Home · Book Reports · 2018 · Git for Humans

- Author :: David Demaree

- Publication Year :: 2016

- Read Date :: 2018-08-15

- Source :: Git-for-Humans.pdf

designates my notes. / designates important.

Thoughts

This is an extremely short read. While it provided everything expected, it is still quite the crash course. There is enough to get you started, but that is all. You’ll need to follow up if you are doing more than the most basic of operations. That said, it was a great introduction to whet you appetite.

The book follows the typical introductory tech book format: first an explanation of version control is given, using a basic example of saving multiple copies of a file with different (dated) names. Git, as the author states multiple times, is simply a more complex, and powerful, way of doing just that.

Apparently Git also provides a very low level of abstraction and doesn’t hide much, which can be a blessing or a curse depending on your perspective. What is nice is that Git won’t do anything unless you explicitly tell it to.

From here it moves through the most basic commands: init, clone, status, add, and commit. These should cover most of your day-to-day use claims the author. With my minimal understanding of Git, using it only locally, I can mostly agree.

Next branches are covered, but it an high level fashion. There is no concrete tutorial like examples. Instead you get advice like: branches should, although there are no hard and fast rules, contain topics; you shouldn’t let your master and topic branches get too far apart; you should merge the master into topic or vice versa to keep them reasonably up to date.

That said, some teams use branches differently. One team may say: everything on master is deployable. Another might have release branches while master is cutting edge and less tested.

Merging is covered, also in high level detail. When merging a commit is made automatically, but you can override this to customize the message, but that is probably not necessary. The dreaded merge conflict and their resolution is touched on, again in high level.

Remote repositories are covered, but, like the other coverage, only in the most basic fashion. There is a good explanation of SSH and HTTPS remote access and there is a simple discussion of the basic remote commands: push, pull, fetch.

While it mentions that anyone can easily set up their own private remote, there are no details on how to do this. It does belabor that SSH will be read and write access, while HTTP can allow for only read access (or read/write).

Lastly how to look through the history with the log command is covered. Again, little detail beyond formatting is looked at.

Overall I’d say it is a worthwhile read, although there is nothing but the most basics here. If you want to learn more, there are several references to more detailed books and tutorials provided.

Further Reading

-

Scott Chacon’s excellent reference book Pro Git

-

Tim Pope’s “A Note About Git Commit Messages”

-

Chris Beams’s “How To Write A Git Commit Message”

-

Atlassian’s Git tutorials

Table of Contents

- Pages numbers from the actual book.

· 01: Thinking in Versions

· 02: Basics

· 03: Branches

page 54:

- you can tell git checkout to create and switch to a new branch at the same time by passing in the -b option, like so:

(master) $: git checkout -b new-homepage

Switched to a new branch 'new-homepage'

(new-homepage) $:

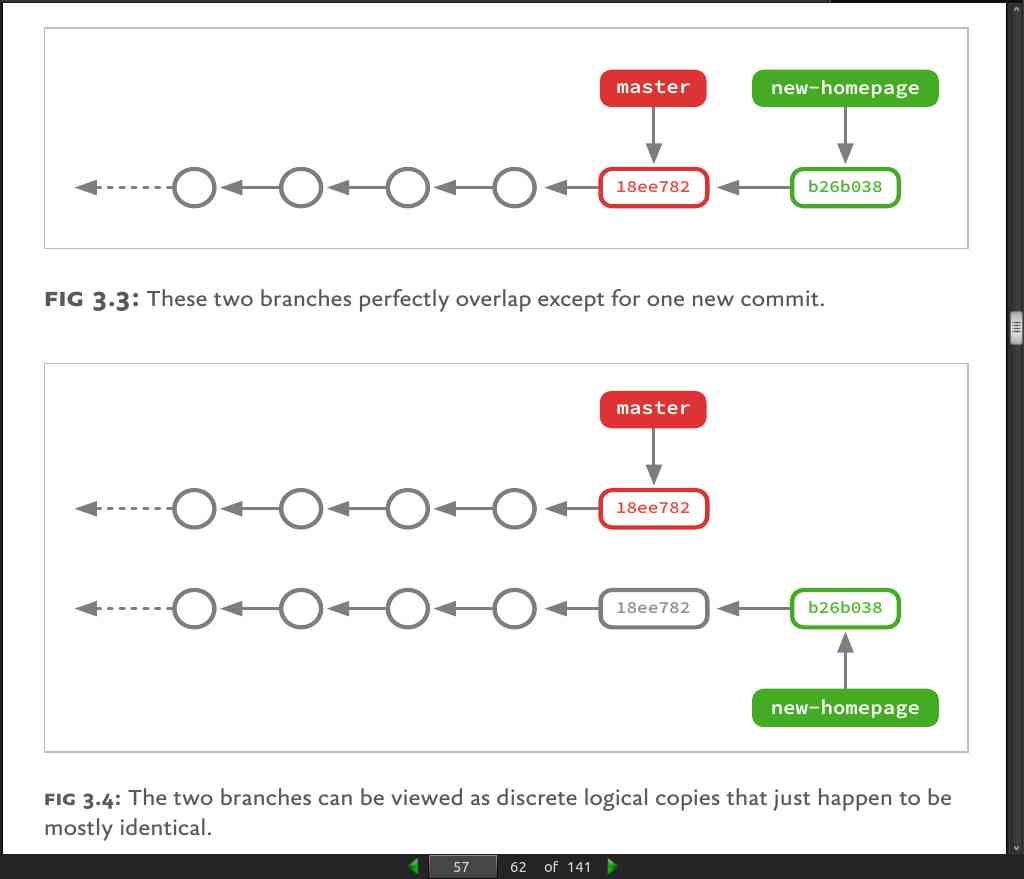

page 57:

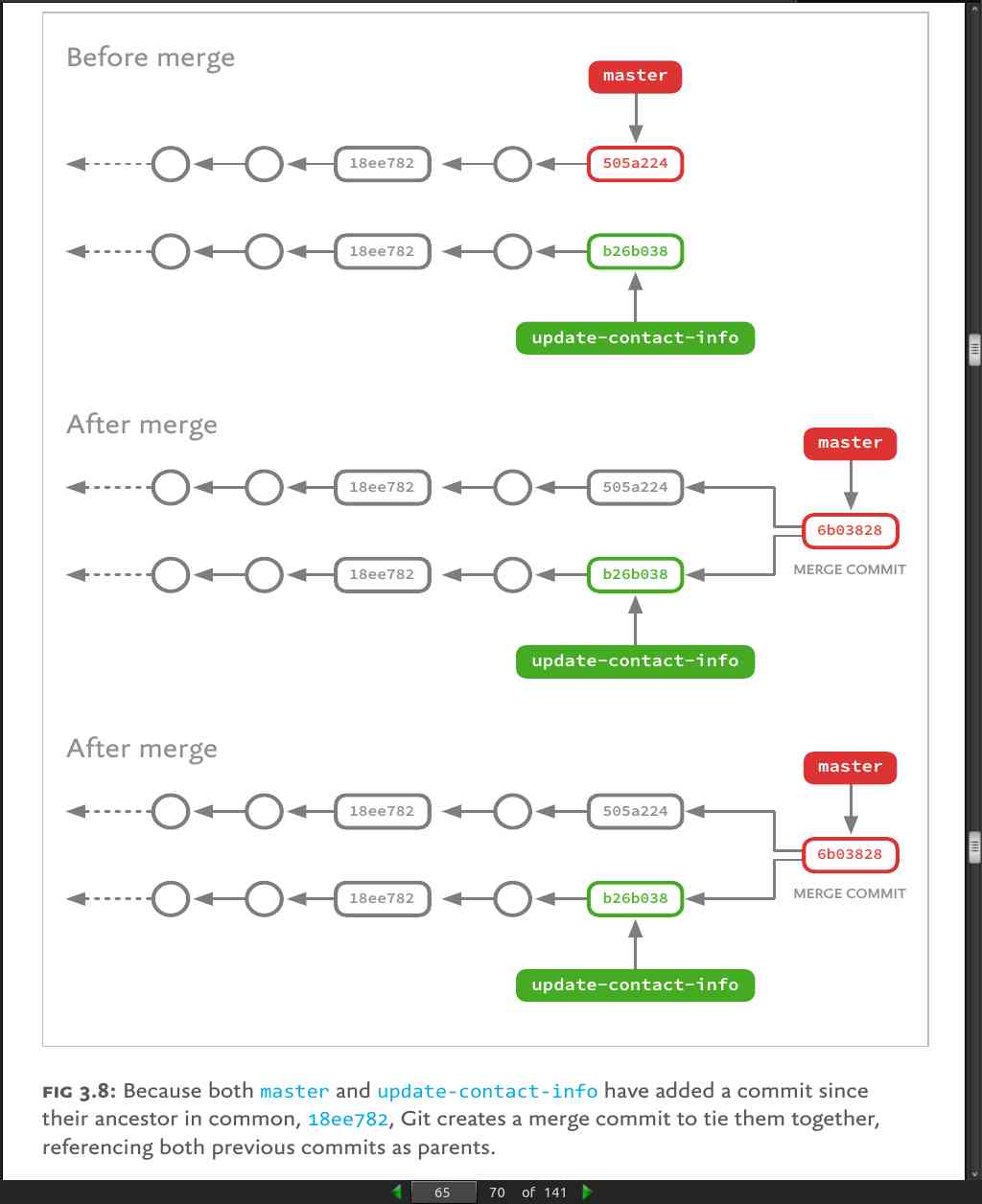

page 64:

- Once the merged snapshot has been automatically generated, by default Git seals the deal and commits it for you, with an automatically generated commit message: “Merge branch ‘update-contact-info’ into master.” This is only a default, of course: you can pass the –no-commit option to git merge to ask Git just to generate and stage the merged-together version of your work, but wait for you to commit it yourself. One reason you might do this is to craft your own commit message

page 65:

page 66:

- So, from time to time, you’ll want to merge new commits from master into your branch to bring it back up to date:

(new-homepage) $: git merge master

Updating c7038f8..1c4b16a

Fast-forward

Makefile | 7 ++

Rakefile | 15 ++--

- Ideally, the final state of each working branch should differ from master only in ways that are relevant to its topic.

page 70:

- The goal of keeping master and topic branches up to date with each other isn’t to prevent conflicts, but rather to make conflicts easier to manage by keeping the differences between two branches small.

· 04: Remotes

page 74:

- Server-side repos are what are called “bare” repos, consisting only of the actual repository data (old versions, branches) and no working copy (which also means no staging area). A directory containing a bare Git repo is usually marked by appending .git to its name,

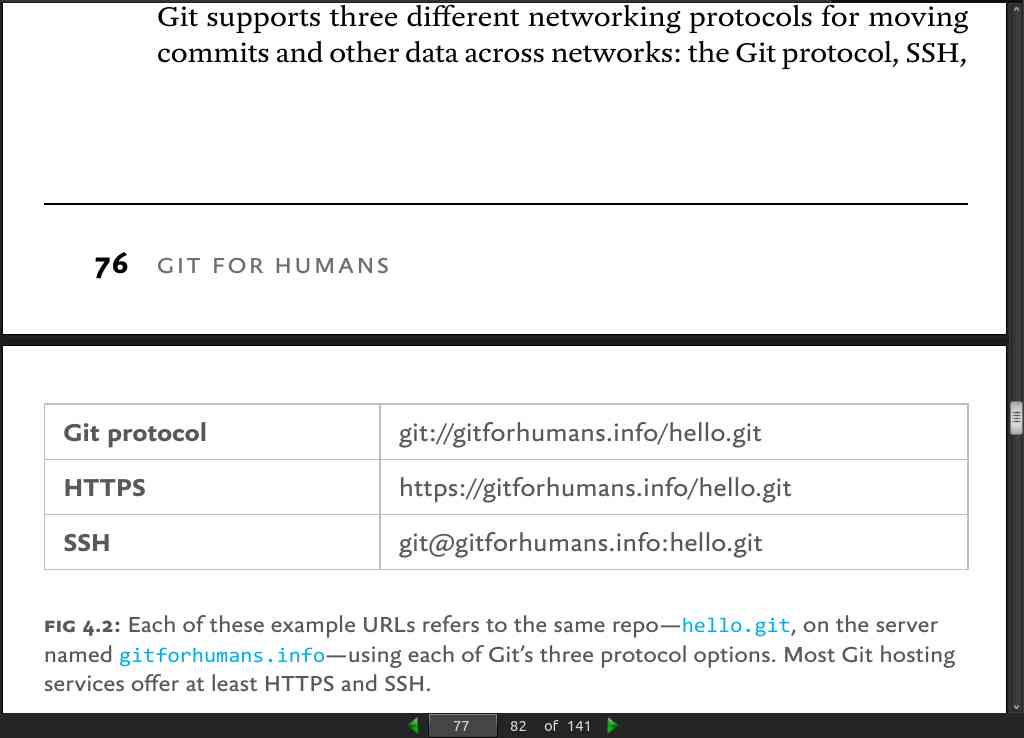

page 77:

-

Git’s SSH protocol is the exact same one many of us use to log in to remote servers every day. In fact, any SSH server you have access to can probably be used as a host for remote Git repositories. SSH remotes support both reading and writing, and you can use any authentication method SSH supports.

-

Whereas SSH must be private, and must allow read and write access to your repositories, HTTPS offers more flexibility. You can allow anyone on the internet to pull down changes from your repo, while restricting push access to members of your own team.

page 83:

- It’s important to remember that merging is implicitly part of pulling (and, for that matter, pushing). Or, to flip it around, it’s helpful to remember that both pushing and pulling are the remote form of merging. Both commands do the exact same job: they move a branch to another computer, then merge it into another branch.

page 86:

- always pull before you push to make sure your own local copy is up to date. There’s rarely any harm to pulling changes, and frequently lots of benefit.

page 87:

- The simplest way to set up a tracking relationship is to include the –set-upstream (or -u) option when invoking git push.

page 90:

-

Although by default the git branch command will only tell you what branches exist on your local copy, you can give it the –remote (-r) flag to ask it to instead show you all of the branches Git knows about from your remotes

-

git pull origin master is, in fact, just a shortcut for a git fetch, followed by git merge origin/master.

· 05: History

page 94:

- The –pretty option allowsyou to select from a number of predefined formats, or specify your own using a format string. Here’s the built-in oneline format, which shows only the commit ID and log message on a single line:

$: git log --pretty=oneline

45b1ec87cd2fde95a110dfe3028e93d25c9af186 Rename styles.css to main.css

bf8144d4690d3f6052dc7f42135e3e9944b96b5a Initial commit

page 95:

- This is best for seeing a list of what differs in a topic branch since we branched off. Here, we’ll ask git log to show all the commits that have been added to new-homepage that aren’t yet merged into master, using the –oneline option to make the log output easier to scan:

$: git log --oneline master..new-homepage

bce44eb Bigger navigation buttons

056c8fd Update hero area w/ new background image

7e53652 Make font loading async

-

Our range is listed here as start..end, or rather, olderbranch..newerbranch

-

The simplest way to explain what git log branch-a..branch-b does is that it shows you a list of all the commits in branch-b that aren’t in branch-a. In the previous example, we see three commits from new-homepage that aren’t yet merged into master.

-

What’s really cool is that we can ask git log to show us a list the other way around—to give us a list of commits in master that aren’t in new-homepage:

$: git log --oneline new-homepage..master

5514d53 Fix JavaScript bug on products page

4af326c Support for Microsoft Edge