Home · Book Reports · 2018 · The Sleep Solution - Why Your Sleep Is Broken and How to Fix It

- Author :: W. Chris Winter

- Publication Year :: 2017

- Read Date :: 2018-12-04

- Source :: The_Sleep_Solution_- Why_Your_Sleep_is_Broken_and_How_to_Fix_It.epub

designates my notes. / designates important.

Thoughts

Chapter one introduces the ideas to be presented and gives a few salient examples to whet your appetite. First and foremost is what I would consider both the most important point in this or any book about health:

“…the three main pillars of good health that we can exert some control over are nutrition, exercise, and sleep…”

Two examples of some of the startling claims in support of sleep:

Amyloid beta (Aβ), is a protein that accumulates in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients. It is removed by what is known as the glymphatic system. This system is 60 percent more productive when we sleep than when we are awake!

The World Health Organization classifies shift work (sleep wrecking) as a class 2A carcinogen!

Chapter two lets you know that, even though you might not feel like it: you sleep. Period. You might not sleep well, or enough, or too much, but in the end you sleep. Or else you die. This is a little teaser for when you get to the insomniac chapter.

How much you sleep or how much you need to sleep is different for everyone.

From newborn to old-age, sleep requirements decline as we age. From 16-ish hours to 7-ish.

Newborns (to 3 months) = 14-17 hours

Infants (4-11 months) = 12-15 hours

Toddlers (1-2 years) = 11-14 hours

Preschoolers (3-5) = 10-13 hours

Children (6-13) = 9-11 hours

Teens (14-17) = 8-10 hours

Adults (18-64) = 7-9 hours

Adults (65+) = 7-8 hours

Chapter three compares fatigue to sleepiness; they are not the same thing. Next the book looks at the homeostatic and circadian systems regulate sleep. These are interesting and while their effects are probably common sense to most, the underlying physiology is likely not.

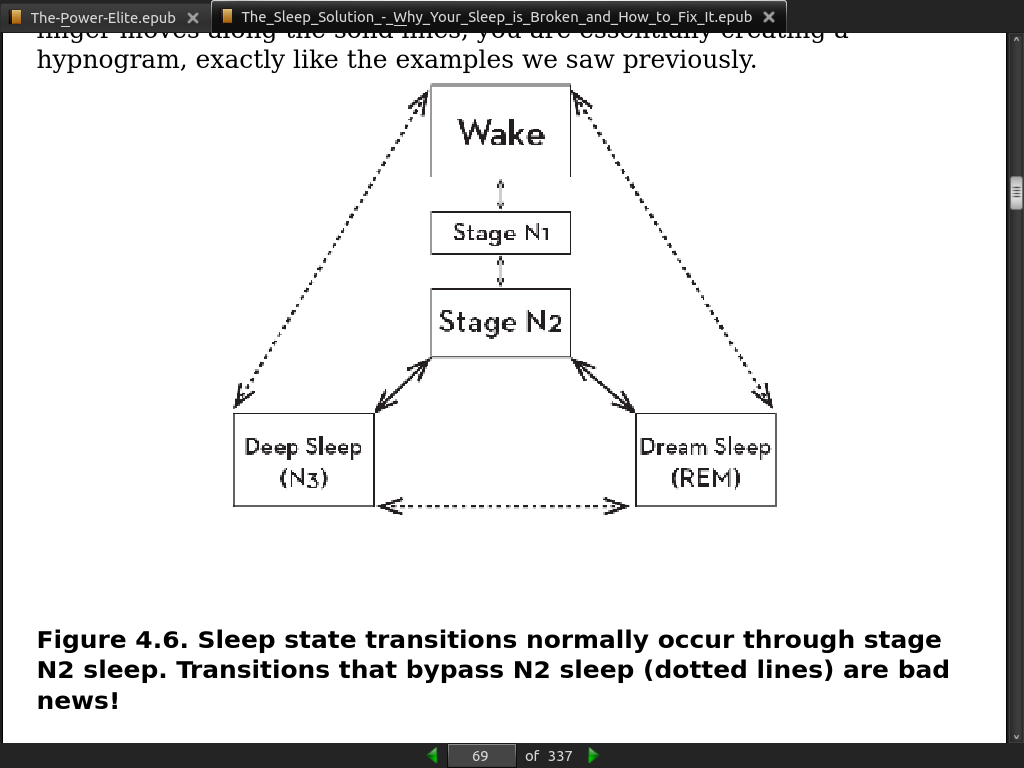

Chapter four continues to explain the scientific side of sleep. The phases of sleep, called cycles, generally run about 90 minutes give or take. Don’t forget that everyone is different though. Don’t try to follow some crazy sleep schedule you read about in books or online; listen to your body.

Years ago when I researched sleep for the first time there used to be four phases to sleep, but this has been reduced to 3 (plus REM).

Chapter five covers a host of drugs and chemical naturally occurring that relate to sleep. Some drugs that cause sleepiness and vigilance. Vigilance decreases throughout the day, sleepiness increases, it is constant march toward sleep as soon as you wake up.

Chapter six is where a lot of people probably start reading: insomnia. More accurately: paradoxical insomnia. This is when you are sleeping but not feeling like you are sleeping. You sleep will often feels shorter than it really is, but by God you are sleeping.

The author goes out of his way to ease people into this chapter. For those who think they ’never sleep’, it can be crushing to find out you actually DO sleep, but poorly. He points out that insomnia, most often self-diagnosed, can: 1. become a defining feature of you, and 2. will usually be ’treated’ hastily by overworked general practitioners with a quick fix: sleeping pills.

Chapter seven looks into circadian rhythms and how they are affected by routines and environmental conditions. There are cues throughout the day that set and reset the clock, fine tuning it to the individual’s behavior. On average the human circadian rhythm is set to a 24 hour and eleven minute clock.

Our bodies generally anticipate, or rather prefer to anticipate, rather than react to changes. For example if you follow a regular schedule -wake up at the same time, exercise, eat breakfast, etc- at the same time every day, your clock will set itself to this schedule. If then you try to change the schedule, your body will at first protest. You will wake up at the same time, even though you’ve set your alarm for an hour later. You will feel restless when you skip your exercise. You will feel hungry even though you plan on eating later. You body anticipates what is coming, it does not react. Of course you can, within a few weeks, retrain your body to your new schedule. This is one of the reasons shift work is so taxing; your body never settles into a set pattern.

Chapter eight lays out some principles for good sleep hygiene. First and foremost: remove all light! Light wakes you up by inhibiting melatonin production. If you can see your hand in front of your face, it is too light.

Next, if you are having trouble sleeping, one of the main culprits might be who you sleep with. This can include children and pets in addition to spouses. The author, suggests that (a) you should not sleep with children as it will train them to sleep only with mom and dad instead of on their own, and (b) if you are troubled or troubling your sleep partner you might experiment sleeping in separate rooms. This, he admits, might seem almost taboo, but I completely agree with the assessment. Sleeping in separate rooms can, in addition to alleviating sleep problems, also afford each person a kind of sanctuary; a place all their own. In regards to sex, this arrangement has been shown to increase intimacy by creating a sort of fantasy where you can steal away to the private room of your lover before returning to your bed (or sleeping with them occasionally) for a good night’s sleep.

Before sleeping one should not, and this seems quite the common sense, not smoke nicotine, drink alcohol, or eat within a few hours. There are some food, like tart cherries for example, that promote sleep, but for the most part food should be avoided.

Chapter nine is probably the most popular chapter. It deals with insomnia. Simple insomnia actually, as opposed to the hard insomnia of chapter ten. Simple insomnia is simply getting a little less sleep here and there and it is often no big deal. The difficulty comes with the associated anxiety and stress (often about not sleeping) that can lead to not sleeping. A potentially vicious cycle. Sometimes this can be treated with basic cognitive behavioral therapy and adjustments to your sleep routine. The old trick of sleeping with your head and the foot of your bed actually has some credence, but is not probably going to help all that much. On the other hand, changing up your sleep environment, getting new comfy pillows and blankets, maybe even a new mattress, painting the walls a cools gray or redecorating the room can all help trick your body out of the stress it has likely come to associate with your old sleeping environment.

This is no silver bullet and, as always, everyone is different. Some people who sleep perfectly in the current bedroom might experience simple insomnia when changes occur; as in sleeping in a hotel room.

Chapter ten looks at hard or primary insomnia and, similar to simple insomnia is usually exacerbated by your reaction to not sleeping more than actually not sleeping. Your fear of not sleeping and the effects you’ll feel the next day are quite possibly working to keep you awake. To reiterate, fear is keeping you from sleep.

If this continues, sometimes people go decades with hard insomnia, if may become part of your identity. If you talk about your bad sleep all the time, you may unconsciously want to sleep bad since it is part of how you have come to define yourself. The author puts forth a simple exercise: a list of questions you should ask a friend. At first they are simple, essentially pointless questions, to relax your friend. Then there is the one key question: “how is my sleep?” If you talk about your sleep a lot they will be able to answer, but normally people don’t talk about their sleep. If your friend knows about your sleep, you might be talking and identifying with it.

In chapter eleven the author suggests what I think is the most important aspect of the modern perception of pills: the media promotes them as a quick fix to everything. He uses several examples of television programs that promote this idea that, while I am not familiar with, seem the rule rather than the exception.

This isn’t to say that (sleeping) pills don’t have their uses. They are perfectly acceptable temporary stop-gaps. If you are traveling and want to avoid jet lag or the difficulty you might experience in a hotel or if you are dealing with stress that is affecting your sleep as in a divorce or death, they are perfectly acceptable. They are not intended for nightly use.

Sadly, another important point the author doesn’t belabor, is that general practitioners are under more pressure to increase throughput from insurance companies. They don’t have the time (if they want the income) to spend with every patient. This leads the ’easier’ ailments, like difficulty sleeping, to be plastered over with little consideration with a quick script.

While not overt, this chapter calls into question some societal practices that are likely causing more damage than they are stopping.

Chapter twelve offers, in my opinion, some of the more useful strategies for correcting sleep problems. Number one is sleep restriction. It might seem odd to restrict the sleep of someone having trouble sleeping, but it actually ends up making perfect sense.

First, set a wake up time, say 0600. Next, set a sleep time, say 0100. This will mean you are only going to get, at most, 5 hours of sleep. You probably won’t even get that; you are having trouble sleeping after all. After a few days you’ll likely be struggling to stay up until 0100; stick with it. Pretty soon your body will understand that it only has those 5 precious hours to sleep if it wants to sleep and you’ll likely start falling right asleep.

Now, you’ll still probably be tired. Only 5 hours of sleep is not going to cut it. Finally start backing off your bed time in 15 minute increments until you start waking up feeling good. Voilà, a perfectly adjusted sleep habit.

The key to maintaining your newfound schedule is to have a single wake up time. Less important is the go-to-bed time. You should not sleep in on weekends; wake up at the same time every day. Sorry shift-workers, you’re out of luck.

Chapter thirteen explores naps and their proper usage. Naps should generally range between 15-25 minutes, otherwise you run the risk of descending into deep sleep (N3) and will be a grouch when you wake up from that stage. As with all sleep, light, or rather dark, is key to a solid nap. When you first wake from your nap, light will help you regain your alertness quickly, the same way light in the morning, usually naturally provided by the sun, helps to get you out of bed.

If you are one prone to taking naps, it is best that you try to follow, as with all sleep, a schedule. You should try to take the nap at the same time everyday. You don’t actually need to take a nap ever day, but when you do take a nap a consistent time will be valuable.

It is, apparently, said that naps earlier in the day help with last night’s sleep while naps later in the day rob tonight’s sleep.

That said, you should only nap if you slept OK the night before. Don’t get in the habit of napping when you slept poorly, it will be harder to sleep the next night and might disrupt your schedule, often causing more harm than good. Don’t try to use naps to ‘catch up’ on you sleep debt. You can, within the next few days of missing out on some sleep, make it up by going to bed a little earlier.

Sleep apnea and its ill effects on you health are discussed in chapter fourteen. Sleep apnea, compared to rust, takes a toll over time. There are a host of problems that worsen as someone suffering sleep apnea continues to live with it. The least of which are not substantially interrupted sleep with the constant breathing interruptions.

It is not the same thing as snoring, but snoring usually occurs with sleep apnea.

Chapter fifteen covers a number of sleep disorders which need not be listed here.

Chapter sixteen examines sleep studies. It gives multiple images of various reading one might see during a sleep study and often asks the reader to interpret what is being show given the knowledge they’ve gained in the rest of the book.

Most of the sleep studies are done in a hospital or hotel, but more and more are being billed as in home sleep studies. The thing is, these home sleep studies don’t record the data required to tell you much of anything about your sleep. They focus on breathing and heart rate, but without being able to record mental activity, these are all but useless for diagnosing actual sleeping.

The author concludes that you should be wary of these in-home sleep studies. As with the insurance companies mucking around with doctor/patient relationships, the same thing seems to be occurring with sleep studies. The in-home studies are so much cheaper that they are pushed as a first test and then, when they are inconclusive, further testing is required but often not provided.

Table of Contents

- 01: WHAT IS SLEEP GOOD FOR? ABSOLUTELY EVERYTHING!

- 02: PRIMARY DRIVES: Why We Love Bacon, Coffee, and a Weekend Nap

- 03: SLEEPY VERSUS FATIGUED: Too Tired for Your BodyPump Class or Falling Asleep on the Mat?

- 04: SLEEP STAGES: How Deep Can You Go?

- 05: VIGILANCE AND AROUSAL: (Sorry but Not That Arousal)

- 06: SLEEP STATE MISPERCEPTION: How Did This Drool Get on My Shirt?

- 07: CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS: The Clock That Needs No Winding

- 08: SLEEP HYGIENE: Clean Bed Equals Sleepyhead

- 09: INSOMNIA: I Haven’t Slept in Years, Yet I’m Strangely Still Alive

- 10: HARD INSOMNIA: Please Don’t Hate Me When You Read This

- 11: SLEEPING AIDS: The Promise of Perfect Sleep in a Little Plastic Bottle

- 12: SLEEP SCHEDULES: I’d Love to Stay and Chat, but I’m Late for Bed

- 13: NAPPING: Best Friend or Worst Enemy?

- 14: SNORING AND APNEA: Not Just a Hideous Sound

- 15: OTHER SLEEP CONDITIONS SO STRANGE, THEY MUST BE SERIOUS

- 16: TIME FOR A SLEEP STUDY

- Pages numbers from the pdf.

· WHAT IS SLEEP GOOD FOR? ABSOLUTELY EVERYTHING!

page 19:

- the three main pillars of good health that we can exert some control over are nutrition, exercise, and sleep.

page 21:

-

researchers Antoine Louveau and Aleksanteri Aspelund that the brain does in fact have a system for removing waste: the glymphatic system. Although scientists today generally agree on its existence, it was another aspect of the glymphatic system that really grabbed headlines. Scientists discovered that the main waste product the glymphatic system is removing is amyloid beta (Aβ), the protein that accumulates in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. While that fact itself is fascinating, there’s more:

-

The glymphatic system is 60 percent more productive when we sleep than when we are awake!

page 22:

- One last thing about the glymphatic system: it seems to work better when you sleep on your side.

page 29:

- In 2007, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a monograph titled “Carcinogenicity of Shift-Work, Painting, and Fire-Fighting.” Let that sink in. Not only is the WHO grouping shift work with inhaling paint fumes and smoke from burning houses in terms of causing cancer, but it is listing shift work first on the marquee! In this early investigation, researchers found a relationship between shift work and breast cancer as well as a general decline in immune system functioning. Subsequent research surrounding shift work in particular has led the International Agency for Research on Cancer, an agency of the World Health Organization, to classify shift work as a probable (group 2A) carcinogen.

· 02: PRIMARY DRIVES: Why We Love Bacon, Coffee, and a Weekend Nap

page 39:

-

For the newborn group (up to three months), it was recommended they get fourteen to seventeen hours of sleep each day. Previously a range of twelve to eighteen hours was allowable. No more. Now if your baby is getting twelve to thirteen hours of sleep, you are failing as a parent. 24 Infants aged four to eleven months have two hours taken away. Their range of twelve to fifteen hours represents an expansion based on the previous recommendation of fourteen to fifteen hours.

-

Toddlers (one to two years) have an hour taken away to arrive at eleven to fourteen hours. Preschoolers (three to five years) have another hour lopped off, for a recommended ten to thirteen hours. Both toddlers and preschoolers gained an hour compared to previous recommendations.

-

Pretty much the same goes for school-age children (six to thirteen years). They should be sleeping nine to eleven hours before waking up, going to school, and not being left behind. Teens (fourteen to seventeen years) lose an hour compared to their annoying little siblings and get to spend only eight to ten hours in bed.

-

Finally, younger adults and adults (eighteen to twenty-five and twenty-six to sixty-four years) drop an hour to seven to nine hours.

-

In a cruel, ironic twist of fate, older adults who have finally arrived at retirement and a childless home need only seven to eight hours of sleep, leading them to continually ask, “What do I do with the other sixteen hours of my day? There’s nothing good on TV anymore.”

· 03: SLEEPY VERSUS FATIGUED: Too Tired for Your BodyPump Class or Falling Asleep on the Mat?

page 56:

- Melatonin is produced in conditions of darkness. When your eyes (retina)see darkness, a collection of cells called the intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) 36 is responsible for receiving the signal and sending it to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the brain’s timekeeper. It’s the suprachiasmatic nucleus that prompts the pineal gland, a little pea-size gland in the brain, to release melatonin. Because melatonin makes us sleepy, we tend to feel sleepier at night and more awake during the day. It is interesting that raccoons have the opposite response to melatonin, which is helpful because their survival depends on sneaking around at night to find food in trash cans. Located within the SCN, the circadian pacemakers of the brain work to counteract the buildup of homeostatic sleep pressure occurring during the day. This system modifies the homeostatic pressure curve to make it look like that shown in figure 3.4 on page 50. Now, the relentless homeostatic drive to sleep is kept in check later in the day so you can get some things done. However, as bedtime approaches, the SCN can no longer keep a lid on things, and the big release of sleep inducing melatonin occurs. Sleep soon follows.

· 04: SLEEP STAGES: How Deep Can You Go?

page 66:

- during REM sleep, you stop regulating your body temperature. Think about that. During dreaming, your brain completely suspends the fundamental and complicated function of temperature regulation. 40

page 67:

- Why is deep sleep restorative? Mainly because the time you spend in deep sleep happens to also be the time of greatest growth hormone (GH) production.

page 68:

page 69:

· 05: VIGILANCE AND AROUSAL: (Sorry but Not That Arousal)

· 06: SLEEP STATE MISPERCEPTION: How Did This Drool Get on My Shirt?

· 07: CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS: The Clock That Needs No Winding

page 96:

- Circadian (Latin for circa, “about” + a dian, “day”)

page 98:

-

human circadian rhythms are twenty four hours and eleven minutes

-

we need time cues like the sun to help set our internal clock every day. These cues are referred to as zeitgebers, and the sun is probably the strongest of the bunch.

-

Other zeitgebers are mealtimes, exercise, social interactions, temperature, and sleep. These clues to our external time happen frequently and give our bodies cues as to how to adjust its internal time. The more zeitgebers an individual is exposed to, particularly cues that are presented at uniform times every day, the more synchronized an individual’s circadian rhythm.

· 08: SLEEP HYGIENE: Clean Bed Equals Sleepyhead

page 111:

- In a 2014 study by Charles Czeisler, individuals who used e-readers before sleep at night took an average of ten minutes more to fall asleep and had less REM sleep than individuals who read a printed book with indirect light.

page 115:

- For many (I’m speaking from clinical experience here and not personally, of course), spouses can be a real problem for their partner’s sleep.

page 116:

- Advice for couples to potentially sleep in separate rooms.

page 121:

-

the National Sleep Foundation feels it best not to eat any of it within two to three hours of bedtime. While there is no definitive research as to precisely how long to wait between food and sleep, this is probably a good number and should help you avoid the sleep disturbances some people feel from indigestion or gastroesophageal reflux if they go to bed too soon after eating. Foods heavy in protein can have the unwanted effect of keeping you up at night.

-

Look for dried fruit, cereal, or bananas. High-glycemic-index foods produce sleepiness, so if food must be consumed at night, these are good choices. Other foods that are good choices for sleep contain high amounts of melatonin. These foods include walnuts and tart cherries (dried or juice). Foods high in tryptophan are sleep promoting because tryptophan is the building block of melatonin. Game meat like elk and chickpeas are high in tryptophan content. Finally, foods high in magnesium (almonds) and calcium (milk, kale) can help promote relaxation and sleep. When it comes to sleep promotion, hot chamomile tea or passionflower tea can also be helpful. 56 Sweeten the tea with honey, itself sleep promoting, for an added kick. Avoid proteins that can often promote the synthesis of dopamine, a wake-promoting neurotransmitter.

· 09: INSOMNIA: I Haven’t Slept in Years, Yet I’m Strangely Still Alive

· 10: HARD INSOMNIA: Please Don’t Hate Me When You Read This

· 11: SLEEPING AIDS: The Promise of Perfect Sleep in a Little Plastic Bottle

page 160:

-

There is a tremendous media machine that is churning out fear and misinformation about sleep. It comes in the form of funny television characters, like Karen Walker from Will & Grace, who embody what is portrayed as a modern approach to sleep. Reading between the lines, the viewer is told, “Nobody struggles with insomnia anymore. We just take a pill,” leaving the viewer to feel a little dumb for actually trying to just get into bed and fall asleep without help.

-

In countless episodes, Karen would announce to anyone who was around how essential her alcohol or medication consumption was to her sleep. Among her more memorable lines: “Normally my motto is ‘Drugs not hugs’”; “Plus, I’m high most of the time, so there’s that”; and “I may be a pill-popping, jet-fuel-sniffing, gin-soaked narcissist . . .” This character is clearly over-the-top. In one episode, she uses her Valium pills and other medications as color swatches to help an expecting couple plan out how to paint their new home.

· 12: SLEEP SCHEDULES: I’d Love to Stay and Chat, but I’m Late for Bed

page 184:

- The single most important thing to achieving successful sleep is to have a consistent wake time

· 13: NAPPING: Best Friend or Worst Enemy?

page 189:

- An early nap adds to the previous night of sleep but a late nap subtracts from the upcoming night of sleep. I have never seen a study proving this, but it makes sense to me, and because it’s my sleep book, we’re going with it.

· 14: SNORING AND APNEA: Not Just a Hideous Sound

· 15: OTHER SLEEP CONDITIONS SO STRANGE, THEY MUST BE SERIOUS

page 213:

- Currently, there are approximately eighty-five recognized sleep disorders.