Home · Book Reports · 2018 · Homo Deus

- Author :: Yuval Noah Harari

- Publication Year :: 2016

- Read Date :: 2018-08-08

- Source :: Homo_Deus__A_Brief_History_of_Tomorrow_-_Yuval_Noah_Harari.epub

designates my notes. / designates important.

Thoughts

This was an extremely interesting book to read. Not for the ideas within, but as a look into the thought process of a (trans) humanist. The ideas, and their arguments, range from obvious to absurd while some of the values the author takes for granted are enlightening.

Overall, while interesting, the book is also quite infuriating. There are many logical gaps, some of which are blatant. For example, “God is dead” is repeated a dozen times, but does this really correspond with reality? I think something like half of the people in the USA believe the earth to be only a few thousand years old. That doesn’t sound dead to me. Then it talks about these future god-like abilities man will develop via technology. It is made to sound, again explicitly, as heaven on earth. How is this singularity any different from the second coming of Christ?

Chapter By Chapter

The book begins by talking about how humans, once ravaged by war, famine, and plague, has been freed of living on a knife edge by modern advances in science. This idea, that humans, until now, had to spend all of their time barely scraping by does not sit with me. Though I don’t have any hard data to back it up, it seems to me that a hunter-gather or a subsistence agriculturist would have had ample ‘free time’. After the hunt or harvest the stores are full for the coming winter, and duties can relax. Only during the planting and harvesting would the agriculturist be taxed heavily.

Culture and art, let alone all of the various religions, also seem to support that man has had enough time off from scraping by to invent numerous elaborate systems.

Either way, we are in for a massive change. So claims the author. Immortality, cyborgs, and inequality are all set to take off. While Yuval hedges his bets, saying these are not predictions, but more a guide for current choices, they sound an awful like predictions and/or predictive programming.

He sees history as a random chain of events, later pointing out that there could never be any conspiracy to shape history because it is simply too complex. Quigley, Sutton, and Gato, among others, would probably beg to differ.

An interesting example he gives is in regard to lawns. He puts for that they are derived from aristocracy; you had to have a lot of wealth to let land be unproductive. I was under the impression that this can go back to the crusades where the knights saw the lawns of the Taj Mahal, and brought the idea back.

Funny enough, this dominant feature of the world can be seen from the Midwest USA all the way to the Middle East, where lawns are kept green with extensive irrigation. Again a sign of wealth to have a verdant lawn amidst a desert backdrop. My first thought was, ISIS is spreading its horrible values again, trying to force its ways onto the world… oh, wait, that is western society!

The historical lacuna presented by the question: why do we have lawns, is supposed to show you that you are free to change your patterns, plant a forest instead of a lawn. You don’t have to be slave to the past, especially since you probably don’t even know about the past. This is something I can’t disagree with.

Next the book takes a quick look at Watson and Harlow, and their tactics for raising children after experimenting on monkeys. The author dismisses these tactics as dead ideas. I’m not so sure; with the appropriate lens the concepts still seem to be valid today. Not that I’m defending these monsters, but after just harping about not understanding our history, he tries to discard some unpleasant, but enlightening history. There is the briefest mention of evolutionary psychology.

We now move from the sciences to the religions. From animist to humanist. In the beginning, Christians, Jews, Muslims, or whoever else, considered man as the center of the universe. The animals and plants, which were all parts of older religions, were transformed into mere props that God and Man acted against.

This, the author concludes, happened around the rise of agriculture, when man started asking god for good crops, not the plants and animals directly. This rings true with other accounts I’ve read. The Sacred Mushroom being on example.

Moving to the modern, we see animal farming abuses allowed by science. Vaccines, air-conditioning, antibiotics, and the like, have made modern animal farming possible. Packing too many animals in too tight a space would have, before antibiotics, led to an outbreak of a disease at best and maybe even a plague.

This is where man started becoming a god. He even created a new garden, Newton’s garden, complete with a new apple of knowledge.

Since humans see themselves as the center of the universe, the apex of evolution, and we treat lesser animals so cruelly, what happens when a super artificial intelligence is created that views humans the same way humans view cows? This introduces on of the main themes of the book: super AI is on the way.

Chapter three asks why everyone gets up in arms over Darwin and the theory of evolution, but not so much as a peep is made about quantum mechanics, relativity, etc. On this, I call bullshit. Evolution is merely more of a hot button, there are plenty of people that criticize quantum mumbo-jumbo and relativity. The difference is, they aren’t all that outspoken like some orthodox religious upstart.

Somehow Yuval twists the idea of an evolving eye, which has historically been seen as the counter-example that evolution doesn’t provide for. There is no mention of, as with Koestler’s work, how amphibian eggs evolve piece by piece into reptile eggs. Of course the change must be all or nothing; any since piece, a hard shell, would lead to death if not for the tooth to escape, the water and nutrients inside, and the digestive system to segregate waste before hatching.

Another turn takes us to the question: what is consciousness? At least here he admits that no one has even the slightest idea, but don’t worry, it is probably just biochemical and electric responses. Scientists can simulate emotion with electric charges, so, even if we don’t know how it works, we can still manipulate it. Whatever it is.

The general comparison, the mind to computers, is criticized. When the steam engine was new technology, men compared the mind to steam engines, talking about pressures and releases of emotion and feeling. Could our current analogy be wrong? I think this is a very valid complaint, but Yuval spends the rest of the book essentially backpedaling, stating again and again that organisms are algorithms.

Since we don’t know where the mind and brain are ‘split’, could we already be living in a virtual reality? This is one of the more absurd ideas, however technically possible, that is bandied about considerably in recent years. The proof? Well, mathematicians say that infinite virtual worlds are possible, where as the would only be one real world. Therefore, the possibility we are living in a virtual world is almost guaranteed. QED. Sigh.

After discussing cooperation, that man can do better than most (all) other animals, he comes to the bonobo. Bonobos are said to resolve conflict with sex, not war. Yuval makes it a point, though it doesn’t seem to matter in the realm of arguing for cooperation, that there is a lot of homosexual behavior in bonobos. This couldn’t be slipped in to promote the LGBT lifestyle strangling culture today, could it?

In the end, Yuval concludes, everything we believe is a fiction somewhere in between objective and subjective reality. Google, God, Money, and lawsuits are all common stories, fictions, that bind us just like the old religious stories that no one believes in. What? That is right, he said, and repeats many times, that God is dead, religion is dead, and no on believes in such nonsense anymore. Even after he says he understands that most of the world still believes, it doesn’t seem to phase him; God is dead and he won’t hear anything contrary.

There is a silver lining though, because everything we believe in is a collective fiction, humans can take advantage of this common ground to cooperate more effectively than any other animal. The major downside is that when the fiction starts to mold reality, humans tend to suffer. For example, war, and the very real human suffering it entails, is fought between fictitious nations. The same can be said about things like stock markets.

While it might seem like a good idea to ditch the fiction, it is, according to the author, the thing that keeps everyone cooperating. Our entire history is, supposedly, a web of these stories.

Yuval continues criticizing the fiction of typical religions by comparing them to the religion of science. To be fair, he is critical across the board: Christian, Muslim, or Jew. He submits that science and religion are not actually enemies and can, and have, coexisted for centuries. Religion, he states, wants order while science strives for power. I’m not sure where he comes up with this, but it isn’t, at least, totally insane sounding.

As an example he uses London and Paris of the 1600’s. They were ruled by religious intolerance and yet modern science has its roots here. On the other hand, Cairo and Istanbul were secular during the same period yet produced nothing like the Enlightenment of Europe.

As an aside to the argument here, it is noteworthy to point out that we, again, see a lot of superfluous pro homosexual language in addition to anti-Nazi positions. To be fair, there is also criticism of communism here and elsewhere in the book.

Chapter 6, in my opinion, is the most interesting chapter of the book. It starts with the ‘miracle’ of credit and how it alone is responsible for bringing about the modern world. He speaks of the global economy as not being a zero-sum game, but his examples do not stand up to basic arguments.

He argues that knowledge is not a limited resource, and with it we can create more resources. I agree that knowledge is unlimited and it can reduce or make more efficient use of existing resources, but it can never create new resources. There is only so much iron or oil or helium on earth. That is a zero-sum game no matter how you want to obscure it with credit and currency. No amount of knowledge can replace logs needed for a log cabin. You can build the cabin out of something else, but that just passes the buck. The something else, once depleted, can also not be replaced with knowledge.

In the simplest terms, everything on earth comes from earth. It sounds almost ridiculous, but no amount of money, that only exists in the mind, can account for finite limited resources.

That isn’t to say I am preaching the end of the world, but there is a limit. Where is it? Who knows, but it is there.

Next, in basically the same argument, he says that humans can discover new materials and sources of energy.

Indeed, when you increase your stock of knowledge, it can give you more raw materials and energy as well. If I invest $100 million searching for oil in Alaska and I find it, then I now have more oil, but my grandchildren will have less of it. In contrast, if I invest $100 million researching solar energy, and I find a new and more efficient way of harnessing it, then both I and my grandchildren will have more energy.

What are we building the panels out of? Whatever it is, it is limited by the amount on earth.

While humans might discover new materials, what is more accurate to say is humans can synthesize new materials FROM EXISTING MATERIALS. At the end of the day, we are stuck with what is on earth. Sure, you can turn oil into plastic, but you are unlikely to discover unobtanium deposits that revolutionize industry. Similarly, we might find ways of extracting energy from existing materials, but we aren’t going to find new SOURCES.

Where does all this lead? A social contract that Yuval calls a covenant. The covenant of free-market capitalism. This covenant says that problems are fixed with ‘more stuff’ and that ‘more stuff’ is better than community, families, and values, all of which can and will be destroyed in the pursuit of ‘more stuff’.

If economic growth demands that we loosen family bonds, encourage people to live away from their parents, and import carers from the other side of the world – so be it.

Whereas previously social and political systems endured for centuries, today every generation destroys the old world and builds a new one in its place. As the Communist Manifesto brilliantly put it, the modern world positively requires uncertainty and disturbance. All fixed relations and ancient prejudices are swept away, and new structures become antiquated before they can ossify.

This whole chapter seems to be nothing more than wishful thinking wrapped up in a knowledge based economy, forgetting the material foundation of… everything, and using this fiction (they allow us to cooperate, right?) to justify the destruction of values, families, and anything else we might have once called sacred.

Chapter 7 continues the same reasoning. He is constantly harping that God is dead. He repeats it every few chapters, yet tons (the majority) or people still believe in God, whatever form it may take. Even humanism is nothing more than a retelling of ancient stories. The singularity is nothing more than the second coming of Christ. Eternal bliss in heaven versus immortality on a heavenly earth, what’s the real difference? I like to say there is nothing different between angels or aliens, simply two matrices people view the world through.

Nietzsche pronounced God dead. He seems to be making a comeback, says the author, but that is a mirage.

The author calls on Rousseau as support for the whatever I feel is right/wrong is right/wrong. Adultery, for example, is based on feelings. And it can be OK. If the feelings that drove you into one person’s arms now drive you into another’s, who are you to say it is wrong? This is modern ethics in a nutshell: if it feels good, do it!

Later he mentions adultery in the context of living exceptionally longer lives. What if, after having a child at 30 years old and raising it until 50, a woman wants to start a new life, with a new partner? He says that the child-rearing time period would be a lifetime away, and, since humans might be living to 150 or more years old, the woman still has plenty of life left in here. Again, I see this as a thinly veiled justification to destroy families.

In the same vein, gay is OK too. It is private after all. My first thoughts run to the pride parades and rainbows all over everything from camp grounds to police cars signaling the LGBT friendly attitude of society, not to mention the LGBT invasion of media. Nope, it is totally private.

Anticipating my reaction, Yuval offers up, perfectly reasonable in my eyes, examples where those anti-LGBT crowds claim the pride parades, etc, hurt their feelings. Even thought that is exactly what the LGBT crowd would say to my KKK march. In that case, they would be seen as right, and my KKK march would be shut down. Turn the tables and the whole thing is an exercise in intolerance. My brain hurts thinking about the mental gymnastics modern ’liberals’ engage in.

Chapter 7 continues that, since God is dead and since we know best for ourselves, it must follow that the voters know best in regard to the whole. There is, of course, not one mention of the word oligarchy in the entire book. This goes hand-in-hand with the (absurd) proposition that history is nothing more than a chain of random events. There is clearly a hand guiding, with varying success, history.

The same argument is put forth that, in the free market, the customers are always right. This is so because they have been educated. That’s right, school is there to teach you how to avoid the spin and think for yourself. What planet is this guy from? School teaches you how to be obedient and a ‘productive’ worker bee.

All of this God is dead and school is great leads into…. communism! At least Yuval doesn’t try to pull any punches here, he tells it like it is (to him).

Global peace will be achieved not by celebrating the distinctiveness of each nation, but by unifying all the workers of the world; and social harmony won’t be achieved by each person narcissistically exploring their own inner depths, but rather by each person prioritising the needs and experiences of others over their own desires.

He then goes on to explain that liberal democracy won because it threatened the world with MAD, mutually assured destruction, and not on some ideological note. One must conclude that nukes gave us the Beatles and Woodstock, sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll. This, I think, is quite accurate even though it sounds somewhat absurd. Wars, hot or cold, are used to usher in new eras. World War 2 and the Cold War tilled the ground. The Vietnam war harvested the fruit.

Marx and Lenin are referred to as visionaries, not because of their beliefs and views, but because they focused on modern economics. OK, so far it sounds reasonable. Then he tells us that communism was brought to the masses through electricity and the railroad. While I don’t doubt these inventions were useful in swaying a population, like any good carrot must do, but it seems to me that the whole idea was lower class versus upper class. Whatever your position on communism, this must be admitted still to this day. While we don’t technically have feudal lords, functionally there is little difference in the modern multi-billionaire.

This section is summed up interestingly:

If Marx came back to life today, he would probably urge his few remaining disciples to devote less time to reading Das Kapital and more time to studying the Internet and the human genome.

I’m not expert on Marx, but I’d bet he’d have quite a lot to say about the banking system.

After the communism we roll right into the next topic, the coming singularity. We are at the gates of the next revolution, so says the author, and the train is about to leave the station. Just like what happened to the less developed nations after the industrial revolution the new revolution will change the world, you don’t want to be left behind, do you? You want immortality and designer babies. You don’t want to live like those people in Sudan do you? How is this pitch for immortality different than heaven? You don’t want to miss the train to heaven and boil for all eternity, do you?

The singularity will be a revolution in evolution. It will create a class of super humans, of a certain, and I quote, tribe! You can’t make this stuff up.

Next up: what happens when the AI can outsmart you? When it can calculate your choices better than you can yourself. When it knows you better than you know yourself.

In chapter 8, Yuval, presumably since God is dead, takes a stab at nixing free-will. His first example is that scientists have implanted chips in rats’ brains that allow them to be remote controlled. This is put forth as cutting edge, where the signal makes the rat want to turn left or climb the ladder. No mention of Jose del Gato is to be found. If you didn’t know, Mr. del Gato accomplished this in rats and bulls in the late 1950s and 60s.

But wait, order today and there is a special bonus: we can already use this on humans! Since you don’t want to slice up your brain we’ve got the next best thing: transcranial direct current stimulators! That’s right, we can already “improve” you today without the need for pesky electrodes implanted into your brain.

There is literally a story that recounts exactly this. In some military research and development lab a journalist tries her hand at a combat simulator. She does… poorly. Next she puts on the magic helmet, which focuses her. After the test she asks her score, since she was so focused on the task. The attendant, somewhat amused, responds that her score was perfect. For days the journalist wished she could get her hands on the magic helmet. She said it made her mind clear for the first time in her life.

All of these brain manipulating devices are there to support that we don’t have free-will and are nothing more than biochemical/electrical responses. Push the right buttons and get whatever results you want. Yuval talks about the two conflicting people in all of us: the experiencer and the narrator. Like any good sophist, the argument is plausible. The narrator, the voice in your head that you plan with, tells us a story. It makes sense of a world that doesn’t make sense. It essentially lies to us to keep us calm. The experiencer doesn’t care about anything but what is going on right now. When you set your alarm to get up early and hit the gym, that is your narrator. When you hit the snooze button a dozen times and end up, not only skipping the gym but also late for work, that is your experiencer.

In the end we are led to believe that the experiencer is nothing more than a fleeting flash of biochemistry and the narrator, unable to really know what is actually happening, spins us a yard, however unrelated to our actual experiences, to keep us grounded in a story, any story.

Instead of using this simple example, the author decides to use some extremely out of context analogy. The State Department, the narrator, has no idea what the CIA, the experiencer, is doing droning people in Pakistan so it comes up with a reasonable story at the press conference. It will never actually know what the CIA is up to, so it simply starts believing its own story. I mention this only because of how much it stands out against the rest of the book and how it uses, of all things, the CIA droning people as its vehicle to carry the analogy.

The book reaches its climax now, with chapter 9, going so far as to say that humans will lose their economic and political usefulness, as if that is all that matters, when computers become ‘better’ in those realms. It is essentially the same story we’ve been hearing for decades: computers and robots are going to take all the jobs. This time I will agree that AI and automation will be taking a lot of jobs, but I for one don’t see this as terrible. Sure, there may be some bumpy transitions, but the main argument of this book, and others, is that humans without jobs will lose all meaning. Absurd I say. How many people love their jobs? Yet how many are defined by their jobs? Many. This will need to change, and I don’t have a good solution for it. More people are advocating for universal basic income, a concept strangely absent from this book, but I think that will create dependency. Either way, transitioning away from jobs being the defining feature of so many lives is, from what I can see, the real problem here.

Yuval does make the point that intelligence and consciousness are not the same thing. He sees that many jobs do not require consciousness: reading your fMRI, scheduling transportation, and many others. Interestingly the author goes so far as to state that in this next revolution, jobs that once were out of the reach of automation are on the chopping block. Doctors and lawyers, to name a pair, are in as much trouble as a ditch digger was with the advent of the steam shovel or the field laborer in the face of tractors. Already computers can provide superior results interpreting medical tests and litigation precedences. This superiority will only increase.

The case is then made that, with these increases, the wealthy would be able to employ the most powerful algorithms, and possibly even enhance their own bodies with implants or genetic engineering. This would create a new elite class that would then control the algorithms that in turn control the rest of the, lower caste, world.

We are already seeing an explosion in data collection of individuals. People seem to be on board with it. Fitbit and similar armbands collect biometric data and provide you with feedback on your lifestyle. There is an armband that ranks your sexual performance and another one, called Deadline, that provides you with an estimated date of death as a function of your habits and genetics.

More and more decisions will be made with this data in hand. Eventually, once the data has show to provide acceptable results, the users may authorize the AI to make decisions for them, without the bother of reviewing the data themselves. Google will read all your emails, study every biometric on you since you were born, and then ‘counsel’ you on your life choices. It will be so good, who wouldn’t do it? No privacy, but such help making decisions. From there is is only a small step to have the AI vote for you and make other important decisions:

I could have saved myself from such a fate if I only authorised Google to vote for me.

Once people have reached this point, totally detached, letting the machines make all the decisions, Yuval argues that the AI could itself, not their creators and controllers, end up owning everything. The argument goes something like this: if the AI is used to counsel an investor, and it ‘wins’ over and over, eventually the investor will let the AI make trades unsupervised. This is reasonable, we already have it today to a large degree. My question is, how do we get from here to the AI trading for itself? How do they get to be independent in the first place? If the investor owns the AI and the money being traded… it just doesn’t make sense to me.

One major pitfall to the predictions of how people will react is that the majority of studies are done on WEIRD, western educated industrialized rich and developed, people. Most of the psychology studies target WEIRD psychology students. This gives a very limited perspective on how ’normal’ people might respond to AI invading their lives. On the other hand, Alexa and similar personal assistant software seem to be selling like hotcakes.

Another objection is that the focus is on upgrading the mind instead of healing it. There is at no point in the book questions asked like: why are we all so depressed; why are suicides off the charts; why are families dissolving?

Drugs are mentioned a few times, as are alter states of consciousness, in regard to how we might want to downgrade humans so their ‘bad’ mental processes don’t cause trouble; like a smart goat culled from the herd to make them all more ruly. Never are the questions raised: what is a ‘bad’ mental process and who decided this?

The last chapter, 11, takes all of this to the next extreme. Humans aren’t even going to be needed and we should happily go extinct so that a superior data processing ‘organism’ might take our place. This is called dataism, another new age religion. The ultimate goal is not life or love, but the flow of data, the supreme stuff of the universe.

Yuval asks: what good is experiencing something if you can’t share it (online)? This makes me wonder, how many people see the world this way today? It sounds, to me at least, absurd, but how many people post everything they do online, as if to show off or validate their existence. Life isn’t worth living unless someone ’likes’ your posts. Maybe I’m old fashioned, but isn’t the experience internal? Don’t you do things you desire to do for their own sake? And once everyone is playing keep up with the (online) Jones’, won’t that end up creating a homogenized world? Certain activities will be seen as more or less acceptable. A herd mentality will solidify in the face of any outsider, pressured into conforming or being left without precious ’likes’. Truly dystopian.

Lastly we come back to the good old capitalism/communism debate. Capitalism is equated to decentralized processing while communism is equated to centralized processing. Democracy is decentralized and dictators are centralized.

Since we are all in the cloud now, we don’t have to worry about some dictator or global conspiracy where those that control the AI will use it to manipulate us, that is impossible, there is too much information. Seriously, this should be ridiculous to anyone that has studied history. There have always been people trying to ’take over the world’.

Look at the influence Hollywood has on the globe. The right movies and television programs can usher in any change Hollywood might set out to usher in. Is is a coincidence we have the rise of the internet/Facebook celebrity not long after reality TV taught us we were all everyday superstars? Did independent women and the modern feminist movement not surge after programs like Friends and Sex and the City? Is LGBT not being pushed extensively in the media right now? It doesn’t take a genius to see that, at least in this case, life will imitate art.

Yuval even concludes that modern censorship is not blocking but overloading. Knowing what to NOT look at is as important as what to look at, So, by overloading us with LGBT, all of the pro-family messages get overwhelmed.

A Study of Propaganda

In the end, this book is just another piece in a long line of propaganda. The people who are likely reading this, college indoctrinated, upper class living hollow lives, want a revolution. They want more novelty. The instant gratification world has numbed them to historical values of life, as in living not only being alive, friends, and family. These folks are so brainwashed that they think uploading their brains to the internet or robot bodies will allow them to become gods. Honestly, I feel bad for those true believers, and I despise the peddlers of such fantasies.

This is nothing more than a poorly crafted piece of sophistry that is holier than a Pope blessed block of swiss cheese. If you don’t critically think, if you drank the Kool-Aid, this probably sounds utopian. If, on the other hand, you do think critically, you’ll see the gaps in his ‘reasoning’ over and over again.

So, how did this make it on the New York Time’s best seller list? And how did the author’s last book make it there as well? I think this sums it up perfectly:

YUVAL NOAH HARARI has a PhD in history from the University of Oxford and now lectures at the Department of History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, specializing in world history. His first book, Sapiens, was translated into twenty-six languages and became a bestseller in the US, UK, France, China, Korea, and numerous other countries. In 2010 he became president of the Royal Society of Literature. He lives in London.

He is a member of the tribe, he mentioned it first. Oxford, Jew, Royal Society, global reach. A totally good guy, just like everyone else. Not a elitist piece of trash pushing the insane transhumanist (ie get rid of the humans so the elite can become gods, live in paradise, and be served by robots or ‘downgraded’ humans) agenda.

This is a perfect example of how the media is used to propagandize us. Write a garbage book, have your other tribesmen promote it, pat you on the back, etc.

Further Reading

-

Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality

-

Donna Haraway’s ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’.

-

In September 2013 two Oxford researchers, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, published ‘The Future of Employment’, in which they surveyed the likelihood of different professions being taken over by computer algorithms within the next twenty years.

Exceptional Excepts

The writing is on the wall: equality is out – immortality is in.

family structure, marriages and child–parent relationships would be transformed.

modern humanist education believes in teaching students to think for themselves.

Table of Contents

- 01: The New Human Agenda

- 02: The Anthropocene

- 03: The Human Spark

- 04: The Storytellers

- 05: The Odd Couple

- 06: The Modern Covenant

- 07: The Humanist Revolution

- 08: The Time Bomb in the Laboratory

- 09: The Great Decoupling

- 10: The Ocean of Consciousness

- 11: The Data Religion

Part 1: Homo sapiens Conquerers the World

Part 2: Homo sapiens Gives Meaning to the World

Part 3: Homo sapiens Lose Control

- Pages numbers from the pdf.

· 01: The New Human Agenda

page 7:

-

Let’s start with famine, which for thousands of years has been humanity’s worst enemy. Until recently most humans lived on the very edge of the biological poverty line, below which people succumb to malnutrition and hunger. A small mistake or a bit of bad luck could easily be a death sentence for an entire family or village.

-

Yet somehow art, culture, and a plethora of other things that can only occur with time, time not spent scraping by, to invent them.

page 17:

-

Mentions logic bombs originating in Iran and N. Korea that could blow up California’s facilities. Conveniently ignores the NSA developed and Mossad modified Stuxnet. Wait, this guy is a Jew? Whoda thunk it.

-

The gun [nuclear bombs] that appeared in the first act of the Cold War was never fired.

-

It appeared at the end of WW2 and it was fired, at least twice.

page 18:

-

terrorism is a show. Terrorists stage a terrifying spectacle of violence that captures our imagination and makes us feel as if we are sliding back into medieval chaos.

-

One one hand I agree, but, if it wasn’t for the media magnifying terrorism, I wouldn’t even know about it. Who is the real terrorist then?

page 20:

-

The most common reaction of the human mind to achievement is not satisfaction, but craving for more.

-

we will now aim to upgrade humans into gods,

page 22:

-

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights does not say that humans have ‘the right to life until the age of ninety’. It says that every human has a right to life, period.

-

Notable examples are the gerontologist Aubrey de Grey and the polymath and inventor Ray Kurzweil

-

In 2012 Kurzweil was appointed a director of engineering at Google, and a year later Google launched a sub-company called Calico whose stated mission is ‘to solve death’.26 Google has recently appointed another immortality true-believer, Bill Maris, to preside over the Google Ventures investment fund. In a January 2015 interview, Maris said, ‘If you ask me today, is it possible to live to be 500, the answer is yes.’ Maris backs up his brave words with a lot of hard cash. Google Ventures is investing 36 per cent of its $2 billion portfolio in life sciences start-ups, including several ambitious life-extending projects.

-

PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel has recently confessed that he aims to live for ever.

page 23:

-

The writing is on the wall: equality is out – immortality is in.

-

In the twentieth century we have almost doubled life expectancy from forty to seventy

-

That is because so many children died; they dragged the average down. He admits this a few pages earlier! Go-go gadget sophistry!

- family structure, marriages and child–parent relationships would be transformed.

page 24:

-

In 1900 global life expectancy was no higher than forty because many people died young from malnutrition, infectious diseases and violence.

-

In truth, so far modern medicine hasn’t extended our natural life span by a single year. Its great achievement has been to save us from premature death

page 26:

-

Without government planning, economic resources and scientific research, individuals will not get far in their quest for happiness. If your country is torn apart by war, if the economy is in crisis and if health care is non-existent, you are likely to be miserable.

-

Schools were founded to produce skillful and obedient citizens who would serve the nation loyally.

page 32:

- increasing numbers of schoolchildren take stimulants such as Ritalin. In 2011, 3.5 million American children were taking medications for ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). In the UK the number rose from 92,000 in 1997 to 786,000 in 2012.38

page 33:

- And drugs are just the beginning. In research labs experts are already working on more sophisticated ways of manipulating human biochemistry, such assending direct electrical stimuli to appropriate spots in the brain

page 34:

-

To attain real happiness, humans need to slow down the pursuit of pleasant sensations, not accelerate it.

-

It will be necessary to change our biochemistry and re-engineer our bodies and minds. So we are working on that. You may debate whether it is good or bad, but it seems that the second great project of the twenty-first century – to ensure global happiness – will involve re engineering Homo sapiens so that it can enjoy everlasting pleasure.

page 36:

- In early 2015 several hundred workers in the Epicenter high-tech hub in Stockholm had microchips implanted into their hands. The chips are about the size of a grain of rice and store personalised security information that enables workers to open doors and operate photocopiers with a wave of their hand. Soon they hope to make payments in the same way.

page 40:

- If growth ever stops, the economy won’t settle down to some cosy equilibrium; it will fall to pieces.

page 42:

- Healing is the initial justification for every upgrade. Find some professors experimenting in genetic engineering or brain–computer interfaces, and ask them why they are engaged in such research. In all likelihood they would reply that they are doing it to cure disease.

page 45:

-

our world was created by an accidental chain of events,

-

Movements seeking to change the world often begin by rewriting history, thereby enabling people to reimagine the future. Whether you want workers to go on a general strike, women to take possession of their bodies, or oppressed minorities to demand political rights – the first step is to retell their history.

Part 1: Homo sapiens Conquerers the World

· 02: The Anthropocene

page 63:

- This is the basic lesson of evolutionary psychology: a need shaped thousands of generations ago continues to be felt subjectively even if it is no longer necessary for survival and reproduction in the present.

page 67:

-

In the wild, piglets, calves and puppies that fail to bond with their mothers rarely survive for long. Until recently that was true of human children too.

-

What changed?

- John Watson, a leading childcare authority in the 1920s, sternly advised parents, ‘Never hug and kiss [your children], never let them sit in your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say goodnight. Shake hands with them in the morning.’ 22 The popular magazine Infant Care explained that the secret of raising children is to maintain discipline and to provide the children’s material needs according to a strict daily schedule. A 1929 article instructed parents that if an infant cries out for food before the normal feeding time, ‘Do not hold him, nor rock him to stop his crying, and do not nurse him until the exact hour for the feeding comes. It will not hurt the baby, even the tiny baby, to cry.’23

page 68:

- Harry Harlow separated infant monkeys from their mothers shortly after birth, and isolated them in small cages. When given a choice between a metal dummy-mother fitted with a milk bottle, and a soft cloth-covered dummy with no milk, the baby monkeys clung to the barren cloth mother for all they were worth.

· 03: The Human Spark

page 81:

- scientists can even induce feelings of anger or love by electrically stimulating the right neurons.

page 82:

-

Anger is an extremely concrete experience… When I say, ‘I am angry!’ I am pointing to a very tangible feeling.

-

Tangible? Maybe. Concrete? No.

page 86:

- Maybe the mind should join the soul, God and ether in the dustbin of science?

page 89:

- For all you know, the year might be 2216 and you are a bored teenager immersed inside a ‘virtual world’ game that simulates the primitive and exciting world of the early twenty-first century. Once you acknowledge the mere feasibility of this scenario, mathematics leads you to a very scary conclusion: since there is only one real world, whereas the number of potential virtual worlds is infinite, the probability that you happen to inhabit the sole real world is almost zero.

page 98:

-

Throughout history, disciplined armies easily routed disorganised hordes, and unified elites dominated the disorderly masses.

-

Indeed, much of the elite’s efforts focused on ensuring that the 180 million people at the bottom would never learn to cooperate.

- if you want to launch a revolution, don’t ask yourself, ‘how many people support my ideas?’ instead, ask yourself, ‘how many of my supporters are capable of effective collaboration?’ the russian revolution finally erupted not when 180 million peasants rose against the tsar, but rather when a handful of communists placed themselves at the right place at the right time. in 1917, at a time when the russian upper and middle classes numbered at least 3 million people, the communist party had just 23,000 members. 19 the communists nevertheless gained control of the vast russian empire because they organised themselves well.

page 103:

- Among pygmy chimpanzees – also known as bonobos – things are a bit different. Bonobos often use sex in order to dispel tensions and cement social bonds. Not surprisingly, homosexual intercourse is consequently very common among them.

Part 2: Homo sapiens Gives Meaning to the World

· 04: The Storytellers

page 114:

- Humans think they make history, but history actually revolves around the web of stories.

· 05: The Odd Couple

page 143:

- Sam Harris.

· 06: The Modern Covenant

page 148:

-

The cycle was eventually broken in the modern age thanks to people’s growing trust in the future, and the resulting miracle of credit. Credit is the economic manifestation of trust.

-

Evolutionary pressures have accustomed humans to see the world as a static pie. If somebody gets a bigger slice of the pie, somebody else inevitably gets a smaller slice.

-

Modernity, in contrast, is based on the firm belief that economic growth is not only possible but is absolutely essential.

-

This fundamental dogma can be summarized in one simple idea: ‘If you have a problem, you probably need more stuff, and in order to have more stuff, you must produce more of it.’

-

The ‘stuff’ all comes from earth. Earth is finite. Period. The more iron I mine, the less iron there is for everyone else to mine.

page 151:

- The credo of ‘more stuff’ accordingly urges individuals, firms and governments to discount anything that might hamper economic growth, such as preserving social equality, ensuring ecological harmony or honouring your parents.

page 152:

-

social structures and traditional values that stand in the way of free-market capitalism are destroyed and dismantled.

-

Take, for example, a software engineer making $250 per hour working for some hi tech start-up. One day her elderly father has a stroke. He now needs help with shopping, cooking and even showering. She could move her father to her own house, leave home later in the morning, come back earlier in the evening and take care of her father personally. Both her income and the start-up’s productivity would suffer, but her father would enjoy the care of a respectful and loving daughter. Alternatively, the engineer could hire a Mexican carer who, for $25 per hour, would live with the father and provide for all his needs. That would mean business as usual for the engineer and her start-up, and even the carer and the Mexican economy would benefit. What should the engineer do?

-

This kind of inflation irks me. Software engineer making $250 per hour is absurd even in Silly Con Valley, but at a start-up? And she’s a she? Wholly unrealistic.

-

If economic growth demands that we loosen family bonds, encourage people to live away from their parents, and import carers from the other side of the world – so be it.

-

humans can discover new materials and sources of energy.

-

While humans might discover new materials, MAYBE, what is more accurate to say is humans can synthesize new materials FROM EXISTING MATERIALS. At the end of the day, we are stuck with what is on earth. Sure, you can turn oil into plastic, but you are unlikely to discover unobtanium deposits that revolutionize industry. Similarly, we might find ways of extracting energy from existing materials, but we aren’t going to find new SOURCES.

page 154:

-

The traditional view of the world as a pie of a fixed size presupposes there are only two kinds of resources in the world: raw materials and energy. But in truth, there are three kinds of resources: raw materials, energy and knowledge. Raw materials and energy are exhaustible – the more you use, the less you have. Knowledge, in contrast, is a growing resource – the more you use, the more you have.

-

How much knowledge do I need to build a log cabin, without logs? Knowledge, while infinite in theory, can only manipulate what exists already.

-

Indeed, when you increase your stock of knowledge, it can give you more raw materials and energy as well. If I invest $100 million searching for oil in Alaska and I find it, then I now have more oil, but my grandchildren will have less of it. In contrast, if I invest $100 million researching solar energy, and I find a new and more efficient way of harnessing it, then both I and my grandchildren will have more energy.

-

What are we building the panels out of? Whatever it is, it is limited by the amount on earth.

page 157:

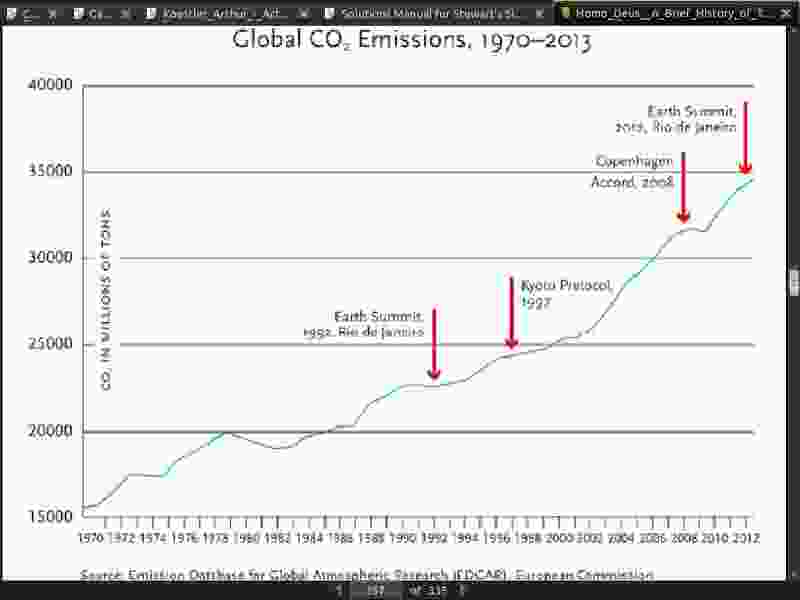

- The dip in emissions circa 2008-9 was from the global financial crisis.

page 158:

- Whereas previously social and political systems endured for centuries, today every generation destroys the old world and builds a new one in its place. As the Communist Manifesto brilliantly put it, the modern world positively requires uncertainty and disturbance. All fixed relations and ancient prejudices are swept away, and new structures become antiquated before they can ossify.

· 07: The Humanist Revolution

page 161:

-

God’s death did not lead to social collapse.

-

God isn’t dead to the vast majority of the world.

- those who pose the greatest threat to global law and order are precisely those people who continue to believe in God and His all encompassing plans. God-fearing Syria is a far more violent place than the atheist Netherlands.

page 163:

-

Jean-Jacques Rousseau summed it all up in his novel Émile, the eighteenth-century bible of feeling. Rousseau held that when looking for the rules of conduct in life, he found them ‘in the depths of my heart, traced by nature in characters which nothing can efface. I need only consult myself with regard to what I wish to do; what I feel to be good is good, what I feel to be bad is bad.’1

-

Accordingly, when a modern woman wants to understand the meaning of an affair she is having, she is far less prone to blindly accept the judgements of a priest or an ancient book. Instead, she will carefully examine her feelings. If her feelings aren’t very clear, she will call a good friend, meet for coffee and pour out her heart. If things are still vague, she will go to her therapist, and tell him all about it.

-

True, the therapist’s bookshelf sags under the weight of Freud, Jung and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Yet these are not holy scriptures. The DSM diagnoses the ailments of life, not the meaning of life.

- if the very same feelings that once drove you into the arms of one man now drive you into the arms of another, what’s wrong with that? If an extramarital affair provides an outlet for emotional and sexual desires that are not satisfied by your spouse of twenty years, and if your new lover is kind, passionate and sensitive to your needs – why not enjoy it?

page 164:

-

If two adult men enjoy having sex with one another, and they don’t harm anyone while doing so, why should it be wrong, and why should we outlaw it? It is a private matter between these two men, and they are free to decide about it according to their inner feelings.

-

Until it spills over into every aspect of life. On TV, on police cars, in pride parades, on LGBT tolerant signs in parks… when it stops being private is when we should outlaw it. Or rather, outlaw the excessive public displays. If not, I want you to tolerate my KKK pride parade.

-

every year for the past decade the Israeli LGBT community holds a gay parade in the streets of Jerusalem. It is a unique day of harmony in this conflict-riven city, because it is the one occasion when religious Jews, Muslims and Christians suddenly find a common cause – they all fume in accord against the gay parade. What’s really interesting, though, is the argument they use. They don’t say, ‘You shouldn’t hold a gay parade because God forbids homosexuality.’ Rather, they explain to every available microphone and TV camera that ‘seeing a gay parade passing through the holy city of Jerusalem hurts our feelings. Just as gay people want us to respect their feelings, they should respect ours.’

-

And? Isn’t that simply the same thing the LGBT want? We have to tolerate their parades, but when I call them fags it is a hate crime? Tolerance is a two-way street.

page 165:

-

We believe that the voter knows best, and that the free choices of individual humans are the ultimate political authority.

-

Ignore the oligarchy behind the curtain. Your vote matters!

-

In order to get in touch with my feelings, I need to filter out the empty propaganda slogans, the endless lies of ruthless politicians, the distracting noise created by cunning spin doctors, and the learned opinions of hired pundits. I need to ignore all this racket, and attend only to my authentic inner voice.

-

Like this very book?!

page 167:

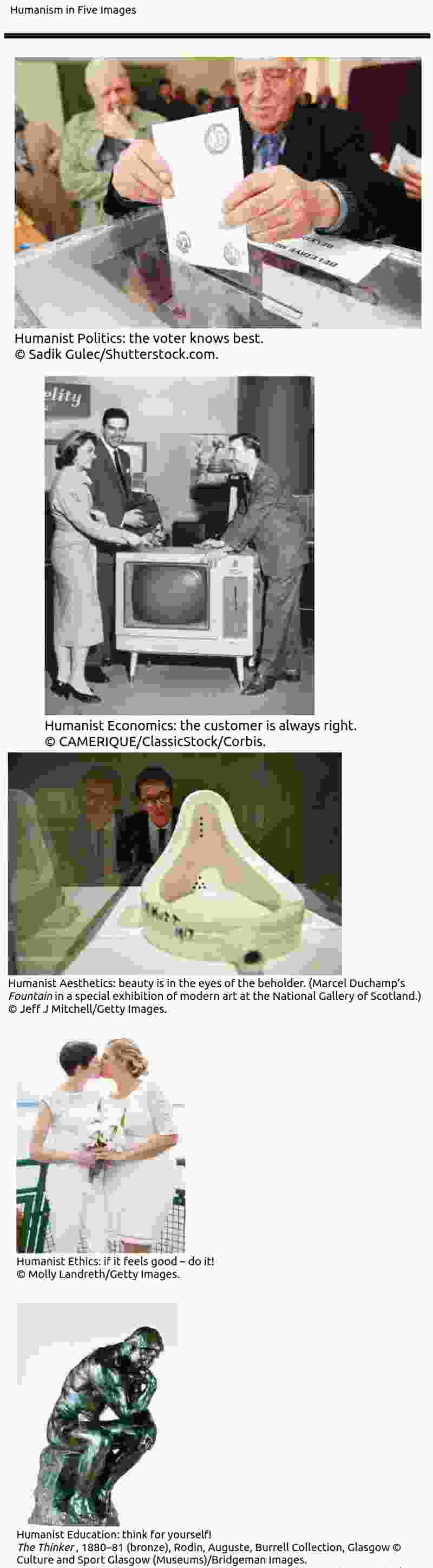

- In ethics, the humanist motto is ‘if it feels good – do it’. In politics, humanism instructs us that ‘the voter knows best’. In aesthetics, humanism says that ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’.

page 168:

-

In a free market, the customer is always right. If customers don’t want it, it means that it is not a good car. … Nobody has the authority to tell customers that they are wrong, and heaven forbid that a government would try to force citizens to buy a particular car against their will. What’s true of cars is true of all other products.

-

Except insurance.

-

Listen, for example, to Professor Leif Andersson from the University of Uppsala. He specialises in the genetic enhancement of farm animals, in order to create faster-growing pigs, dairy cows that produce more milk, and chickens with extra meat on their bones. In an interview for the newspaper Haaretz, reporter Naomi Darom confronted Andersson with the fact that such genetic manipulations might cause much suffering to the animals. Already today ‘enhanced’ dairy cows have such heavy udders that they can barely walk, while ‘upgraded’ chickens cannot even stand up. Professor Andersson had a firm answer: ‘Everything comes back to the individual customer and to the question how much the customer is willing to pay for meat . . . we must remember that it would be impossible to maintain current levels of global meat consumption without the [enhanced] modern chicken . . . if customers ask us only for the cheapest meat possible – that’s what the customers will get . . . Customers need to decide what is most important to them – price, or something else.’3

-

If millions of people freely choose to buy the company’s products, who are you to tell them that they are wrong?

-

How does this apply to Lockheed and like ilk? Are millions of consumers buying missiles?

page 170:

page 172:

- modern humanist education believes in teaching students to think for themselves.

page 182:

-

The more liberty individuals enjoy, the more beautiful, rich and meaningful is the world. Due to this emphasis on liberty, the orthodox branch of humanism is known as ‘liberal humanism’ or simply as ‘liberalism’. *

-

It is liberal politics that believes the voter knows best. Liberal art holds that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Liberal economics maintains that the customer is always right. Liberal ethics advises us that if it feels good, we should go ahead and do it. Liberal education teaches us to think for ourselves, because we will find all the answers within us.

page 183:

-

Holding democratic elections won’t help, because then the question will be who would get to vote in these elections – only German citizens, or also millions of Asians and Africans who want to immigrate to Germany? Why privilege the feelings of one group over another? Likewise, you cannot resolve the Arab–Israeli conflict by making 8 million Israeli citizens and 350 million citizens of Arab League nations vote on it. For obvious reasons, the Israelis won’t feel committed to the outcome of such a plebiscite.

-

I don’t understand. How do people from thousands of miles away voting in a German election and Israel and it’s neighbors voting compare? Israel won’t stand for majority rule in the region. It is at least reasonable to have the Arab and Israel states vote, they are neighbors. Why would Palestinians ever vote in Germany? And further, why would Israel not be committed to rule by majority vote? Oh, they are the chose people, duh!

page 184:

-

Global peace will be achieved not by celebrating the distinctiveness of each nation, but by unifying all the workers of the world; and social harmony won’t be achieved by each person narcissistically exploring their own inner depths, but rather by each person prioritising the needs and experiences of others over their own desires.

-

A liberal may reply that by exploring her own inner world she develops her compassion and her understanding of others, but such reasoning would have cut little ice with Lenin or Mao. They would have explained that individual self exploration is a bourgeois indulgent vice, and that when I try to get in touch with my inner self, I am all too likely to fall into one or another capitalist trap.

page 185:

- Evolutionary humanism has a different solution to the problem of conflicting human experiences. Rooting itself in the firm ground of Darwinian evolutionary theory, it says that conflict is something to applaud rather than lament. Conflict is the raw material of natural selection, which pushes evolution forward. Some humans are simply superior to others, and when human experiences collide, the fittest humans should steamroll everyone else. The same logic that drives humankind to exterminate wild wolves and to ruthlessly exploit domesticated sheep also mandates the oppression of inferior humans by their superiors. It’s a good thing that Europeans conquer Africans and that shrewd businessmen drive the dim-witted to bankruptcy. If we follow this evolutionary logic, humankind will gradually become stronger and fitter, eventually giving rise to superhumans.

page 186:

- Who exactly are these superior humans who herald the coming of the superman? They might be entire races, particular tribes or exceptional individual geniuses. In any case, what makes them superior is that they have better abilities, manifested in the creation of new knowledge, more advanced technology, more prosperous societies or more beautiful art.

page 188:

- Just as Stalin’s gulags do not automatically nullify every socialist idea and argument, so too the horrors of Nazism should not blind us to whatever insights evolutionary humanism might offer.

page 194:

- Liberal democracy was saved only by nuclear weapons. NATO adopted the doctrine of MAD (mutual assured destruction), according to which even conventional Soviet attacks would be answered by an all-out nuclear strike. ‘If you attack us,’ threatened the liberals, ‘we will make sure nobody comes out of it alive.’ Behind this monstrous shield, liberal democracy and the free market managed to hold out in their last bastions, and Westerners could enjoy sex, drugs and rock and roll, as well as washing machines, refrigerators and televisions. Without nukes, there would have been no Woodstock, no Beatles and no overflowing supermarkets.

page 196:

-

Nobody seems to know what the Chinese believe these days – including the Chinese themselves. In theory China is still communist, but in practice it is nothing of the kind. Some Chinese thinkers and leaders toy with a return to Confucianism, but that’s hardly more than a convenient veneer. This ideological vacuum makes China the most promising breeding ground for the new techno-religions emerging from Silicon Valley

-

More than a century after Nietzsche pronounced Him dead, God seems to be making a comeback. But this is a mirage. God is dead – it just takes a while to get rid of the body.

-

What will happen to the job market once artificial intelligence outperforms humans in most cognitive tasks? What will be the political impact of a massive new class of economically useless people? What will happen to relationships, families and pension funds when nanotechnology and regenerative medicine turn eighty into the new fifty? What will happen to human society when biotechnology enables us to have designer babies, and to open unprecedented gaps between rich and poor?

page 197:

- True, hundreds of millions may nevertheless go on believing in Islam, Christianity or Hinduism. But numbers alone don’t count for much in history. History is often shaped by small groups of forward-looking innovators rather than by the backward looking masses.

page 198:

-

When we think of nineteenth-century visionaries, we are far more likely to recall Marx, Engels and Lenin than the Mahdi, Pius IX or Hong Xiuquan.

-

If you count on national health services, pension funds and free schools, you need to thank Marx and Lenin (and Otto von Bismarck) far more than Hong Xiuquan or the Mahdi.

-

Thanks for the dependency and indoctrination! The individuals in the liberal paradise of individualism can’t even take care of themselves.

page 199:

- In the early twenty-first century the train of progress is again pulling out of the station – and this will probably be the last train ever to leave the station called Homo sapiens. Those who miss this train will never get a second chance. In order to get a seat on it, you need to understand twenty-first-century technology, and in particular the powers of biotechnology and computer algorithms. These powers are far more potent than steam and the telegraph, and they will not be used merely for the production of food, textiles, vehicles and weapons. The main products of the twenty-first century will be bodies, brains and minds, and the gap between those who know how to engineer bodies and brains and those who do not will be far bigger than the gap between Dickens’s Britain and the Mahdi’s Sudan. Indeed, it will be bigger than the gap between Sapiens and Neanderthals. In the twenty-first century, those who ride the train of progress will acquire divine abilities of creation and destruction, while those left behind will face extinction.

page 200:

- If Marx came back to life today, he would probably urge his few remaining disciples to devote less time to reading Das Kapital and more time to studying the Internet and the human genome.

page 202:

- What, then, will happen once we realise that customers and voters never make free choices, and once we have the technology to calculate, design or outsmart their feelings? If the whole universe is pegged to the human experience, what will happen once the human experience becomes just another designable product, no different in essence from any other item in the supermarket?

Part 3: Homo sapiens Lose Control

· 08: The Time Bomb in the Laboratory

page 208:

- Doubting free will is not just a philosophical exercise. It has practical implications. If organisms indeed lack free will, it implies we could manipulate and even control their desires using drugs, genetic engineering or direct brain stimulation. If you want to see philosophy in action, pay a visit to a robo-rat laboratory. A robo rat is a run-of-the-mill rat with a twist: scientists have implanted electrodes into the sensory and reward areas in the rat’s brain. This enables the scientists to manoeuvre the rat by remote control. After short training sessions, researchers have managed not only to make the rats turn left or right, but also to climb ladders, sniff around garbage piles, and do things that rats normally dislike, such as jumping from great heights. Armies and corporations show keen interest in the robo-rats, hoping they could prove useful in many tasks and situations. For example, robo-rats could help detect survivors trapped under collapsed buildings, locate bombs and booby traps, and map underground tunnels and caves.

page 209:

- Due to obvious ethical restrictions, researchers implant electrodes into human brains only under special circumstances. Hence most relevant experiments on humans are conducted using non-intrusive helmet-like devices (technically known as ‘transcranial direct current stimulators’). The helmet is fitted with electrodes that attach to the scalp from outside. It produces weak electromagnetic fields and directs them towards specific brain areas, thereby stimulating or inhibiting select brain activities.

page 213:

-

It’s as if the CIA conducts a drone strike in Pakistan, unbeknown to the US State Department. When a journalist grills State Department officials about it, they make up some plausible explanation. In reality, the spin doctors don’t have a clue why the strike was ordered, so they just invent something. A similar mechanism is employed by all human beings, not just by split-brain patients. Again and again my own private CIA does things without the approval or knowledge of my State Department, and then my State Department cooks up a story that presents me in the best possible light. Often enough, the State Department itself becomes convinced of the pure fantasies it has invented.14

-

What an analogy!

page 221:

- Every moment, the biochemical mechanisms of the brain create a flash of experience, which immediately disappears. Then more flashes appear and fade, appear and fade, in quick succession. These momentary experiences do not add up to any enduring essence. The narrating self tries to impose order on this chaos by spinning a never ending story, in which every such experience has its place, and hence every experience has some lasting meaning. But, as convincing and tempting as it may be, this story is a fiction.

· 09: The Great Decoupling

page 223:

-

(1) Humans will lose their economic and military usefulness, hence the economic and political system will stop attaching much value to them.

-

(2) The system will still find value in humans collectively, but not in unique individuals.

-

(3) The system will still find value in some unique individuals, but these will be a new elite of upgraded superhumans rather than the mass of the population.

page 224:

-

Thus Charles W. Eliot, president of Harvard from 1869 to 1909, wrote on 5 August 1917 in the New York Times that ‘democratic armies fight better than armies aristocratically organised and autocratically governed’ and that ‘the armies of nations in which the mass of the people determine legislation, elect their public servants, and settle questions of peace and war, fight better than the armies of an autocrat who rules by right of birth and by commission from the Almighty’. 2

-

A similar rationale stood behind the enfranchisement of women in the wake of the First World War. Realising the vital role of women in total industrial wars, countries saw the need to give them political rights in peacetime. Thus in 1918 President Woodrow Wilson became a supporter of women’s suffrage, explaining to the US Senate that the First World War ‘could not have been fought, either by the other nations engaged or by America, if it had not been for the services of women – services rendered in every sphere – not only in the fields of effort in which we have been accustomed to see them work, but wherever men have worked and upon the very skirts and edges of the battle itself. We shall not only be distrusted but shall deserve to be distrusted if we do not enfranchise them with the fullest possible enfranchisement.’3

-

Another coincidence that stems from another artificial war. WW1 and 2, I think, were the spearhead to bring about the change in the world we see today. Break up families, introduce technological change, etc. Cultural Patterns and Technical Change; it only gets more apropos the more I learn.

page 225:

- Over the last decades there has been an immense advance in computer intelligence, but there has been exactly zero advance in computer consciousness.

page 234:

-

As algorithms push humans out of the job market, wealth might become concentrated in the hands of the tiny elite that owns the all-powerful algorithms, creating unprecedented social inequality.

-

If the algorithm makes the right decisions, it could accumulate a fortune, which it could then invest as it sees fit, perhaps buying your house and becoming your landlord. If you infringe on the algorithm’s legal rights – say, by not paying rent – the algorithm could hire lawyers and sue you in court. If such algorithms consistently outperform human fund managers, we might end up with an algorithmic upper class owning most of our planet.

-

How does the algorithm accumulate a fortune… for itself. If I create it, don’t I own it? Would the creator somehow give up their rights, and decree an algorithm sovereign?

page 236:

-

In September 2013 two Oxford researchers, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, published ‘The Future of Employment’, in which they surveyed the likelihood of different professions being taken over by computer algorithms within the next twenty years. The algorithm developed by Frey and Osborne to do the calculations estimated that 47 per cent of US jobs are at high risk. For example, there is a 99 per cent probability that by 2033 human telemarketers and insurance underwriters will lose their jobs to algorithms. There is a 98 per cent probability that the same will happen to sports referees, 97 per cent that it will happen to cashiers and 96 per cent to chefs. Waiters – 94 per cent. Paralegal assistants – 94 per cent. Tour guides – 91 per cent. Bakers – 89 per cent. Bus drivers – 89 per cent. Construction labourers – 88 per cent. Veterinary assistants – 86 per cent. Security guards – 84 per cent. Sailors – 83 per cent. Bartenders – 77 per cent. Archivists – 76 per cent. Carpenters – 72 per cent. Lifeguards – 67 per cent.

-

The technological bonanza will probably make it feasible to feed and support the useless masses even without any effort on their side. But what will keep them occupied and content? People must do something, or they will go crazy. What will they do all day? One solution might be offered by drugs and computer games.

page 244:

- I could have saved myself from such a fate if I only authorized Google to vote for me.

page 246:

- In the twenty-first century our personal data is probably the most valuable resource most humans still have to offer, and we are giving it to the tech giants in exchange for email services and funny cat videos.

page 249:

- The third threat to liberalism is that some people will remain both indispensable and undecipherable, but they will constitute a small and privileged elite of upgraded humans. These superhumans will enjoy unheard-of abilities and unprecedented creativity, which will allow them to go on making many of the most important decisions in the world. They will perform crucial services for the system, while the system could not understand and manage them. However, most humans will not be upgraded, and they will consequently become an inferior caste, dominated by both computer algorithms and the new superhumans.

· 10: The Ocean of Consciousness

page 254:

- This idea is an updated variant on the old dreams of evolutionary humanism, which already a century ago called for the creation of superhumans. However, whereas Hitler and his ilk planned to create superhumans by means of selective breeding and ethnic cleansing, twenty-first-century techno-humanism hopes to reach the goal far more peacefully, with the help of genetic engineering, nanotechnology and brain–computer interfaces.

page 262:

- The humanist recommendation to listen to ourselves has ruined the lives of many a person, whereas the right dosage of the right chemical has greatly improved the well-being and relationships of millions.

· 11: The Data Religion

page 265:

- Dataists are sceptical about human knowledge and wisdom, and prefer to put their trust in Big Data and computer algorithms.

page 266:

- experts see the economy as a mechanism for gathering data about desires and abilities, and turning this data into decisions. According to this view, free-market capitalism and state-controlled communism aren’t competing ideologies, ethical creeds or political institutions. At bottom, they are competing data-processing systems. Capitalism uses distributed processing, whereas communism relies on centralised processing.

page 271:

- Some people believe that there is somebody in charge after all. Not democratic politicians or autocratic despots, but rather a small coterie of billionaires who secretly run the world. But such conspiracy theories never work, because they underestimate the complexity of the system. A few billionaires smoking cigars and drinking Scotch in some back room cannot possibly understand everything happening on the globe, let alone control it. Ruthless billionaires and small interest groups flourish in today’s chaotic world not because they read the map better than anyone else, but because they have very narrow aims. In a chaotic system, tunnel vision has its advantages, and the billionaires’ power is strictly proportional to their goals. If the world’s richest man would like to make another billion dollars he could easily game the system in order to achieve his goal. In contrast, if he would like to reduce global inequality or stop global warming, even he won’t be able to do it, because the system is far too complex.

page 276:

- People just want to be part of the data flow, even if that means giving up their privacy, their autonomy and their individuality.

page 277:

- What’s the point of doing or experiencing anything if nobody knows about it, and if it doesn’t contribute something to the global exchange of information?

page 284:

- In the past, censorship worked by blocking the flow of information. In the twenty-first century, censorship works by flooding people with irrelevant information. People just don’t know what to pay attention to, and they often spend their time investigating and debating side issues.