Home · Book Reports · 2018 · Git Essentials

- Author :: Ferdinando Santacroce

- Publication Year :: 2015

- Read Date :: 2018-08-20

- Source :: Git-Essentials.pdf

designates my notes. / designates important.

Thoughts

From the introduction I thought this was going to be heavier; it talks about gaining a deep understanding of Git and that the book is more than a tutorial. I disagree. While there is enough to give you a very good understanding, none of it is difficult and I personally made my way though the book in a matter of a few days even following along by executing the tutorial.

That said, this is a great book to learn Git with. Everything is well explained and flows logically from topic to topic. It occasionally gets down in the grass and explains the underlying principles, but only occasionally. Most of the time it is straight forward, even to the point of repetitive. This occasional repetition is perfectly acceptable since you are, presumably, learning something new.

It starts off as you’d expect, with the install process for the big three operating systems. The main tutorial is presented from Windows, but through a bash emulator. It worked as described, flawlessly, on my Linux system.

Once installed, you set up a repo and then head to chapter 2.

In chapter 2 you set up another repo (practice practice practice) that will be used throughout most of the rest of the book. The concept used is a simple shopping list full of various fruits for the fruit salad you are planning to make.

There are many digressions in chapter 2 to explain some of the underlying concepts and functionality of Git. The first is the distinguishing of porcelain and plumbing commands. This analogy, thought up by Torvalds, refers to the clean, barely changing commands most users will be familiar with; the porcelain. Other, the plumbing, commands change more frequently but can be more powerful. While some plumbing commands are covered, you don’t really need to know them.

Next objects are discussed. Git has four objects: commits, trees, blobs, and annotated tags. Commits are, well commits! Trees you can think of as folders, blobs as files. Annotated tags are just that, tags.

When making commits, Git takes snapshots, not deltas, but if something is unchanged it is recycles. This means that multiple trees can point to the same (unchanged) blob.

Naturally branches come up next. These, being so important, are covered to a great extent. Navigating branches, with shortcuts like tilde and caret, and resetting branches are some of the more introductory topics.

Somewhat more advanced are the reglogs, which track (for 90 days by default) everything you do, are covered. These allow you to find hashes for old commits.

Tags, another way to mark your way path in your project, are mentioned. There is no hard and fast rules for tags; teams can use them as they see fit. There isn’t much to say, a tag is a tag!

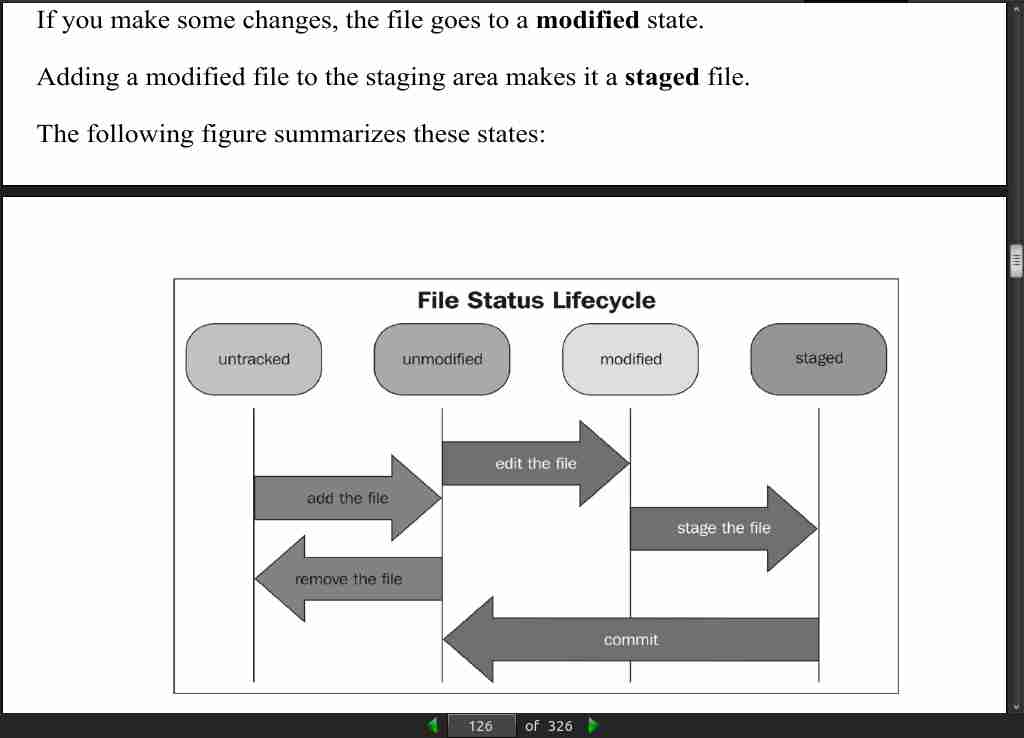

Next staging and unstaging, the nuts and bolts of getting ready to make customized and meaningful commits is covered.

Finally we get to merging, which is presented in such a way that makes it very approachable. Those without and understanding of merging may think it is voodoo magic, but this book shows you exactly how it works and how to easily navigate the dreaded merge conflict. Alternatively many tips are given so that you might avoid a conflict in the first place.

In the same vein, cherry-picking, which is somewhat more complicated, is covered. This is essentially taking bits and pieces from various commits on multiple branches and merging them into master (or wherever).

Basically this (long) chapter contains everything you need to know to work (locally) with Git.

Chapter three follows up with how to work, surprise, remotely! It follows the same path: setting up, making changes with pushes and pulls, and the GitHub specific forking and pull request.

Chapter four is more a tips and tricks chapter. Aliases, custom commands, can be created for Git in much the same way you can create aliases in bash.

A, somewhat tangential, tip lets you know that, while Git feels like a backup, you should not treat it as such. Always follow proper backup procedures, even when dealing with remote repositories. Although, the distributed nature of a shared project will provide you with a bit of extra insurance.

There are some tips on creating bare repositories, for example if you’ve been working locally but now want to share your project, and bundling to help share your project with non Git users.

Chapter five, after the initial technical understanding is absorbed, is probably the most important part of the book. It sets out to detail some best practices for things like committing and commit messages. Again, there are no hard and fast rules, and your team may have a policy in place when you arrive on a new project, but these are worth taking a good hard look at.

First, there should be only one change per commit. This makes it much simpler to see the log as a changelog one feature at a time, as well as increases the simplicity in cherry-picking.

To simplify the process of making commits, since you will likely do more than one change per day and often be pulled away into meetings and such, you can start, before writing or changing a single line of code, by scribbling down a list of all the tasks you need to accomplish. Next you can break them down into atomic bits. Keep breaking them down until it doesn’t feel natural to split them into smaller parts. This will be subjective. Then, write a single sentence that describes each of the parts. Bingo, you’ve got your commit messages pre-written. Now, just follow you plan. If you get pulled into a meeting, simply pick up where you left off later.

Chapter six, which I admittedly skim quickly, offers instruction for migrating from Subversion and a comparison of Git versus Subversion.

The last chapter, seven, includes a selection of various resources. There are a large number of GUI options, mostly for Windows, a personal web GUI to manage your self-hosted remote, several websites that offer tutorials, advice, or visualization, as well as a few links to cheatsheets.

Further Reading

-

https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/GitEssentialsSecondEdition_ColorImages.pdf

-

The Gitflow workflow: http://nvie.com/posts/a-successful-git-branching-model.

-

For more information on the Pomodoro Technique you can visit https://cirillocompany.de/pages/pomodoro-technique

-

Preemptive commit comments blog post at https://arialdomartini.wordpress.com/2012/09/03/pre-emptive-comm it-comments/ by Arialdo Martini,

-

The Gitflow workflow: http://nvie.com/posts/a-successful-git-branching-model.

Exceptional Excerpts

Table of Contents

- 01: Getting Started with Git

- 02: Git Fundamentals - Working Locally

- 03: Git Fundamentals - Working Remotely

- 04: Git Fundamentals - Niche Concepts, Configurations, and Commands

- 05: Obtaining the Most - Good Commits and Workflows

- 06: Migrating to Git

- 07: Git Resources

- Pages numbers from the pdf.

· 01: Getting Started with Git

· 02: Git Fundamentals - Working Locally

page 67:

- I prefer not to set up a global username and password in Git, as I usually work on different repositories using different usernames and emails; if I don’t pay attention, I end up doing a job commit with my hobby profile or vice versa, and this is annoying. So, I prefer setting up usernames and emails per repository; in Git, you can set up your config variables at three levels: repository (with the –local option, the default one), user (with the –global option), and system-wide (with the –system option). Later we will learn something more about configuration, but this is what you need for now to go on with.

page 75:

- Git uses four different types of objects, and commit is one of these. Then there are tree, blob, and annotated tag.

page 98:

[23] ~/grocery (master)

$ git checkout -

Switched to branch 'berries'

- New trick: using the dash (-), you actually are saying to Git: “Move me to the branch I was before switching”

page 100:

- In Git, you often have the need to point to a preceding commit, like in this case, the one before; for this scope, we can use HEAD reference, followed by one of two different special characters, the tilde~ and the caret^. A caret basically means a back step, while two carets means two steps back, and so on. As you probably don’t want to type dozens of carets, when you need to step back a lot, you can use tilde: similarly, ~1 means a back step, while ~25 means 25 steps back

page 116:

- Unstage is a word to say remove a change from the staging area

page 120:

The working tree (or working directory)

The staging area (or index, or cache)

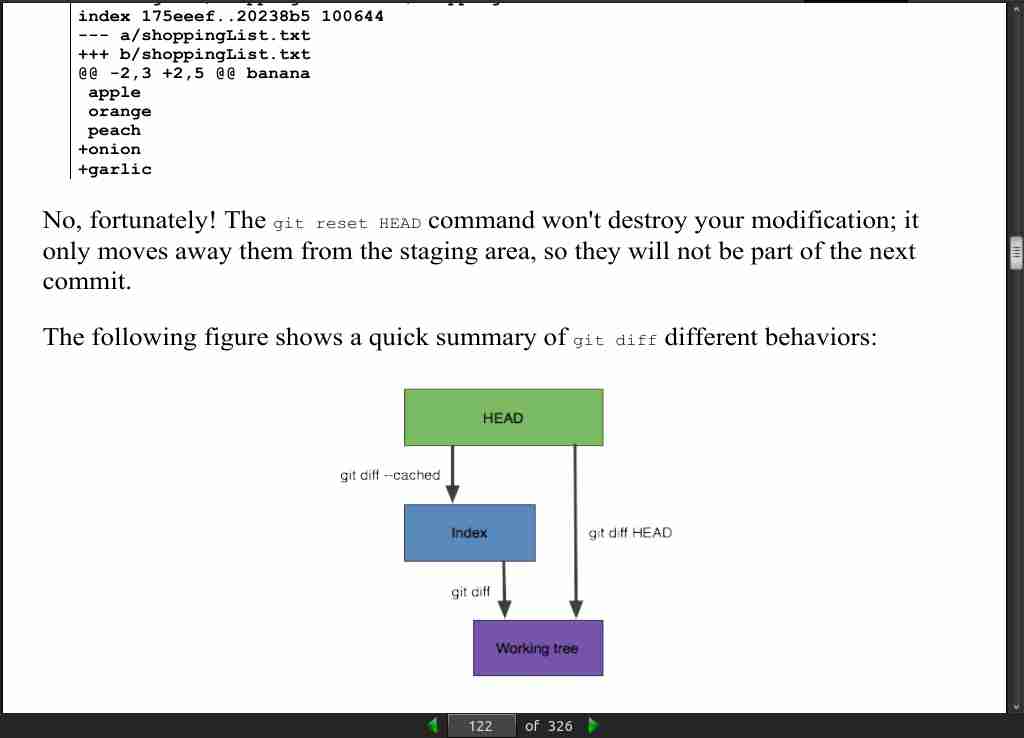

The HEAD commit (or the last commit or tip commit on the current branch)

- When we modify a file, we are doing it at working tree level; when we do a git add, we are actually copying the changes from the working tree to the staging area. At the end, when we do a git commit, we finally move the changes from the staging area to a brand new commit, referenced by HEAD

page 122:

page 124:

page 126:

· 03: Git Fundamentals - Working Remotely

page 166:

- git pull is a super command; in fact, it is basically the sum of two other Git commands, git fetch and git merge.

page 168:

- Note that you can do a git fetch in whatever branch you are in, as it simply downloads remote objects; it won’t merge them. Instead, while doing a git pull, you have to be sure to be in the right local target branch.

· 04: Git Fundamentals - Niche Concepts, Configurations, and Commands

page 207:

- To get a list of all the configurations currently in use, you can run the git config –list command

page 218:

- The classic example is the git unstage alias:

[1] ~/grocery (master)

$ git config --global alias.unstage 'reset HEAD --'

- With this alias, you can remove a file from the index in a more meaningful

way, compared to the equivalent git reset HEAD –

syntax:

[2] ~/grocery (master)

$ git unstage myFile.txt

- Now behaves the same as:

[3] ~/grocery (master)

$ git reset HEAD -- myFile.txt

page 234:

-

Bare repositories are repositories that do not contain working copy files, but only the .git folder. A bare repository is essentially for sharing: if you use Git in a centralized way, pushing and pulling to a common remote (a local server, a GitHub repository, and so on), you will agree that the remote has no interest in checking out files you work on; the scope of that remote is only to be a central point of contact for the team, so having working copy files in it is only a waste of space as no one will edit them directly on the remote.

-

using a .git extension; this is not mandatory, but is a common way to identify bare repositories.

page 235:

- You can easily convert a regular repository to a bare one using the git clone command with the same –bare option:

$ git clone --bare my_project my_project.git

- In this manner, you have a 1:1 copy of your repository in another folder, but in a bare version, ready to be pushed.

· 05: Obtaining the Most - Good Commits and Workflows

page 243:

- only make one change per commit.

page 245:

- Break a task down into constituent parts.

page 246:

- Write a single sentence describing each part; these are commit messages.

page 261:

page 268:

- gitflow commands Vincent made to customize his Git experience; check these out on his GitHub account at https://github.com/nvie/gitflow.

· 06: Migrating to Git

· 07: Git Resources

page 317:

- Learn Git Branching (https://learngitbranching.js.org/) is a tremendously helpful web app that offers you some exercises

page 320:

-

This group is frequented by Git pro users; if you need some help in getting out of difficult situations, the best place to ask for it is at; https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/git-users.

-

The internet has plenty of good cheat sheets about Git; here are my preferred ones:

Git pretty: http://justinhileman.info/article/git-pretty/

Hylke Bons Git cheat sheet: https://github.com/hbons/git-cheat-sheet