Home · Book Reports · 2022 · COVID-19: The Great Reset

- Author :: Klaus Schwab

- Publication Year :: 2020

- Read Date :: 2022-02-04

- Source :: covid-19_-the-great-reset-klaus-schwab.pdf

designates my notes. / designates important. / designates very important.

Thoughts

Inderdependence

One of, if not the, main points in this book is that of interdependence. We live in a hyper-connected world and complex world where ideas move so fast that we scarcely have time to understand them and even less chance of understanding their ramifications. The speed applies to the physical world with the just-in-time delivery system and in the financial world with its high-frequency trading much in the same way as it applies to ideas. The complexity part of the equation can be thought of as how many components in a given system touch other components in that system. When you have a high degree of coupling like this, it becomes very hard to make predictions and the system can respond intuitively, non-linearly, or exponentially when a simpler system responds predicatively linearly.

The covid-19 pandemic has forced a lot of the fragility in out world into the light.

This book contends that the challenges that must be overcome to ensure stability into the future will constitute what many have been calling the “new normal.” What this new normal looks like, and how it can be shaped, is the second aspect of this book.

One of the major changes we have seen is the use of lock downs. The question here is not whether the lock downs are effective, but how will people respond to the confinement? Will the pandemic lead to social unrest or will the policies put in place ostensibly to combat covid lead to unrest?

One outcome could be a docile response where people are more than willing to comply with any new policies, however unpalatable, in the name of safety. This seemed to be what we saw for most of 2021 and some of 2022. On the other hand covid could give rise to nationalism and retard globalization. This I think we have seen in the later part of 2022.

Whatever the response turns out to be, there is no denying that the world is' seeing the largest and fastest changes it has seen since the end of World War 2, and possible ever. Klaus compares the covid changes to women starting to work and vote, but he fails to mention how those seemingly minor changes precipitated a whole slew of societal changes. For example, once mom was out of the house, the children were being raised by then the television and now the internet. With mom in the workforce you diluted the labor market and brought down the price of a unit of labor. Now, mom and dad both must work to provide what a single earner could provide in the 70s and prior. These are good examples of how one change (women working) can have numerous downstream effects. (I have written about this more extensively in No History, No Family, No Future)

The post WW2 changes were sold as a way to raise the standard of living. Looking back we can see empirically that that has not been the case. Today the changes are being sold as a way to maintain safety. There are claims that covid is killing more people than the flu and that hospitals are being overloaded. To exacerbate these claims we have seen the “daily numbers” go from deaths “of” to deaths “with” to cases to suspected cases. It is of little surprise that each time we are presented with a new metric, the numbers get bigger. Clearly bigger numbers mean more danger, right?

So what are some of the changes that this book (and the media) are suggesting?

Big Brother

The number one measure in my opinion is the roll-out of a new global surveillance and tracking system. This takes a number of form, from the covid passport to smartphone (contact) tracking apps to pervasive facial recognition. All of this is being done, of course, to protect you and is only there to track covid, not you, right?.

allowing public-health officials to identify infected people very rapidly

Sadly, this will still be an easy sell since the media will tell us that tracking/tracing is for the greater good and will save lives. Then, any privacy laws that might have been in place to curtail this exact kind of thing (health record privacy laws for example) will be essentially ignored. The lockdowns forced regulators to relax because there was no other choice. (there was a choice, but the media framed it as life-and-death) We saw this in things like online learning, and e-medicine.

The honesty in regard to the degree of surveillance is actually a bit shocking:

it not only allows backtracking all the contacts with whom the user of a mobile phone has been in touch, but also tracking the user’s real-time movements, which in turn affords the possibility to better enforce a lockdown and to warn other mobile users in the proximity of the carrier that they have been exposed to someone infected.

Don’t worry though, we can trust the technology.

Margrethe Vestager, the EU Commissioner for Competition: I think it is essential that we show that we really mean it when we say that you should be able to trust technology when you use it, that this is not a start of a new era of surveillance.

See, we can trust the technology (my concern is with the people harnessing said technology) and that this is not, definitely not, for sure not, no-way no-how a “new era of surveillance”>

Trust is a four letter word to me, especially if we consider the increased surveillance after 9/11. The tracing/tracking apps and similar tech, once rolled out, will never be uninstalled.

Interestingly and unsurprisingly Mr. Schwab doesn’t spend a great deal of time looking at those kinds of changes. He hand waves them away as non-issues and while there is concern, it isn’t a big deal. He is more interested in the other class of major change we are already seeing, and I fear will be far more opaque to the average person than something as in-your-face as a phone app or surveillance camera.

The Great (Economic) Reset

“History shows that epidemics have been the great resetter of countries' economy and social fabric. Why should it be different with COVID-19?”

The real meat in regard to this “great reset” is economics. Klaus posits that the recovery will be slower for the pandemic than it would be for a war. He thinks that things will not be back to normal for at least 40 years! He thinks that in this uncertain time people will save more (good luck with all the inflation) and that labor will (somehow) do better than capital. Then he immediately changes his tune and says that labor won’t do better this time because of his expected covid driven surge in automation.

For the last 2 decades we have been hearing about automation being a job killer, but it really hasn’t come to fruition. Now though, with the advancements we have seen in machine learning (AI), this time I think automation is actually going to be a serious problem. While I think most people think robots when they hear automation, today I think the inroads will be in mid-level white collar jobs. Computers can now do things like legal research (a little worse than humans), interpret MRI-like scans (better than humans), and write trivial copy for newspapers (about the same as humans). With things like ChatGPT being trained by millions of curious people, it will improve very rapidly and we could easily see low level computer programming jobs and office/personal assistants replaced by it. Either way, my point is that automation is in my opinion a serious headwind I had previously dismissed.

When it comes to what really drives the economy, Klaus is spot on:

Because consumer sentiments are what really drive economies, a return to any kind of “normal” will only happen when and not before confidence returns.

This lull in consumer activity, which I argue is a good thing, will be used to as an opportunity to sell “degrowth”. You will “live better lives with less” and “you will own nothing and be happy.”

While Klaus flat out says “economic life cannot be activated by fiat” he then suggests all of the typical MMT (modern monetary theory) go-to fixes:

- cut intrest rates

- quantitative easing

- print the money to keep government functioning

- spend our way out, increase debt-to-GDP by as much as 33%

- moratorium on debts

- government as payer-of-last-resort

- whatever it takes

He then warns:

The artificial barrier that makes monetary and fiscal authorities independent from each other has now been dismantled, with central bankers becoming (to a relative degree) subservient to elected politicians.

Now that is some crazy talk. The money has always controlled the politics and that hasn’t changed one bit.

Then there is this gem:

One of the greatest concerns is that this implicit cooperation between fiscal and monetary policies leads to uncontrollable inflation. It originates in the idea that policy-makers will deploy massive fiscal stimulus that will be fully monetized, i.e. not financed through standard government debt. This is where Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and helicopter money come in: with interest rates hovering around zero, central banks cannot stimulate the economy by classic monetary tools; i.e. a reduction in interest rates – unless they decided to go for deeply negative interest rates, a problematic move resisted by most central banks.[49] The stimulus must therefore come from an increase in fiscal deficits (meaning that public expenditure will go up at a time when tax revenues decline). Put in the simplest possible (and, in this case, simplistic) terms, MMT runs like this: governments will issue some debt that the central bank will buy. If it never sells it back, it equates to monetary finance: the deficit is monetized (by the central bank purchasing the bonds that the government issues) and the government can use the money as it sees fit. It can, for example, metaphorically drop it from helicopters to those people in need. The idea is appealing and realizable, but it contains a major issue of social expectations and political control: once citizens realize that money can be found on a “magic money tree”, elected politicians will be under fierce and relentless public pressure to create more and more, which is when the issue of inflation kicks in.

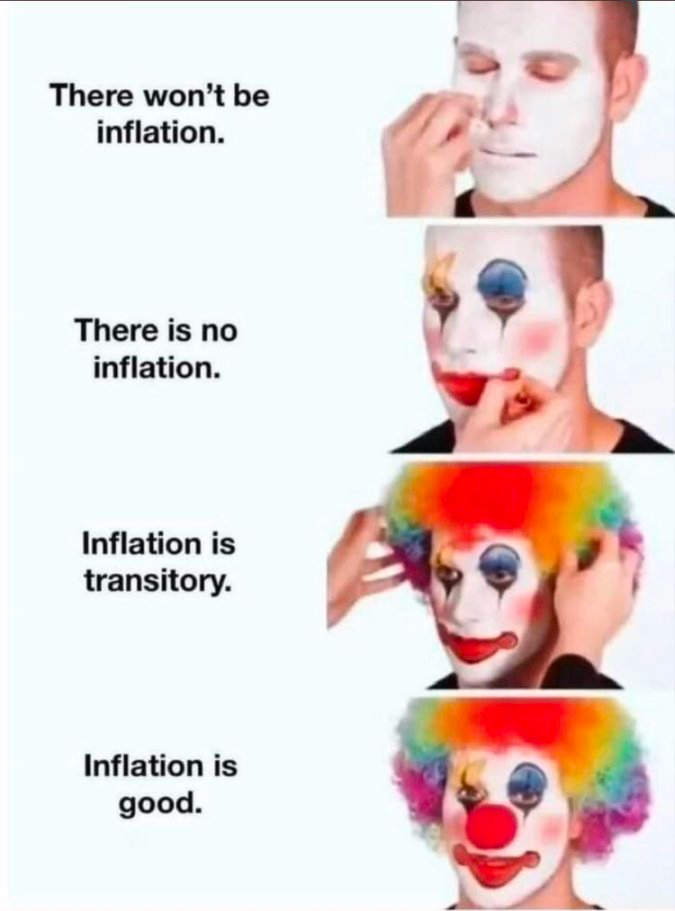

This is probably the most important point in this book and around covid in general. 2 years later (in early 2022) the inflation is here. It was not transitory. And I suspect people are going to shake the “magic money tree” again at some point. (which will only make things worse) And again I say, this all points to universal basic income.

Right after he literally calls for helicopter money, he says:

At this current juncture, it is hard to imagine how inflation could pick up anytime soon.

What?

And then in regard to pent-up demand caused by lockdowns:

When social distancing eventually eases, pent-up demand could provoke a bit of inflation, but it is likely to be temporary

Don’t worry, it is only going to be transitory!

Post WW2 redux

radical rethinking in the years following World War II, which included the establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions, the United Nations, the EU and the expansion of welfare states, shows the magnitude of the shifts possible.

Klaus goes on to talk about some of the things we might need to rethink:

- GDP

- The value of digital products

- Unpaid work (home-makers)

Another thing that needs rethinking, and this on I agree with, is that we currently count the shifting of financial assets around as some kind of growth that is included in GDP. While I am certainly not against the reward one receives in the form of interest when they loan money, there exists today a lack of risk in the sense that the central banks will simply bail out (or in) anyone in their in-group that fails. This is commonly refered to as social losses and privitize gains. Both of these examples (and there are many more) should be enough to exclude financial “gains” from GDP calculations.

At the core of the US dollar status as a reserve currency lies a critical issue of trust: non-Americans who hold dollars trust that the United States will protect both its own interests (by managing sensibly its economy) and the rest of the world as far as the US dollar is concerned (by managing sensibly its currency, like providing dollar liquidity to the global financial system efficiently and rapidly).

This is misplaced trust, at best. On the other hand it also demonstrates the current belief that the central bank (US Fed in this case) will make everyone whole. Further, this belief does not seem to take into account the next point the Klaus makes:

As for a global virtual currency, there is none in sight yet, but there are attempts to launch national digital currencies that may eventually dethrone the US dollar supremacy.

While he alludes to replacing the USD as world reserve currency with a digital currency, he conviniently leaves out several alternative that could also replace it: the yuan, gold, special drawing rights, or even some kind of commodity or commodity back currency.

Inequality (will only get worse)

Here again we see a contradiction.

the post-pandemic era will usher in a period of massive wealth redistribution, from the rich to the poor and from capital to labour.

I don’t even know what to say to this… Small businesses were crushed, people out of work, high CPI (which simultaniously hits the middle and lower classes that are living paycheck-to-paycheck while inflating the assets the upper class holds), and more automation in response to lockdown are only a few of the headwinds against this redistribution of wealth downward.

COVID-19 has exacerbated pre-existing conditions of inequality

He says this right after talking about wealth transfer from capital to labor.

Angus Deaton, the Nobel laureate who co-authored Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism with Anne Case, observed: “drug-makers and hospitals will be more powerful and wealthier than ever”,[59] to the disadvantage of the poorest segments of the population.

Again, how does this fit in the capital to labor weath transfer?

Bigger Brother

Rather than simply fixing market failures when they arise, [governments] should, as suggested by the economist Mariana Mazzucato: “move towards actively shaping and creating markets that deliver sustainable and inclusive growth. They should also ensure that partnerships with business involving government funds are driven by public interest, not profit”.[68]

This economist doesn’t mince their words: “actively shaping and creating markets”.

For decades, it [social contract] has slowly and almost imperceptibly evolved in a direction that forced individuals to assume greater responsibility for their individual lives and economic outcomes, leading large parts of the population (most evidently in the low- income brackets) to conclude that the social contract was at best being eroded, if not in some cases breaking down entirely.

This is a shortsighted view. Up until the advent of things like social security the individual, or rather the family, was dependent upon no one but themselves. Social security, pensions, and other forms of welfare are the historic exception rather than the rule. At best the past few decades are a return to the mean. This doesn’t mean it is not uncomfortable to the current generations that have grown up in the “welfare state”.

New World Order

Democracy and national sovereignty are only compatible if globalization is contained. By contrast, if both the nation state and globalization flourish, then democracy becomes untenable. And then, if both democracy and globalization expand, there is no place for the nation state. Therefore, one can only ever choose two out of the three – this is the essence of the trilemma.

See: the EU. “Globalized”/integrated economy and democracy leaves no place for the nation.

According to Wang Jisi, a renowned Chinese scholar and Dean of the School of International Studies at Peking University, the fallout from the pandemic has pushed China–US relations to their worst level since 1979, when formal ties were established. In his opinion, the bilateral economic and technological decoupling is “already irreversible”,[89] and it could go as far as the “global system breaking into two parts” warns Wang Huiyao, President of the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing.[90]

And why is this such a bad thing? 2 parallel systems would provide redundancy would they not? I am not saying it would be good, but I entertain the idea that is could be good. And what ever happened to diversity good?

The conspiracy theorist take might be that to build a world government, one must first construct regional governments. This now looks to be shaping up as the age-old east versus west, but I could see the Americas and Africa being sites for regional government along with Europe and Asia. I would expect India and Australia to fall in line with the east simply as a matter of location.

There isn’t a “right” view and a “wrong” view, but different and often diverging interpretations that frequently correlate with the origin, culture and personal history of those who profess them. Pursuing further the “quantum world” metaphor mentioned earlier, it could be inferred from quantum physic that objective reality does not exist. We think that observation and measurement define an “objective” opinion, but the micro-world of atoms and particles (like the macro-world of geopolitics) is governed by the strange rules of quantum mechanics in which two different observers are entitled to their own opinions (this is called a “superposition”: “particles can be in several places or states at once”).[92]

While this seems like Schwab is making the same argument I am (that a multi-polar world may be better), he is subtly injecting the concept of moral relativism and not so subtly rejecting objectivism.

In the words of [Niall] Ferguson: “The real lesson here is not that the U.S. is finished and China is going to be the dominant power of the 21st century. I think the reality is that all the superpowers – the United States, the People’s Republic of China and the European Union – have been exposed as highly dysfunctional."[100] Being big, as the proponents of this idea argue, entails diseconomies of scale: countries or empires have grown so large as to reach a threshold beyond which they cannot effectively govern themselves. This in turn is the reason why small economies like Singapore, Iceland, South Korea and Israel seem to have done better than the US in containing the pandemic and dealing with it.

The small countries in some cases did better with the pandemic, but others (Israel) did not. That said, I think the idea of diseconomies of scale is on point. Too big too fail is a blatant example of this. I am not sure how to square this idea with the potential rise of regional governments. I personally think more, smaller, nations that cooperate but are free to experiment with different forms of society would be best. Sadly, I think the WEF-types will push for more centralized control, much like what we have seen with the European Union.

Covid and Climate Change

At first glance, the pandemic and the environment might seem to be only distantly related cousins; but they are much closer and more intertwined than we think. Both have and will continue to interact in unpredictable and distinctive ways, ranging from the part played by diminished biodiversity in the behaviour of infectious diseases to the effect that COVID-19 might have on climate change

Covid reduced global CO2 by ~8%, not much at all considering how extensive lockdowns were. This tells me that people driving cars and industry in general are much less a contributor to CO2 “pollution” than we are told. That doens’t really matter though since the crisis cannot go to waste.

the COVID-19 crisis cannot go to waste and that now is the time to enact sustainable environmental policies.

and a few pages later, incase you missed it:

in effect, make “good use” of the pandemic by not letting the crisis go to waste.

In regard to economy being more important than climate change in post-covid recovery era:

Low oil prices (if sustained, which is likely) could encourage both consumers and businesses to rely even more on carbon-intensive energy.

Klaus gets another one wrong. This oil price increase has been blamed on Russia, but the real culprit is the printing and injecting trillions of dollars into the economy.

Our consumption patterns changed dramatically during the lockdowns by forcing us to focus on the essential and giving us no choice but to adopt “greener living”.

Here we go again with “forcing” the “greener living” on everyone.

The Micro Reset

Micro reset is literally the title of the second half of the book. By micro though, Klaus means industries and companies. I guess that is micro if your macro is global governments. What we he call home economics?

“online” should be the largest beneficiary of the pandemic

“just-in-case” will eventually replace “just-in-time”

Small businesses are the main engine of employment growth and account in most advanced economies for half of all private-sector jobs. If significant numbers of them go to the wall, if there are fewer shops, restaurants and bars in a particular neighbourhood, the whole community will be impacted as unemployment rises and demand dries up, setting in motion a vicious and downward spiral and affecting ever greater numbers of small businesses in a particular community. The ripples will eventually spread beyond the confines of the local community,

Interestingly enough, this is basically what I want via a general boycott. Painful? Yes. Although I see no way out of the consumer-driven money-over-everything world we live in. Sadly I suspect that if this “downward spiral” was not chosen willingly (as with a boycott), the people would likely clamor for the government to step in and save them. I could see this as the final phase in getting the people to accept universal basic income.

big businesses will get bigger while the smallest shrink or disappear.

The bigger the business the more likely they can weather the storm. Additionally, the bigger the business the more likely they will have a seat at the free money trough we call the Federal Reserve.

During the lockdowns, a lot of consumers were forced to learn to do things for themselves (bake their bread, cook from scratch, cut their own hair, etc.) and felt the need to spend cautiously. How entrenched will these new habits and forms of “do it yourself” and auto-consumption become in the post-pandemic era? The same could apply to students who in trimester spent watching their professors on their screens, will they start questioning the high cost of education?

This is, in my opinion, the best effect that the pandemic has had. Anytime people learn that they can do it themselves they gain a bit more independence.

The combination of AI, the IoT and sensors and wearable technology will produce new insights into personal well-being. They will monitor how we are and feel, and will progressively blur the boundaries between public healthcare systems and personalized health creation systems – a distinction that will eventually break down. Streams of data in many separate domains ranging from our environments to our personal conditions will give us much greater control over our own health and well-being.

Here “us” is supposed to be you and I, but in typical misleading language, Klaus really means us as in he and his fellow oligarchs will have greater control. Similar to “YOU will own nothing and be happy” instead of “WE…”.

In banking, it is about being prepared for the digital transformation. In insurance, it is about being prepared for the litigations that are coming. In automotive, it is about being prepared for the coming shortening of supply chains. In the electricity sector, it is about being prepared for the inevitable energy transition.

Central bank digital currency, obviously, is the digital transformation in banking. As for the litigations in insurance, is he alluding to lawsuits for improtper treatment of covid (no Ivermectin, no early treatment, wait and see approach)? The automotive shorting supply chains seems reasonable (as I assume we will see more supply chain shortening across the board where applicaable. Finally the energy transition I think is total bullshit. Look at how Europe is doing right now without Russian gas.

And for one more time, incase you missed it the first two times (and the countless other implicatins):

Those that adapt with agility and imagination will eventually turn the COVID-19 crisis to their advantage.

Get Used to It

“Jin Qi (one of China’s leading scientists) had it right when he said in April 2020: “This is very likely to be an epidemic that co- exists with humans for a long time, becomes seasonal and is sustained within human bodies."[19]”

We have already seen that in the 2022-2023 winter. There has been a push to scare people with the “triple-demic” of flu/RSV/covid. From what I can see locally, the people aren’t buying it.

Table of Contents

- About Covid-19: The Great Reset

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: MACRO RESET

- 1.1. Conceptual framework – Three defining

- 1.2. Economic reset

- 1.3 Societal Reset

- 1.4. Geopolitical reset

- 1.5. Environmental reset

- 1.6. Technological reset

- Chapter 2. MICRO RESET (INDUSTRY AND BUSINESS)

- 2.1. Micro trends

- 2.2. Industry reset

- Chapter 3. INDIVIDUAL RESET

- 3.1. Redefining our humanness

About Covid-19: The Great Reset

page 3 (pdf 4):

-

The book’s main objective is to help understand what’s coming in a multitude of domains. Published in July 2020, in the midst of the crisis…

-

The first assesses what the impact of the pandemic will be on five key macro categories: the economic, societal, geopolitical, environmental and technological factors. The second considers the effects in micro terms, on specific industries and companies. The third hypothesizes about the nature of the possible consequences at the individual level.

Introduction

page 11 (pdf 12):

-

we will be dealing with its [Covid] fallout for years

-

A new world will emerge, the contours of which are for us to both imagine and to draw.

when things will return to normal. The short response is: never.

page 12 (ped 13):

- will shape a “new normal” radically different from the one we will be progressively leaving behind. Many of our beliefs and assumptions about what the world could or should look like will be shattered in the process.

page 13 (pdf 14):

-

there is nothing new about the confinement and lockdowns imposed upon much of the world to manage COVID-19. They have been common practice for centuries. The earliest forms of confinement came with the quarantines instituted in an effort to contain the Black Death that between 1347 and 1351 killed about a third of all Europeans.

-

A little difference in numbers of deaths means nothing?

-

authorities that try to keep us safe by enforcing confinement measures are often perceived as agents of oppression.

-

In medieval Europe, the Jews were almost always among the victims of the most notorious pogroms provoked by the plague. One tragic example illustrates this point: in 1349, two years after the Black Death had started to rove across the continent, in Strasbourg on Valentine’s day, Jews, who’d been accused of spreading the plague by polluting the wells of the city, were asked to convert. About 1,000 refused and were burned alive.

-

I am actually quite surprised that they work Jews in. Interestingly the “accused of spreading plague” is not fleshed out. Was it true? Was there anyone (Jew or otherwise) doing this? The accusation is presented here as totally fanciful. Who knows…

page 14 (pdf 15):

-

pandemic is dramatically exacerbating pre-existing dangers that we’ve failed to confront adequately for too long.

-

Is the pandemic like the Spanish flu of 1918 (estimated to have killed more than 50 million people worldwide in three successive waves)? Could it look like the Great Depression that started in 1929? Is there any resemblance with the psychological shock inflicted by 9/11? Are there similarities with what happened with SARS in 2003 and H1N1 in 2009 (albeit on a different scale)? Could it be like the great financial crisis of 2008, but much bigger? The correct, albeit unwelcome, answer to all of these is: no! None fits the reach and pattern of the human suffering and economic destruction caused by the current pandemic.

-

Wait, what?! 50 million dead to Spanish flu doesn’t fit the “human suffering and economic destruction” of covid?

-

Interesting we rehash both the Great Depression and 2008 GFC as well as the always emotional (never forget!) 9/11.

page 15 (pdf 16):

-

The economic fallout in particular bears no resemblance to any crisis in modern history. As pointed out by many heads of state and government in the midst of the pandemic, we are at war, but with an enemy that is invisible, and of course metaphorically: “If what we are going through can indeed be called a war, it is certainly not a typical one. After all, today’s enemy is shared by all of humankind”.[3]

-

Like communism? Or Terrorists? Or Drugs? Or Poverty? Or the countless other invisible boogie men we are/were at “war” with?

-

World War 2 is the closest mental anchor.

-

World War II was the quintessential transformational war, triggering not only fundamental changes to the global order and the global economy, but also entailing radical shifts in social attitudes and beliefs that eventually paved the way for radically new policies and social contract provisions (like women joining the workforce before becoming voters).

-

WW2 was when cybernetics/general systems theory was applied to propaganda. Everything before had to be destroyed to build what the globalists/oligarchs are “build back bettering” right now. Women vote and enter the workforce (not taxation without representation) leads directly to the decline of the family. With fewer homemakers (not house wives) children are left to media to raise themselves. With these women entering the labor market wages were depressed for everyone else (simple supply/demand). Now-a-days mom and dad both work to afford 1 or 2 children. Pre WW2 dad would be able to afford a stay at home mom and 2-3 children (that actually were raised by mom).

-

If Klaus sees Covid as WW2 2.0, I weep for the future.

page 16 (pdf 17):

-

At the very least, as we will argue, the pandemic will accelerate systemic changes that were already apparent prior to the crisis: the partial retreat from globalization, the growing decoupling between the US and China, the acceleration of automation, concerns about heightened surveillance, the growing appeal of well-being policies, rising nationalism and the subsequent fear of immigration, the growing power of tech, the necessity for firms to have an even stronger online presence, among many others.

-

If this is half true, all hail Covid, savior of the

worldnation! -

It might thus provoke changes that would have seemed inconceivable before the pandemic struck, such as new forms of monetary policy like helicopter money (already a given)

page 17 (pdf 18):

-

we should take advantage of this unprecedented opportunity to reimagine our world, in a bid to make it a better and more resilient one as it emerges on the other side of this crisis.

-

Better is subjective. Klaus’ vision of a better world and mine are probably very different.

-

our objective was to write a relatively concise and simple book to help the reader understand what’s coming in a multitude of domains.

-

Does Klaus have a crystal ball? He knows what is coming?

Chapter 1: MACRO RESET

1.1. Conceptual framework – Three defining

page 19 (pdf 20):

-

characteristics of today’s world The macro reset will occur in the context of the three prevailing secular forces that shape our world today: interdependence, velocity and complexity.

-

“hyperconnected”

-

the world is “concatenated”: linked together.

-

In the early 2010s, Kishore Mahbubani, an academic and former diplomat from Singapore, captured this reality with a boat metaphor: “The 7 billion people who inhabit planet earth no longer live in more than one hundred separate boats [countries]. Instead, they all live in 193 separate cabins on the same boat.”

-

Global village.

-

In 2020, he pursued this metaphor further in the context of the pandemic by writing: “If we 7.5 billion people are now stuck together on a virus-infected cruise ship, does it make sense to clean and scrub only our personal cabins while ignoring the corridors and air wells outside, through which the virus travels? The answer is clearly: no. Yet, this is what we have been doing. … Since we are now in the same boat, humanity has to take care of the global boat as a whole”.[5]

page 20 (pdf 21):

-

We can all think of economic risks turning into political ones (like a sharp rise in unemployment leading to pockets of social unrest), or of technological risks mutating into societal ones (such as the issue of tracing the pandemic on mobile phones provoking a societal backlash).

-

Such concern of social unrest/backlash. Could it be because those things rock the “boat” in which Mr. Schwab has a first class cabin and the ear of the captain?

page 22 pdf (23):

-

In the past, this “silo thinking” partly explains why so many economists failed to predict the credit crisis (in 2008) and why so few political scientists saw the Arab Spring coming (in 2011). Today, the problem is the same with the pandemic.

-

Except many people saw 2008 coming (not sure about Arab Spring) and Event 201 was almost prophetic in predicting COVID. Not to mention, Event 201 was very interdisciplinary.

page 25 (pdf 24):

-

Ernest Hemingway understood this. In his novel The Sun Also Rises, two characters have the following conversation: “How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked. “Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually, then suddenly.” The same tends to happen for big systemic shifts and disruption in general: things tend to change gradually at first and then all at once. Expect the same for the macro reset.

-

Referencing the inability for people to understand exponential rates.

-

Let’s take the example of the US to hammer out the point and better grasp the role played by velocity in all of this. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), between 39 and 56 million Americans contracted the flu during the 2019-2020 winter season, with between 24,000 and 62,000 deaths.[9] By contrast, and according to Johns Hopkins University, on 24 June 2020, more than 2.3 million were diagnosed with COVID-19 and almost 121,000 people had died.[10] But the comparison stops there; it is meaningless for two reasons: 1) the flu numbers correspond to the estimated total flu burden while the COVID-19 figures are confirmed cases; and 2) the seasonal flu cascades in “gentle” waves over a period of (up to six) months in an even pattern while the COVID-19 virus spreads like a tsunami in a hotspot pattern (in a handful of cities and regions where it concentrates) and, in doing so, can overwhelm and jam healthcare capacities

-

In hindsight we can see he is wrong. The hospitals were not overwhelmed and the “confirmed” cases were confirmed by the now understood to be erroneous test. And, if people aren’t overwhelming hospitals or dieing, why does it matter how many cases there are? Unless you simply want a bigger number to scare people with.

page 28 (pdf 27):

- the containment of the coronavirus pandemic will necessitate a global surveillance network capable of identifying new outbreaks as soon as they arise

page 28 (pdf 29):

- However, we can confidently assert that the pandemic (a high probability, high consequences white-swan event) will provoke many black-swan events through second-, third-, fourth- and more-order effects.

1.2. Economic reset

page 31 (pdf 32):

-

History shows that epidemics have been the great resetter of countries’ economy and social fabric. Why should it be different with COVID-19?

-

A seminal paper on the long-term economic consequences of major pandemics throughout history shows that significant macroeconomic after-effects can persist for as long as 40 years, substantially depressing real rates of return.[18] This is in contrast to wars that have the opposite effect: they destroy capital while pandemics do not – wars trigger higher real interest rates, implying greater economic activity, while pandemics trigger lower real rates, implying sluggish economic activity. In addition, consumers tend to react to the shock by increasing their savings,

-

Don’t worry, since everything is so much faster, that 40 years will be reduced to a week and a half.

-

Or maybe we can just start a war, they are much more economically conducive.

-

On the labour side, there will be gains at the expense of capital since real wages tend to rise after pandemics.

page 32 (pdf 33):

-

labour gains in power to the detriment of capital. Nowadays, this phenomenon may be exacerbated by the ageing of much of the population around the world (Africa and India are notable exceptions), but such a scenario today risks being radically altered by the rise of automation

-

Nope, sorry slaves. In all his historical examples labor benefits at the expense of capital… except this time because of automation.

-

Jin Qi (one of China’s leading scientists) had it right when he said in April 2020: “This is very likely to be an epidemic that co- exists with humans for a long time, becomes seasonal and is sustained within human bodies."[19]

page 33 (pdf 34):

-

These three plausible scenarios[22] are all based on the core assumption that the pandemic could go on affecting us until 2022

-

This was written in 2020. How could anyone predict “until 2022”?

page 35 (pdf 36):

-

Because consumer sentiments are what really drive economies, a return to any kind of “normal” will only happen when and not before confidence returns.

-

governments must do whatever it takes and spend whatever it costs in the interests of our health and our collective wealth for the economy to recover sustainably.

page 36 (pdf 37):

-

“If governments fail to save lives, people afraid of the virus will not resume shopping, traveling, or dining out. This will hinder economic recovery, lockdown or no lockdown.”

-

This is not at all how it played out in places like TX and FL.

-

economic life cannot be activated by fiat

page 39 (pdf 40):

-

The next hurdle is the political challenge of vaccinating enough people worldwide (we are collectively as strong as the weakest link) with a high enough compliance ratedespite the rise of anti-vaxxers.

-

Why are we only as strong as out weakest link? If someone, for whatever reason, dies of covid, how does that hurt anyone else economically? If the so-called vaccines work and those that don’t take them die off, who cares?

page 45 (pdf 46):

- The deep disruption caused by COVID-19 globally has offered societies an enforced pause to reflect on what is truly of value. With the economic emergency responses to the pandemic now in place, the opportunity can be seized to make the kind of institutional changes and policy choices that will put economies on a new path towards a fairer, greener future. The history of radical rethinking in the years following World War II, which included the establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions, the United Nations, the EU and the expansion of welfare states, shows the magnitude of the shifts possible.

page 46 (pdf 47):

-

GDP itself needs to be updated to reflect the value created in the digital economy, the value created through unpaid work as well as the value potentially destroyed through certain types of economic activity. The omission of value created through work carried out in the household has been a long-standing issue

-

Value of home-making; something I actually agree with!

-

certain types of financial products, which through their inclusion in GDP are captured as value creating, are merely shifting value from one place to another

-

Wow, I agree again.

page 47 (pdf 48):

-

in 2019, a country placed in the top 10 ranking of the World Happiness Report unveiled a “well-being budget”. The Prime Minster of New Zealand’s decision to earmark money for social issues, such as mental health, child poverty and family violence, made well-being an explicit goal of public policy.

-

Universal basic income?

page 50 (pdf 51):

-

By triggering a period of enforced degrowth, the pandemic has spurred renewed interest in this movement that wants to reverse the pace of economic growth, leading more than 1,100 experts from around the world to release a manifesto in May 2020 putting forward a degrowth strategy to tackle the economic and human crisis caused by COVID-19.[43] Their open letter calls for the adoption of a democratically “planned yet adaptive, sustainable, and equitable downscaling of the economy, leading to a future where we can live better with less”.

-

You will own nothing and be happy.

-

central banks decided almost immediately after the beginning of the outbreak to cut interest rates while launching large quantitative-easing programmes, committing to print the money necessary to keep the costs of government borrowing low. The US Fed undertook to buy Treasury bonds and agency mortgage-backed securities, while the European Central Bank promised to buy any instrument that governments would issue (a move that succeeded in reducing the spread in borrowing costs between weaker and stronger eurozone members).

page 51 (pdf 52):

-

fight the pandemic with as much spending as required

-

These measures will lead to very large fiscal deficits, with a likely increase in debt-to-GDP ratios of 30% of GDP in the rich economies.

-

High-income countries have more fiscal space because a higher level of debt should prove sustainable and entail a viable level of welfare cost for future generations, for two reasons: 1) the commitment from central banks to purchase whatever amount of bonds it takes to maintain low interest rates; and 2) the confidence that interest rates are likely to remain low in the foreseeable future because uncertainty will continue hampering private investment and will justify high levels of precautionary savings.

-

At least he is being honest.

page 52 (pdf 53):

-

help [for lower GDP countries] in the form of grants and debt relief, and possibly an outright moratorium,[46] will not only be needed but will be critical.

-

Carmen Reinhart has called it a “whatever-it-takes moment for large-scale, outside- the-box fiscal and monetary policies”.[47]

-

Measures that would have seemed inconceivable prior to the pandemic may well become standard around the world as governments try to prevent the economic recession from turning into a catastrophic depression. Increasingly, there will be calls for government to act as a “payer of last resort”[48] to prevent or stem the spate of mass layoffs and business destruction triggered by the pandemic.

-

But how can governments actually be this payer of last resort? Thier only “income” is via taxation. So, at best, government can redistribute current or future taxes to current populations. Is this not wealth redistribution? Universal basic income?

-

The artificial barrier that makes monetary and fiscal authorities independent from each other has now been dismantled, with central bankers becoming (to a relative degree) subservient to elected politicians.

-

Now that is some crazy talk. The money has always controlled the politics and that hasn’t changed one bit.

-

the precept that government can intervene to preserve workers’ jobs or incomes and protect companies from bankruptcy may endure after these policies come to an end. It is likely that public and political pressure to maintain such schemes will persist, even when the situation improves.

-

I know I keep saying it, but… universal basic income.

page 53 (pdf 54):

-

One of the greatest concerns is that this implicit cooperation between fiscal and monetary policies leads to uncontrollable inflation. It originates in the idea that policy-makers will deploy massive fiscal stimulus that will be fully monetized, i.e. not financed through standard government debt. This is where Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and helicopter money come in: with interest rates hovering around zero, central banks cannot stimulate the economy by classic monetary tools; i.e. a reduction in interest rates – unless they decided to go for deeply negative interest rates, a problematic move resisted by most central banks.[49] The stimulus must therefore come from an increase in fiscal deficits (meaning that public expenditure will go up at a time when tax revenues decline). Put in the simplest possible (and, in this case, simplistic) terms, MMT runs like this: governments will issue some debt that the central bank will buy. If it never sells it back, it equates to monetary finance: the deficit is monetized (by the central bank purchasing the bonds that the government issues) and the government can use the money as it sees fit. It can, for example, metaphorically drop it from helicopters to those people in need. The idea is appealing and realizable, but it contains a major issue of social expectations and political control: once citizens realize that money can be found on a “magic money tree”, elected politicians will be under fierce and relentless public pressure to create more and more, which is when the issue of inflation kicks in.

-

This is probably the most important point in this book and around covid in general. 2 years later (in early 2022) the inflation is here. It was not transitory. And I suspect people are going to shake the “magic money tree” again at some point. (which will only make things worse) And again I say, this all points to universal basic income.

-

Central bankers may decide that there is nothing to worry about with inflation at 2% or 3%, and that 4% to 5% is also fine, but they will have to define an upper limit at which inflation becomes disruptive

page 54 (pdf 55):

-

At this current juncture, it is hard to imagine how inflation could pick up anytime soon.

-

What?

-

When social distancing eventually eases, pent-up demand could provoke a bit of inflation, but it is likely to be temporary

-

Transitory!

page 56 (pdf 57):

-

At the core of the US dollar status as a reserve currency lies a critical issue of trust: non-Americans who hold dollars trust that the United States will protect both its own interests (by managing sensibly its economy) and the rest of the world as far as the US dollar is concerned (by managing sensibly its currency, like providing dollar liquidity to the global financial system efficiently and rapidly).

-

This is misplaced trust, at best.

page 57 (pdf 58):

-

As for a global virtual currency, there is none in sight yet, but there are attempts to launch national digital currencies that may eventually dethrone the US dollar supremacy.

-

To replace the USD as world reserve.

1.3 Societal Reset

page 59 (pdf 60):

- Henry Kissinger observed: “Nations cohere and flourish on the belief that their institutions can foresee calamity, arrest its impact and restore stability. When the COVID-19 pandemic is over, many countries’ institutions will be perceived as having failed”.[55]

page 60 (pdf 61):

-

the post-pandemic era will usher in a period of massive wealth redistribution, from the rich to the poor and from capital to labour.

-

I don’t even know what to say to this… Small businesses crushed, people out of work, high inflation, more automation, etc.

page 61 (pdf 62):

-

COVID-19 has exacerbated pre-existing conditions of inequality

-

He says this right after talking about wealth transfer from capital to labor.

page 64 (pdf 65):

-

Angus Deaton, the Nobel laureate who co-authored Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism with Anne Case, observed: “drug-makers and hospitals will be more powerful and wealthier than ever”,[59] to the disadvantage of the poorest segments of the population.

-

Again, how does this fit in the capital to labor weath transfer?

page 66 (pdf 67):

- Jacob Wallenberg, the Swedish industrialist, is one of them. In March 2020, he wrote: “If the crisis goes on for long, unemployment could hit 20-30 per cent while economies could contract by 20-30 per cent … There will be no recovery. There will be social unrest. There will be violence. There will be socio- economic consequences: dramatic unemployment. Citizens will suffer dramatically: some will die, others will feel awful."[62]

page 68 (pdf 69):

-

In the words of John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge: “The COVID-19 pandemic has made government important again. Not just powerful again (look at those once-mighty companies begging for help), but also vital again: It matters enormously whether your country has a good health service, competent bureaucrats and sound finances. Good government is the difference between living and dying”.[65]

-

If a population can take care of itself, the government has little impact. As for those “mighty” corporations; all the ever did was use government to create favorable legislation (i.e. artificial barriers to entry) and bailouts.

page 71 (pdf 70):

-

acute crises contribute to boosting the power of the state.

-

France’s top rate of income tax was zero in 1914; a year after the end of World War I, it was 50%. Canada introduced income tax in 1917 as a “temporary” measure to finance the war, and then expanded it dramatically during World War II with a flat 20% surtax imposed on all income tax payable by persons other than corporations and the introduction of high marginal tax rates (69%).

-

Similarly, during World War II, income tax in America turned from a “class tax” to a “mass tax”, with the number of payers rising from 7 million in 1940 to 42 million in 1945. The most progressive tax years in US history were 1944 and 1945, with a 94% rate applied to any income above $200,000 (the equivalent in 2009 of $2.4 million). Such top rates, often denounced as confiscatory by those who had to pay them, would not drop below 80% for another 20 years.

-

In the UK during the war, the top income tax rate rose to an extraordinarily stunning 99.25%![67]

page 71 (pdf 72):

-

Rather than simply fixing market failures when they arise, [governments] should, as suggested by the economist Mariana Mazzucato: “move towards actively shaping and creating markets that deliver sustainable and inclusive growth. They should also ensure that partnerships with business involving government funds are driven by public interest, not profit”.[68]

-

governments will most likely, but with different degrees of intensity, decide that it’s in the best interest of society to rewrite some of the rules of the game and permanently increase their role.

page 73 (pdf 74):

-

Joseph Stiglitz: “The first priority is to (…) provide more funding for the public sector, especially for those parts of it that are designed to protect against the multitude of risks that a complex society faces, and to fund the advances in science and higher-quality education, on which our future prosperity depends. These are areas in which productive jobs – researchers, teachers, and those who help run the institutions that support them – can be created quickly. Even as we emerge from this crisis, we should be aware that some other crisis surely lurks around the corner. We can’t predict what the next one will look like – other than it will look different from the last.[69]”

-

Looks like Joe and I have a disagreement on “productive”. Not to say the jobs he listed are worthless, but they don’t technically produce anything.

page 73 (pdf 74:

-

For decades, it [social contract] has slowly and almost imperceptibly evolved in a direction that forced individuals to assume greater responsibility for their individual lives and economic outcomes, leading large parts of the population (most evidently in the low- income brackets) to conclude that the social contract was at best being eroded, if not in some cases breaking down entirely.

-

This is a shortsighted view. Up until the advent of things like social security the individual, or rather the family, was dependent upon no one but themselves. Social security, pensions, and other forms of welfare are the historic exception rather than the rule. At best the past few decades are a return to the mean. This doesn’t mean it is not uncomfortable to the current generations that have grown up in the “welfare state”.

page 74 (pdf 75):

-

The apparent illusion of low or no inflation is a practical and illustrative example of how this erosion plays out in real-life terms. For many years the world over, the rate of inflation has fallen for many goods and services, with the exception of the three things that matter the most to a great majority of us: housing, healthcare and education. For all three, prices have risen sharply, absorbing an ever-larger proportion of disposable incomes and, in some countries, even forcing families to go into debt to receive medical treatment. Similarly, in the pre-pandemic era, work opportunities had expanded in many countries, but the increase in employment rates often coincided with income stagnation and work polarization.

-

Inflation in just about everything (food being a major one Klaus neglects to mention) except electronic distractions.

-

Increase employment rates happened when (in western nations at least) women entered the workforce. It should be no suprise that when you expand the supply (of labor) it will drive prices (wages) down. This is seen clearly in the now normal 2-income family that has, at best, retained the lifestyle of a single-income family from 2 generations ago. Remove the mothers from the home and placing them in the workplace has also impacted each subsequent generation that now is predominatly raised by teachers (nothing more than day-care at this point) and media (TV, then internet, now social).

page 75 (pdf 76):

-

A broader, if not universal, provision of social assistance, social insurance, healthcare and basic quality services

-

A move towards enhanced protection for workers and for those currently most vulnerable (like those employed in and fuelling the gig economy in which full-time employees are replaced by independent contractors and freelancers).

-

Foundations for the new social contract. These, while they might sound nice, feel like making people more reliant on daddy government to take care of them. Obviously completely unregulated capitalism tends to facism and complete socialism leads to communism (both basically the same ala F.A. Hayek’s horseshoe theory - corporations or the party with the power over the masses) a combination of social saftey nets and a true free market is probably the best solution.

-

In countries that were perceived as providing a sub-par response to the pandemic, many citizens will start asking critical questions such as: Why is it that in the midst of the pandemic, my country often lacked masks, respirators and ventilators? Why wasn’t it properly prepared? Does it have to do with the obsession with short-termism? Why are we so rich in GDP terms and so ineffective at delivering good healthcare to all those who need it? How can it be that a person who has spent more than 10 years’ training to become a medical doctor and whose end-of-year “results” are measured in lives receives compensation that is meagre compared to that of a trader or a hedge fund manager?

-

My first question would not be why was my country not prepared, but why was “I” not prepared. There were plenty of “preppers” that weathered the storm quite well. Why does society ridicule the most prepared among us?

-

When it comes to why do doctors earn less than hedge fund managers, the answer is pretty simple: you don’t care about a doctor until you need one while everyone wants more money all the time. People funnel billions of dollars a year into the hands of traders expecting a return. If they cared more about healthcare they would, ostensibly, redirect some of that money there. As I said though, no one cares about health care until they need it.

page 77 (pdf 78):

-

There is currently growing concern that the fight against this pandemic and future ones will lead to the creation of permanent surveillance societies. This issue is explored in more detail in the chapter on the technological reset, but suffice to say that a state emergency can only be justified when a threat is public, universal and existential.

-

Future pandemics will lead to (increased) surveillance societies.

page 78 (pdf 79):

-

The young generation is firmly at the vanguard of social change. There is little doubt that it will be the catalyst for change and a source of critical momentum for the Great Reset.

-

There is more to it than Klaus leads you to believe. Surely the system is broken and the younger generation sees it, but they have also been radicalized by a (hyper) progressive education system.

1.4. Geopolitical reset

page 79 (pdf 80):

-

the chaotic end of multilateralism, a vacuum of global governance and the rise of various forms of nationalism[76] make it more difficult to deal with the outbreak.

-

Meaning the world is moving to unilateralism? While nationalism is on the rise, I don’t think that is necessarily the end of multilateralism. Nations can put themselves first but still work with other nations. [[Jefferson, Thomas]] said “Commerce with all nations, alliance with none, should be our motto."

-

The late economist Jean-Pierre Lehmann (who taught at IMD in Lausanne) summed up today’s situation with great perspicacity when he said: “There is no new global order, just a chaotic transition to uncertainty." More recently, Kevin Rudd, President of the Asia Society Policy Institute and former Australian Prime Minister, expressed similar sentiments, worrying specifically about the “coming post-COVID-19 anarchy”: “Various forms of rampant nationalism are taking the place of order and cooperation. …"

-

Again this is silly. Nations should do what is best for themselves but that isn’t mutually exclusive to working together. The joke is that the same people calling for “diversity” actually want homogeneity - a one world government.

page 80 (pdf 81):

- If no one power can enforce order, our world will suffer from a “global order deficit”.

page 81 (pdf 82):

-

The global trade talks that started in the early 2000s failed to deliver an agreement, while during that same period the political and societal backlash against globalization relentlessly gained strength.

-

Maybe I’m naive, but “trade talks” (assume this is things like NAFTA and the TPP) seem pretty well overkill to me. Wouldn’t it be more reasonable, if not more cumbersome, to negotiate on a per (block) trade basis? Why this need to permanent regulations? It seems like the complete opposite of free trade.

-

The global economy is so intricately intertwined that it is impossible to bring globalization to an end. However, it is possible to slow it down and even to put it into reverse.

-

Stated so matter-of-factly. If it can be reversed, eventually it would be ended. Not that I suggest ending it, but it has had fairly disasterous results.

page 82 (pdf 83):

-

Democracy and national sovereignty are only compatible if globalization is contained. By contrast, if both the nation state and globalization flourish, then democracy becomes untenable. And then, if both democracy and globalization expand, there is no place for the nation state. Therefore, one can only ever choose two out of the three – this is the essence of the trilemma.

-

See: the EU. “Globalized”/integrated economy and democracy leaves no place for the nation.

page 83 (pdf 84):

-

regionalization may well become a new watered-down version of globalization

-

Examples: EU and ASEAN.

page 86 (pdf 87):

-

A hasty retreat from globalization would entail trade and currency wars, damaging every country’s economy, provoking social havoc and triggering ethno- or clan nationalism.

-

If every country’s economy is damaged (or benefited) isn’t the net result 0? Of course there would likely be winner and losers, but it is kind of like that saying: a rising (or sinking) tide lifts all ships. We can see this every day when currency pairs on Forex don’t really change even though both nations might be printing. If the print in balance, there is no change in the exchange rate.

-

This will only come about through improved global governance – the most “natural” and effective mitigating factor against protectionist tendencies.

-

If we do not improve the functioning and legitimacy of our global institutions, the world will soon become unmanageable and very dangerous. There cannot be a lasting recovery without a global strategic framework of governance.

-

Says Mr. Global.

page 89 (pdf 90):

-

In the case of the pandemic, in contrast with other recent global crises like 9/11 or the financial crisis of 2008, the global governance system failed, proving either non-existent or dysfunctional.

-

How was 9/11 a global crisis? And what was the global response? I suppose the ramping up of “terrorism”, but that was more of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

page 90 (pdf 91):

-

it is inconceivable that the global economy could “restart” without sustained international cooperation.

-

Why? Nations will come back online as they see fit, trade will resume in time, and eventually the global economy will be back online. I would assume nations will try to be more internally sufficient and that may lead to a loss of some global trade, but a strengthening of internal economies (albeit at a likely higher cost to consumers).

-

In the post-pandemic era, COVID-19 might be remembered as the turning point that ushered in a “new type of cold war”[88] between China and the US (the two words “new type” matter considerably: unlike the Soviet Union, China is not seeking to impose its ideology around the world).

page 91 (pdf 92):

-

According to Wang Jisi, a renowned Chinese scholar and Dean of the School of International Studies at Peking University, the fallout from the pandemic has pushed China–US relations to their worst level since 1979, when formal ties were established. In his opinion, the bilateral economic and technological decoupling is “already irreversible”,[89] and it could go as far as the “global system breaking into two parts” warns Wang Huiyao, President of the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing.[90]

-

And why is this such a bad thing? 2 parallel systems would provide redundancy would they not? I am not saying it would be good, but I entertain the idea that is could be good. And what ever happened to diversity is good?

-

There isn’t a “right” view and a “wrong” view, but different and often diverging interpretations that frequently correlate with the origin, culture and personal history of those who profess them. Pursuing further the “quantum world” metaphor mentioned earlier, it could be inferred from quantum physic that objective reality does not exist. We think that observation and measurement define an “objective” opinion, but the micro-world of atoms and particles (like the macro-world of geopolitics) is governed by the strange rules of quantum mechanics in which two different observers are entitled to their own opinions (this is called a “superposition”: “particles can be in several places or states at once”).[92]

-

While this seems like Schwab is making the same argument I am, he is subtly injecting the concept of moral relativism and not so subtly rejecting objectivism.

page 96 (97):

-

In the words of [Niall] Ferguson: “The real lesson here is not that the U.S. is finished and China is going to be the dominant power of the 21st century. I think the reality is that all the superpowers – the United States, the People’s Republic of China and the European Union – have been exposed as highly dysfunctional."[100] Being big, as the proponents of this idea argue, entails diseconomies of scale: countries or empires have grown so large as to reach a threshold beyond which they cannot effectively govern themselves. This in turn is the reason why small economies like Singapore, Iceland, South Korea and Israel seem to have done better than the US in containing the pandemic and dealing with it.

-

The small countries in some cases did better with the pandemic, but others (Israel) did not. That said, I think the idea of diseconomies of scale is on point. Too big too fail is a blatant example of this.

page 97 (98):

-

The very essence of their fragility – weak state capacity and the associated inability to ensure the fundamental functions of basic public services and security – makes them less able to cope with the virus. The situation is even worse in failing and failed states that are almost always victims of extreme poverty and fractious violence and, as such, can barely or no longer perform basic public functions like education, security or governance.

-

Playing devil’s advocate, a state that is hit hard with covid and has their population reduced greatly may become more resilient. Less population density means less spread. If other states “manage” covid with lockdowns their economies may falter while the fragile-come-agile state now dominates.

-

Second, why is education a public function? Homeschool? Security I can maybe agree with at the nations at war level, but security in day-to-day life should also be handled at the local (read: personal) level. Interestingly, a well armed population solves both the problems of local security and potential invasion; it does nothing for industrial invasion (bombs, etc).

1.5. Environmental reset

page 102 pdf (103):

- At first glance, the pandemic and the environment might seem to be only distantly related cousins; but they are much closer and more intertwined than we think. Both have and will continue to interact in unpredictable and distinctive ways, ranging from the part played by diminished biodiversity in the behaviour of infectious diseases to the effect that COVID-19 might have on climate change

page 107 pdf (108):

-

It is too early to define the amount by which global carbon dioxide emissions will fall in 2020, but the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates in its Global Energy Review 2020 that they will fall by 8%.[109]

-

Considering the severity of the lockdowns, the 8% figure looks rather disappointing. It seems to suggest that small individual actions (consuming much less, not using our cars and not flying) are of little significance when compared to the size of emissions generated by electricity, agriculture and industry, the “big-ticket emitters” that continued to operate during the lockdowns (with the partial exception of some industries).

page 109 (pdf 110):

- the COVID-19 crisis cannot go to waste and that now is the time to enact sustainable environmental policies.

page 110 (pdf 111):

-

Low oil prices (if sustained, which is likely) could encourage both consumers and businesses to rely even more on carbon-intensive energy.

-

Klaus gets another one wrong.

-

Some leaders and decision-makers who were already at the forefront of the fight against climate change may want to take advantage of the shock inflicted by the pandemic to implement long-lasting and wider environmental changes. They will, in effect, make “good use” of the pandemic by not letting the crisis go to waste. The exhortation of different leaders ranging from HRH the Prince of Wales to Andrew Cuomo to “build it back better” goes in that direction. So does a dual declaration made by the IEA with Dan Jørgensen, Minister for Climate, Energy and Utilities of Denmark, suggesting that clean energy transitions could help kick-start economies: “Around the world, leaders are getting ready now, drawing up massive economic stimulus packages. Some of these plans will provide short-term boosts, others will shape infrastructure for decades to come. We believe that by making clean energy an integral part of their plans, governments can deliver jobs and economic growth while also ensuring that their energy systems are modernised, more resilient and less polluting."[112] Governments led by enlightened leaders will make their stimulus packages conditional upon green commitments. They will, for example, provide more generous financial conditions for companies with low-carbon business models.

page 111 (pdf 112):

-

a significant number of us saw and smelled for ourselves the benefits of reduced air pollution

-

They saw and smelled the 8% reduction of CO2? Obviously there are many other pollutants, but I am skeptical that anyone would smell a difference (unless in a place that was really smelly). I am unconvinced but willing to entertain this.

-

Our consumption patterns changed dramatically during the lockdowns by forcing us to focus on the essential and giving us no choice but to adopt “greener living”.

-

In a lockdown, wouldn’t economic survival take center stage? You’ve lost your job or you fear you may so you weight cost as the most important metric to decide what to consume.

1.6. Technological reset

page 116 (pdf 117):

-

Our mobile devices have become a permanent and integral part of our personal and professional lives, helping us on many different fronts, anticipating our needs, listening to us and locating us, even when not asked to do so…

-

Drawing on [[fourth_industrial_revolution%2Ffourth_industrial_revolution_-_Klause_Schwab-notes]]

-

one of the greatest societal and individual challenges posed by tech: privacy.

page 117 (pdf 118):

-

positioned to become an enabler of mass surveillance.

-

contact tracing

page 118 (pdf 119):

-

During the lockdowns, a quasi-global relaxation of regulations that had previously hampered progress in domains where the technology had been available for years suddenly happened because there was no better or other choice available. What was until recently unthinkable suddenly became possible, and we can be certain that neither those patients who experienced how easy and convenient telemedicine was nor the regulators who made it possible will want to see it go into reverse. New regulations will stay in place. In the same vein, a similar story is unfolding in the US with the Federal Aviation Authority, but also in other countries, related to fast-tracking regulation pertaining to drone delivery. The current imperative to propel, no matter what, the “contactless economy” and the subsequent willingness of regulators to speed it up means that there are no holds barred.

-

More “opportunities” to roll out the technology that, literally in the last paragraph, Klaus says isn’t as good as the “real thing”. (WhatsApp family group vs seeing your family, online learning vs in person, cycling class online vs in person)

page 119 (pdf 120):

- the enduring concerns about technological unemployment will recede as societies emphasize the need to restructure the workplace in a way that minimizes close human contact.

page 121 (pdf 122):

- Successful contact tracing proved to be a key component of a successful strategy against COVID-19.

page 122 (pdf 123):

-

allowing public-health officials to identify infected people very rapidly

-

it not only allows backtracking all the contacts with whom the user of a mobile phone has been in touch, but also tracking the user’s real-time movements, which in turn affords the possibility to better enforce a lockdown and to warn other mobile users in the proximity of the carrier that they have been exposed to someone infected.

page 123 (pdf 124)

-

TraceTogether app run by Singapore’s Ministry of Health. It seems to offer the “ideal” balance between efficiency and privacy concerns by keeping user data on the phone rather than on a server, and by assigning the login anonymously.

-

There still needs to be some centralized data. If someone is infected, how would all the users that came in contact be identified?

-

Bluetooth identifies the user’s physical contacts with another user of the application accurately to within about two metres and, if a risk of COVID-19 transmission is incurred, the app will warn the contact, at which point the transmission of stored data to the ministry of health becomes mandatory (but the contact’s anonymity is maintained).

-

So how does it actually work then? How does it know (before accessing the server) that there is a “risk”? Even if both users' have a log of where they have been, how would you know if you were in contact with an infected person? The infection would be seen at a later point and somehow would need to be pushed to everyone they came in contact with to let future contacts know there was a “risk”. This seems like bullshit.

page 124 (pdf 125):

-

Margrethe Vestager, the EU Commissioner for Competition: I think it is essential that we show that we really mean it when we say that you should be able to trust technology when you use it, that this is not a start of a new era of surveillance.

-

Trust is a four letter word to me.

page 126 (pdf 127):

-

As the coronavirus crisis recedes and people start returning to the workplace, the corporate move will be towards greater surveillance; for better or for worse, companies will be watching and sometimes recording what their workforce does. The trend could take many different forms, from measuring body temperatures with thermal cameras to monitoring via an app how employees comply with social distancing.

-

Said so matter-of-factly.

-

the surveillance tools are likely to remain in place after the crisis and even when a vaccine is finally found, simply because employers don’t have any incentive to remove a surveillance system once it’s been installed

-

This is what happened after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. All around the world, new security measures like employing widespread cameras, requiring electronic ID cards and logging employees or visitors in and out became the norm. At that time, these measures were deemed extreme, but today they are used everywhere and considered “normal”.

page 127 (pdf 128):

- Most people, fearful of the danger posed by COVID-19, will ask: Isn’t it foolish not to leverage the power of technology to come to our rescue when we are victims of an outbreak and facing a life-or-death kind of situation? They will then be willing to give up a lot of privacy and will agree that in such circumstances public power can rightfully override individual rights.

Chapter 2. MICRO RESET (INDUSTRY AND BUSINESS)

page 131 (pdf 132):

- micro level, that of industries and companies

2.1. Micro trends

page 133 (pdf 134):

-

“online” should be the largest beneficiary of the pandemic

-

It is not by accident that firms like Alibaba, Amazon, Netflix or Zoom emerged as “winners” from the lockdowns.

page 136 (pdf 137):

-

“just-in-case” will eventually replace “just-in-time”

-

supply chains.

page 139 (pdf 140):

-

Most likely, in our post-pandemic world increases in the minimum wage will become a central issue that will be addressed via the greater regulation of minimum standards and a more thorough enforcement of the rules that already exist. Most probably, companies will have to pay higher taxes and various forms of government funding (like services for social care).

-

Both of these things will push prices up, negating any wage increases.

2.2. Industry reset

page 144 (pdf 145):

- services represent about 80% of total jobs in the US

page 145 (pdf 146):

-

Small businesses are the main engine of employment growth and account in most advanced economies for half of all private-sector jobs. If significant numbers of them go to the wall, if there are fewer shops, restaurants and bars in a particular neighbourhood, the whole community will be impacted as unemployment rises and demand dries up, setting in motion a vicious and downward spiral and affecting ever greater numbers of small businesses in a particular community. The ripples will eventually spread beyond the confines of the local community,

-

This is basically what I WANT via a general boycott. Painful? Yes. Although I see no way out of the consumer-driven money-over-everything world we live in.

-

big businesses will get bigger while the smallest shrink or disappear.

-

The bigger the business the more likely they can weather the storm.

page 148 (pdf 149):