my barn, each hutch in the top tier is 30 inches deep, front to back, but the bottom tier hutches are only 18 inches deep. That leaves 2 feet of clearance, which is more than adequate. You could easily use hutches 24 inches deep or even 30 inches deep on the bot- tom tier if you pulled that tier forward 6 inches, leaving a foot of clearance in either case. The smaller hutches are fine for breeding bucks and growing juniors. The lower tier is usually cooler, too, which is good for bucks.

page 81 (pdf 98):

- To construct a manure scraper that exactly matches the contours of the corrugated dropping boards, cut a 6 × 4-inch piece of fiberglass with the tin snips and screw it to a wooden handle (made from a length of a broomstick or any handy small dowel).

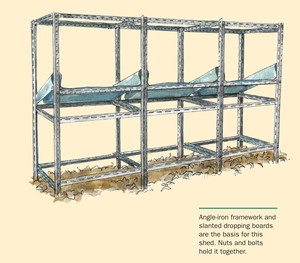

page 90 (pdf 107):

page 91 (pdf 108):

page 92 (pdf 109):

page 93 (pdf 110):

page 95 (pdf 112):

- White fiberglass admits light but reflects heat. It also lets you view the rabbits in a more natural light than does the green fiberglass. Don’t use clear fiberglass, however. It admits more light but also more heat.

page 96 (pdf 113):

page 103 (pdf 120):

-

Most rabbits drink a quart (or liter) or so of water per day. In hot weather, they drink more and in cold weather, less.

-

a nest box for the doe and her litter. A box 18 inches long, 10 inches wide, and 10 inches high is big enough for all but the giant breeds, which need a box about 24 inches long and 15 inches wide.

-

Don’t build or buy a covered nest box. These are damp, which can be fatal to your rabbits. I don’t care how cold it gets where you are; an open box is better than a closed one.

page 103 (pdf 120):

page 104 (pdf 121):

-

A popular style of box is one made of welded wire, such as is used on the floor of rabbit hutches, and lined with cardboard in cold weather. Don’t use a cardboard box alone, how- ever, as it may turn over, destroying the nest and the babies along with it. Rabbits will also chew it to pieces in short order. Always have a new, clean cardboard liner for the welded wire box. In warm weather, use cardboard on the bottom only so air can circulate through the wire-mesh sides.

-

Ideal temperature in a heated, air-conditioned, and insulated controlled environment would be 50°F (10°C). But remember that rabbits can take just about any amount of cold, because their fur keeps them warm. When temperatures get above 90°F (32°C), some rabbit raisers fill plastic jugs with water, freeze them, and place them in hutches to help cool their animals. Good insulation and ventilation are vital in hot weather. Fans are sometimes useful. Misting fans attached to garden hoses are quite effective in extremely hot temperatures.

· Chapter 06: Feeding Rabbits Right

page 107 (pdf 124):

-

The pellets contain everything the rabbit needs:

- Alfalfa hay for high-quality roughage

- Special sources of protein, including some of animal origin

- Phosphorus, calcium, essential trace minerals

- Necessary vitamins

-

Protein levels of these pellets range from 12 to 20 percent. A 16-percent protein level is sufficient for milk production in a doe bringing up a litter and for a growing rabbit. Higher protein levels really are not necessary. My preference is for the 16-percent feeds, which have high-fiber percentages to help prevent digestive problems.

page 108 (pdf 125):

-

Dry roughages include alfalfa hay, clover, lespedeza, oat hay, peanut hay, soybeans, timo- thy, and vetch. Greens that provide sources of rabbit feed are carrot, rutabaga, sweet potato, and turnip greens, along with lettuce. Wash all greens thoroughly.

-

Among the concentrates are barley, dried beet pulp, bread, brewer’s yeast, buckwheat, corn, cottonseed and linseed meals, milk, oats, peanut meal, sorghum meal, soybean meal, and wheat. If you like, you can mix up rations from these items, calculating the percentage of protein, roughage, and fat they will deliver to your rabbits. Some of the grains will have to be ground, cracked, or rolled.

-

Don’t ever feed greens to young rabbits. Greens can give the youngsters diarrhea and can kill them.

page 109 (pdf 126):

-

Alfalfa hay is my first choice for a hay supplement. I know the rabbits enjoy it, even though they already get a lot of alfalfa in the pellets. If they don’t clean up all their pellets, they don’t get the hay.

-

Young, growing, unweaned, and just-weaned rabbits should be fed all the rabbit pellets they will eat in a day. You will soon find out how much to feed. A lot depends on the size and age of your rabbits. If feed is left over the following day, give less. If a rabbit greets you at feeding time by diving headlong into its feed, give more.

-

Adult rabbits of the medium-weight group consume about 5 ounces (142 g) of pellets a day

-

Females with litters should have pellets available to them at all times. But watch out for overly fat does, especially those five to six months old and soon to be mated. Lazy bucks are probably overfed. In fact, most rabbits are probably overfed. Except for does with litters, rabbits do not need feed in front of them constantly.

-

My adult bucks and my does without litters usually clean up all their pellets within an hour, and that’s all they get until the next day. Of course, they almost always have hay to munch on.

page 110 (pdf 127):

-

If there is one best time of day to feed rabbits, it’s in the evening. They are more active at night and will eat more readily when day is done. But if morning is more convenient, your rabbits will adjust to your schedule. Rabbits do, however, require regularity.

-

a former president of the American Rabbit Breeders Association, shared with members a special mixture that he felt did a good job of supplementing rabbit pellets. If you are interested in making the effort to feed rabbits the way he did, here’s how it goes:

- 6 quarts oats

- 1 quart wheat

- 1 quart sunflower seeds

- 1 quart barley (whole if available, otherwise crimped)

- 1 quart kaffir corn (when available)

-

Mix oats, wheat, sunflower seeds, barley, and kaffir corn.

-

Feed one part of this mixture to three parts of pellets daily.

- “Since I’m retired and have time,” Oren said, “I feed the pellets at night and the grain in the morning. They can be fed together, but some animals like one ingredient better than others and will scratch out the other feed to get to it.”

page 111 (pdf 128):

- Until a full-grown, adult doe is pregnant, she gets only enough feed to keep her slim and trim.

page 112 (pdf 129):

-

I provide the doe and litter with all the pellets they want. That means I keep the self-feeder loaded to the point where it never runs out. They have all they want because the young should grow at a steady pace, and the doe needs to keep up her milk supply while the litter is nursing.

-

When I wean the litter, which I do at 6 to 10 weeks (see chapter 7), I give them all the rabbit pellets they will clean up in one day. I don’t let any feed hang around in the dish

-

I always give hay. I particularly like to give hay to the youngsters, and I believe that you really can’t overdo the fiber for the young. The more fiber you give the weanlings, the less chance they have of getting diarrhea

-

I never give any greens to rabbits less than 4 or 5 months of age under any circumstances.

page 113 (pdf 130):

- the main thing to remember about feeding bucks is to keep them slim and trim.

· Chapter 07: Breeding and Producing Rabbits

page 115 (pdf 132):

- To get into production, you must mate that first pair. For the small breeds, your does and bucks should be at least 5 months of age. The medium breeds should be 6 months old, and the giants must be at least 8 months of age.

page 116 (pdf 133):

-

take the doe to the buck’s hutch and put her in. Never take the buck to the doe, or they may fight, as the doe can be very defensive about her quarters. And never simply leave the pair alone together. Put the doe in with the buck, and stick around to observe the mating.

-

Don’t blink, or you may miss it. Rabbits are rabbits. They mate like rabbits. If everything goes right, and it usually does, it will be all over before you close the hutch door. The buck will have mounted the doe. The doe will have raised her hindquarters. The buck will have serviced the doe and fallen over backward or on his side.

-

Now remove the doe. Turn her over and check the vulva to make sure the semen has been deposited there.

page 117 (pdf 134):

-

I put the doe back in the buck’s hutch 8 to 10 hours after the first successful service. If the eggs are descending, now’s the time for conception.

-

Pick the buck up and put him on the doe’s back. He probably will get the idea. If that doesn’t work, leave the doe in his hutch, but take him out. Put him in hers, and leave them there overnight. He will pick up her scent and by the next day doubtless will be more interested. At that time take her to her own hutch and put her in; the buck will probably service her. She also should be more interested, having acquired his scent from his hutch.

page 123 (pdf 140):

-

Most does won’t mind accepting young from other mothers, and if the young in both litters are within a few days of the same age, they will do nicely. But don’t put a brand-new baby in with older and larger bunnies because it will never survive in the fight for the nipple. If a doe is nervous, or you simply aren’t sure whether she will accept another youngster, rub a little vanilla extract on her nose, which will make it difficult for her to smell anything else. This smell will linger long enough for the newcomer to pick up the scent of the rest of the litter, and that’s all it takes to gain social acceptance in the nest box.

-

You can remove the nest box when the litter is 3 weeks old in warm weather and 4 weeks old in winter.

-

my own practice is to rebreed the doe when the litter is 4 or 5 weeks old and wean the young at 6 or 7 weeks. That gives her one to two weeks without the litter to regain her strength for the next litter. And that gives me the potential for about five or six litters per year per doe.

page 124 (pdf 141):

-

It isn’t necessary to wean the litter at 8 weeks if you breed the doe again at that time; the litter may stay with her another couple of weeks. If she isn’t bred again, the young may stay until they don’t seem to be getting along — usually at about 3 months old. You may leave young does with their mother almost indefinitely. Mothers and daughters get along just fine for months.

-

Don’t remove all the youngsters at the same time, because you want the doe to dry up gradually. Take out the biggest and huskiest of the youngsters; let the little ones stay in for some more milk. If you wean the litter over a period of about a week, the gradual process will be better for both mother and young. You may keep the litter in one hutch for another month (up to age 3 months), but after that time you will have to give each buck his own hutch, and it’s best to have a hutch for each young doe, although two to a hutch is a satisfactory arrangement. If necessary, you can keep several does in one hutch, because they will continue to get along, but each buck needs his own, or battles will ensue. All does to be mated need their own hutches.

-

You will find it most economical to slaughter or market medium-size meat rabbits at 8 weeks or so

-

It is difficult to measure a rabbit’s worth at 8 weeks, especially when it comes to body type. Former ARBA president Oren Reynolds always said that a rabbit has “all the rear end it will ever have the day it is born,” but it takes a while to see how the shoulders will develop. If you are raising replacement or additional breeders, you will simply have to develop your rabbits for at least another month or so, depending on the breed

page 125 (pdf 142):

-

Electric heating pads, encased in sheet metal, are made to fit the bottoms of the all-wire nest boxes and may be purchased very economically. If they save just one litter, they pay for themselves.

-

Many breeders take advantage of the wire top of the hutch, provided the hutch is under a roof, and place an aluminum photo-reflector light over the nest box, so that heat from a bulb radiates down into the hutch. Others place such a light under the wire floor of the hutch below the nest box, and the litter burrows down into warmth. Ceramic infrared heater bulbs, sold in pet stores for reptile enclosures, also work well. Such practices really are nec- essary only on the day or night of kindling, or perhaps for a day or two after in really cold weather. By that time, the young begin to gain some fur and can stand the cold.

page 130 (pdf 147):

-

Choosing stock

-

In the case of New Zealands, for example, blocky bucks and longer-bodied does will give you the meaty fryer-broilers you want to produce.

page 134 (pdf 151):

-

Inbreeding is the breeding of close relatives, such as brother and sister, mother and son, cousins, and so on.

-

Linebreeding is a form of inbreeding that follows a line of descent, usually from an outstanding ancestor, and involves the use of relatives such as grandmother and grandson, aunt and nephew, grandsire and granddaughter. Most successful rabbit breeders use a form of linebreeding. In other words, they inbreed on a line of descent from an outstanding rabbit or rabbits they feel will maintain good quality and improve their stock.

-

Outcrossing is the use of an unrelated animal of the same breed in the breeding program. Most breeders resort to an outcross at one time or another, no matter how much they would like to keep it in the family.

-

Crossbreeding is, of course, the mating of two different breeds. Some successful breeders of meat rabbits have raised pure strains of New Zealand Whites and Californians and then made judicious crosses to produce a hybrid fryer. Some angora wool producers have crossed different Angora breeds with good results. Generally speaking, however, crossbreeding is better left to the experts or those of an experimental turn of mind.

Part 3: Marketing and Miscellany

· Chapter 08: To the Best Market: Selling Rabbits

page 143 (pdf 160):

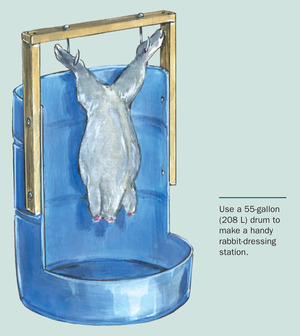

- 55 gallon abattoir:

page 144 (pdf 161):

- To kill the rabbit, hold it by the hind feet and quickly snap its head down and back, breaking the neck.

page 146 (pdf 163):

- After you’ve slaughtered the rabbit, run the carcass under cold running water like you would any cut of meat you might get from the supermarket. Then refrigerate the carcass (in plastic wrap or on a dish or tray) overnight or for at least a few hours before butchering. It is easier to make clean cuts in chilled meat.

· Chapter 09: Rabbits and the Home Garden

page 165 (pdf 182):

- Rabbit manure contains higher proportions of nitrogen and phosphorus than many other manures and more potash than most. It won’t burn plants or lawns even when applied fresh. It comes in a convenient round, dry form.

· Chapter 10: Preventing Problems

· Chapter 11: On to the Rabbit Shows

· Chapter 12: Rabbit Associations and the Future of the Industry

· Chapter 13: Cooking Rabbit

page 227 (pdf 210):

- American Rabbit Breeders Association. Official Guidebook, Raising Better Rabbits and Cavies. ARBA, 2000.