Home · Book Reports · 2018 · The Act of Creation

- Author :: Arthur Koestler

- Publication Year :: 1964

- Read Date :: 2018-07-12

- Source :: Koestler_Arthur_- Act_of_Creation_(Hutchinson_1964).pdf

designates my notes. / designates important.

Thoughts

This is a long book that covers a lot of ground. The first part is pretty easy going, while the second, as warned, is more technical.

Having read The Ghost in the Machine, I could see the roots of those ideas; would it be better to read Koestler’s works in order? I do not know, but they certainly support and elucidate one another in any order. The reader’s preference on how certain points are made, which analogies are used, how technical or lay the arguments are made will ultimately be the subjective factor in one’s judging a ‘correct’ order to read them. That said, I plan to read The Lotus and the Robot (1966) and Janus (1979) in that order. This book was 1964 and Ghost in the Machine was 1989.

Agree or disagree, waterboy for the oligarchy or not, this book, like his other works is thought provoking and well worth the time and effort required to sufficiently absorb its position.

While we should be wary of guilt-by-association, Koestler was friends with Schrodinger, von Neumann, and supposedly met Tim Leary and tried psychedelics.

The symbology in the triptych, the 3 panel screen, is interesting. The leftmost panel depicts a jester, in the center panel we see a sage, and the rightmost panel displays a poet. All three interplay with one another in the creative process.

I think one of the most important points the book makes is that of the concept of bisociative instead of associative; the connecting two unrelated frames, or matrices, of reference. I believe Einstein said something similar. While not limited to, the ability to think creatively often includes linking two seemingly unrelated data.

The foreword wastes no time in reinforcing my initial suspicion that Koestler was at best influenced by some of histories more unsavory personalities. Galton is mentioned in regard to breeding intellectuals, while Watson in regard to rearing geniuses.

Book One: The Art Of Discovery and the Discoveries of Art

Part 1: The Jester

Chapter one sets the stage to talk about laughter with a few, funny, examples (one by friend of Koestler: John Von Neumann).

Chapter two continues to explore laughter. It argues that laughter can be seen as aggressive. Support for this position is presented that many philosophers agree. It can be seen as a way to humiliate, and thus correct, fellow man. This is obviously seen more in children with their chiding, teasing, and practical jokes. As we mature laughter/humor tends to move from toilet humor to witty remarks.

Koestler argues that if there is a group of school children listening to violinist and a string breaks they will all laugh. The children, he claims, were pent up and the excess energy would be seen in fidgeting. When the string snaps, so to does the emotion barely held in check.

Instead of an outlet for pent up emotion, could it be an outlet for a redundant emotion? Is laughter is the intellects way of puffing away emotion?

Aldous Huxley, another fine example of the seedy types Koestler is influenced by, claims that man’s mind hasn’t caught up with his environment. How emotions still rule. We channel them inward (creatively?) or outward and ‘start hitting people’.

My personal take is that laughter is some kind of blow-off valve and it certainly helps us deal with things much more serious than would rationally elicit laughter. Some people laugh as a way to grieve and people to this day will laugh at things like an out of control government, calling them stupid and brushing them off. This is not far off from the allusion made to by the triptych’s jester. The jester was the only one able to make fun of the king in his court. Everyone could laugh and the potential aggression they might have held for the king dissipated. In modern times you see something eerily similar with the modern day jesters like Jon Steward or Steven Colbert poking fun at politicians that are, by many objective metrics, are little more than criminals, gangsters, and thugs.

Chapter three moves into what we might call the trigger of laughter, the varieties of humor: caricature, satire (verbal caricature), clowns, tickling (a response to mock-attack, does not always include laugh, always includes wriggling to get away), explicit versus implicit, leaving out enough, the economy of the joke, to force the listener to solve the riddle to get the joke.

Additionally humor can be extra explicit, pile it on, slapstick, like the clown. It can include impersonation, a jack-in-the-box, or man on strings/puppet.

The creativity, the originality, lies seeing something another way. An example joke is given as the Marquis, upon finding his wife with a Bishop, goes to the window and starts blessing passer-byers. Why, asks the Bishop. You’re doing my duties, I’ll do yours. It is logical, but absurd.

Comic discovery is paradox stated – scientific discovery is paradox resolved.

Finally there is a little discussion on Alice in Wonderland, Aldous Huxley’s The Island vs. Brave New World, and two mentions of Caliban vs. Ariel (Shakespeare’s The Tempest).

Chapter four posits that humor and discovery have some common ground. A joke that needs to be gotten is not different, except by degree, from discovering a solution to a scientific problem.

Moving from toilet humor to more intellectual humor we see the move toward discover. To get the joke you must see it, the more it is hidden, the more riddle like it is, the more difficult to discover. Once discovered the audience gets the release of a Eureka moment.

Animal Farm and 1984 taught a whole generation more about the nature of totalitarianism than academic science did.

This is telling when seen from my perspective. The move away from academic understanding (back?) to a system of social control where stories, no told by a centralized media, are shaping culture. Story books teaching whole generations. I say back to this system because historically people we controlled by stories that we find in religious text or oral traditions. The “campfire story” likely dates back into prehistory. That isn’t to say any of these things are bad, I don’t think that at all, but their existence to the exclusion of a more Aristotelian, a more grounded, way of passing on information to future generations seems to me to be more corruptible; it is hard to hijack 2 + 2 = 4, it is easy to insert or omit one or two critical sentences in a story to twist the meaning.

Part 2: The Sage

Chapter five visits the thought that creativity is when you make a logical leap from a known to an unknown that in hindsight seems obvious. The example Koestler uses is one in which chimpanzees use sticks to rake in bananas. At first the stick is a mere toy, used to push around banana peels and scratch in the dirt. Next bananas are introduced and placed out of reach. At first the chimp laments, then balks, then, upon seeing the stick in a new light, rakes them in. Later when out of reach bananas are introduced and there is no stick present, the chimp breaks a branch off a tree or bush for the same effect.

Koestler concludes that blocked situations induce stress and in that stress you are able to see in new light, as with Archimedes and his tub.

He backs this up with several examples of scientists, mostly mathematicians, experiencing a flash of insight to solve a novel problem. A few said specifically that they have, on many occasions, woken up to an answer. I have experienced this enough times to not question its validity. ‘Sleep on it’ comes from real world advice.

Chapter six tells three stories of scientific discovery coming out of colliding views.

First was Gutenberg, bring together engraving, casting coins, and a wine press to invent the printing press.

Second was Kepler bringing together astronomy and physics when he was at his wits end trying to fit orbits, of now greater accuracy thanks to Tycho, into circles. He went fishing in physics.

Third was Darwin, bringing together ideas from Malthus, Lamarck, E. Darwin, and Buffon, into his theory of evolution. In this story it is interesting to see several examples of Darwin lying, by his own admission.

Chapter seven posits that scientists are more like poets. They rely on intuition and then, after the fact, after they themselves are convinced, go back and prove it.

He mentions Galton several times, the coiner of eugenics, then an aside about how terrible Hitler was. Funny, Koestler, like Galton, has to deflect Galton’s deprave view onto an accepted monster. Cognitive dissonance or purposefully misdirecting?

He rehashes an old (even for then) idea that words induce limitations of conscious thinking. That language is as much a hindrance and helper. The idea goes something like: you can’t think about something you don’t have a word for. It seems reasonable at a glance, but if it were true, nothing would even have been invented in the first place.

The meaning of words, like Space and Time, I would agree do limit new ways of thinking about them. Lazy Einstein, waiting until after childhood to think about common sense stuff like space and time.

An interesting question Koestler poses: are thoughts like island rising up out of an unconscious ocean, or like icebergs?

He puts for that many mathematicians seem to mostly think visually, with some exceptions (Weiner, Polya).

While it all ‘feels’ well and good, I can’t help but shake there is an attack on language, communication, in here somewhere.

Chapter eight explores things like dreaming and the naive, open thinking of a child. When a child is watching a thriller on television their heart racing (not only children as the case may be) even though there is no actual reason for it to race. There isn’t really a killer lurking about or what have you. It is their naivete that allows children to more easily suspend disbelief.

Koestler submits that the most fertile ground is between waking and dreaming, the first hour or so after you’ve waken up.

“The half-hour between waking and rising has all my life proved propitious to any task which was exercising my invention. . . . It was always when I first opened my eyes that the desired ideas thronged upon me.” (Beveridge, W. I. B., 1950, pp. 73-4)

For this reason it is suggested to keep a pen and pad by your bed.

Sometimes ideas can lay dormant for years, decades, before colliding with another matrix to allow them to be truly seen. Franklin wanting to get at lightning, remembering using a kite as a child (to pull him in the water, he was an expert swimmer). Gutenberg’s seeing the wine press, plus the seals he already knew, to invent the printing press.

Chapter nine details false inspirations and great ideas left on the vine.

Kepler knew for three years ellipses were the movement of the planets, but could not bring himself to admit it. He also worked out, then discarded essentially the theory of gravity. He knew bodies attracted, he knew it was proportional to mass. Still, he couldn’t see the value.

Freud brought the world cocaine, calling it a ‘magic drug’, said it had no side effects. After the scourge had been set upon humanity, other doctors realized, though Freud knew and dismissed, that cocaine could be used to numb the external body. It was later used as an anesthetic. Used the first time in eye surgery on Freud’s own father. The author notes the similarity to A. Huxley and mescaline.

Watson, the behaviorist, trained a child at the age of five months, six full months early, to associate the word ‘da’ with bottle.

Chapter ten contents that facts alone are not enough to bring about new theories. A creative/original thinker needs to synthesize facts into something greater than their parts.

“There is usually, at the heart of any new development, a moment of intuition, that is built, polished, and eventually proved. Though it did start as a vague notion.” T.H. Huxley.

Plutarch realized that the moon stayed up because of its revolution about the earth. The Royal Societies Glanvill buried evidence on witchcraft that was later supported by hypnosis.

Scientists shouldn’t worry if the experiment disproves their theory or formula, it may be that the experiment will itself be disproved later!

Pasteur stressed the environment for micro organisms, Koestler notes that we still have not learned the lesson: food packaged in such sterile way deprives us of the ‘bugs and muck’ that make a healthy environment.

Physics, and now much of science, has been subsumed by mathematics. Physicists in particular, theoretical physicists, ask us to reject matter for symbols. This flies in the face of age-old advice: the map is not the territory, or as I like to rephrase it, the math is not the territory.

The history of science is zig-zag, not a continuous progress forward. What we think we know today becomes laughable in a generation and might well be back in vogue in a century.

Chapter eleven discusses the three kinds of scientists: the benevolent magician, the mad professor, and, in the middle, the dull modern lab-coat donning scientist.

There is a lot of overlap between science and art, a common theme to this point. The scientist needs creativity and originality to make discoveries, he needs some kind of drive, financial, game, or power, to keep him going year after year.

Koestler mentions, and alludes to more later, that students learn when presented with problems to solve, not told to memorize theorems. This I can agree with. As does Polya.

Ironically scientists are often religious, although sometimes of a different type, an unorthodox type. Einstein said he had cosmic religion, once calling upon pantheism to describe it. There are many other examples, Pasteur, Kepler, Bertrand Russell. It is interesting to me because in the modern era a great many (scientifically illiterate) people chant things like: “trust the science”. Not only do they not know anything about the scientific method, their blind trust is much akin to a religion, something many of them denounce heartily as atheists.

Part 3: The Artist

Chapter twelve takes a brief look at weeping, as distinct from crying, in much the same fashion as laughter has been previously discussed. There was very little literature to draw on so the topic is scant.

Weeping shown to be, possibly, another, opposite, outlet for overheated emotional drives, such as with laughter.

Often laughter and weeping will coincide, as with a mother discovering that her missing child has returned home safely.

Television, and how it can introduce shared emotion, is mentioned several times. I think this is one of the more important points that is taken for granted, that TV can lull us into passivity or work us into a faux rage; both cases to the benefit of an oligarchy. Example: the cheers and jeers surrounding the artificial combat of a football game can provide an outlet that might otherwise be directed to more worthy, like, say, the Hamptons, targets.

One example given are the real anxiety and real jumps one might experience watching a thriller.

Chapter thirteen is the foundation of what was covered more extensively in The Ghost in the Machine. The thought revolves around sub units, later called holons, that make up whole units; but what is a whole unit? If a cell is a part of an organ, is the organ the whole since it is part of the body? The body though is part of the family, which goes on up and up past the tribe to the global population. You could then extend it further, the population on earth is part of earth, which is part of the solar system, etc, up to infinity. This concept seems to work downward to the sub-atomic also. I am reminded of: “As above, so below.”

Chapter 14 contains a lot of, in my opinion, psycho babble. Of course there are lots of Freud references; this does nothing to improve my take on the chapter. One slightly interesting take is that babies, up until 2-3 years old, don’t see themselves as separate from the world around them.

Contrary to the last, chapter 15 was one of the most enlightening to me. It focuses on how fantasy and reality can easily overlap in a person’s mind. The example given is that a TV series elicited letters of sympathy and ire, directed at the characters (not actors). This shows, and has been seen many times before, that the TV/movie/book creates a fantasy that, for some people, bleeds into, becomes, their reality.

I have read before that villains on these various TV programs can often elicit similarly negative responses; some fans can’t distinguish between the story and the real.

This, in children and primitives (his words), can lead to a trance, addiction, and estrangement from reality. I wonder if he sees the masses as the primitives?

Through things like TV:

Liberated from his frustrations and anxieties, man can turn into a rather nice and dreamy creature;

The word “tragedy” comes from the Greek words “goat” and “song” and may have originated in Dionysian ceremonial rites. These rituals, from my understand, often included wine and psychedelic mushroom. These drugs combined with a fever pitch of celebration and pleasures of the flesh could have produced a similar disassociation from reality.

Chapter sixteen continues on the theme of manipulating people, this time with music instead of television. Koestler notes that in the modern music, rock-n-roll being very prominent at the time, people are more susceptible to the period of tones to noise. That is to say, the beat can lead us into trance-like states.

I think there is even more to this. How many of you can remember jingles and songs from childhood that you may not have heard in years? It might be hard to recall now, but if one of those songs began playing on the radio, you would instantly recall the words and likely be able to sing right along. Music, it seems, has a way of worming its way into our deepest memory. Song, as they say, can get “stuck in our heads.” This may be more literal than we imagine.

Chapter seventeen blends art an science a little more. Science shows its irrationality, valuing beauty over accuracy in mathematics. A beautiful solution is more salient than one verified by experiment. The artists inject an opposite amount of rationality through proportions, golden ratio, laws of perspective, etc.

Chapter eighteen continues to explore the seemingly juxtaposed science and art. Artists since antiquity said the best art captured nature perfectly, but that is impossible. Plato said that art is “man-made dreams for those who are awake.”

Later art was required to become more extreme, risqué, in-your-face, perverse, or shocking, to reach the same level of emotional charge. We became accustom to what was once inspiring. It became normal and we crave novel.

Recalling the way television can inject fantasy into your reality, one can see similar manipulation through other arts.

The witch-doctor hypnotizes his audience with the monotonous rhythm of his drum; the poet merely provides the audience with the means to hypnotize itself.

This reminded of a picture I saw from burning man. It was a sign that said something like: “self server brain washing: you wash your own brain.”

The escapist character of illusion facilitates the unfolding of the participatory emotions and inhibits the self-asserting emotions, except those of a vicarious character; it draws on untapped resources of emotion and leads them to catharsis.

This is the best synopsis of modern media in my opinion. You can see these kind of vicarious emotions play out in everything from super hero movies to sportsball games to politics. The viewer gets caught up in the spectacle of “their” hero/team/candidate and suffers all the highs and lows of victory and defeat from the comfort of their couch. The catharsis releases them from any real motivation to actually participate in the actual modern day battles in, for example, civil rights, economic injustice, or political corruption.

Chapter nineteen continues this theme of the fantasy becoming reality. First it is interesting to see how there are really only limited number of plots (Goethe’s 36) that the essence of the same few stories is re-skinned and retold over and over (Campbell’s hero’s journey).

Koestler claims, and I agree, that characters can be as or more real than real people, that the phantom can be more interesting than a real bore.

Interestingly, and I again agree, describing the character too much can force a concrete vision onto the reader. By giving a few hints and letting them fill in the blanks the picture will be more vivid in their mind. (Heinlein’s Starship Troopers offers no description of the protagonist until the very end).

Chapter twenty discusses recurring symbolism that we find in classic and modern stories. We see death and rebirth portrayed constantly. The protagonist must go through some ordeal, change, come out anew a la Joseph, Jesus, Jonah, Buddha, Mahomet, Orpheus, and Odysseus.

There is no direct mention of shamansim here, but it lurks right below the surface in this discussion.

Man lives in the trivial plane, but every once and a while slips to the tragic, sees the infinite, and comes back. Usually right back to his old habits.

Chapter twenty-one is another one that I found interesting. It tries to demonstrate that there is always a second matrix behind everything. By this he means that there is no way you can not be influenced by whatever is in your environment; if you want to make something original, shut yourself off from everything (even though you still were exposed up to the point you were shut off).

I remember reading about a musician that said something like this once. To make original music he stop listening to music completely.

This agrees with my view that everything that is made is tinted by environment. If the oligarchy has influenced modern art, and they have, all subsequent artists, whether card or water carrying members of the oligarchy or not, will produce works that are influenced, in the same vein, as oligarchical art. Eventually, through time, the oligarchy will have compounding returns on their influence.

Chapter twenty-two sort of builds on twenty-one in a manner. It explores the experience we have when looking at a work of art. It concludes that this experience is a series of instantaneous bisociations that can hardly be verbalized.

Inferences abound, we can not get away from them. We will literally be exposed to billboards and likely the radio on the way home from the hospital the day we are born. Our tastes and distastes, built from birth, play like consonances and dissonances. Everything we will ever think or do will be colored by these influences.

In Bernay’s Propaganda, he literally starts off the seminal work by proclaiming:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.

Chapter twenty-three circles back to the intertwining and similar nature of art and science. Art progresses in much the same way as science, with the pupils standing on the shoulders of the masters, but there is less literature describing the discoveries. This is not surprising since the words to describe a new technique could never rival the exposition of the new technique.

Chapter twenty-four rounds out book 1 by providing many examples of forgeries being accepted as masterpieces then later revealed to be forgeries, which no longer have the same appeal. Why? They are the same works that fooled the experts earlier. The conclusion is that snobbery, framing the work not by its own merit, but by the frame of reference that it is ‘real’, in knowing that it was painted by the hand of the ‘original’ is the actual appeal.

This appeal is not completely without merit. The genius lies not in the production of perfect pieces, but in blazing a new trail to open up new frontiers. From there, pupils can easily have greater technical mastery than the original. So the appeal of originals over forgeries could be seen as paying some kind of homage to the frontiersman of art.

Book Two: Habit and Originality

Chapter 1 starts off book 2 with a discussion on how dividing cells ‘decide’ what to do. Their ‘decisions’, of course, are base on environmental pressures known as epigenetics. One such pressure would be from surrounding cells and how they influence transplanted tissues. I think this was better explained in The Ghost and the Machine.

Chapter 2 show that in developing embryos, muscles reflexes can be stimulated before neuro-muscular integration. This lead the behaviorists to conclude the whole of reflexivity is built from the ground up. (S-R theory)

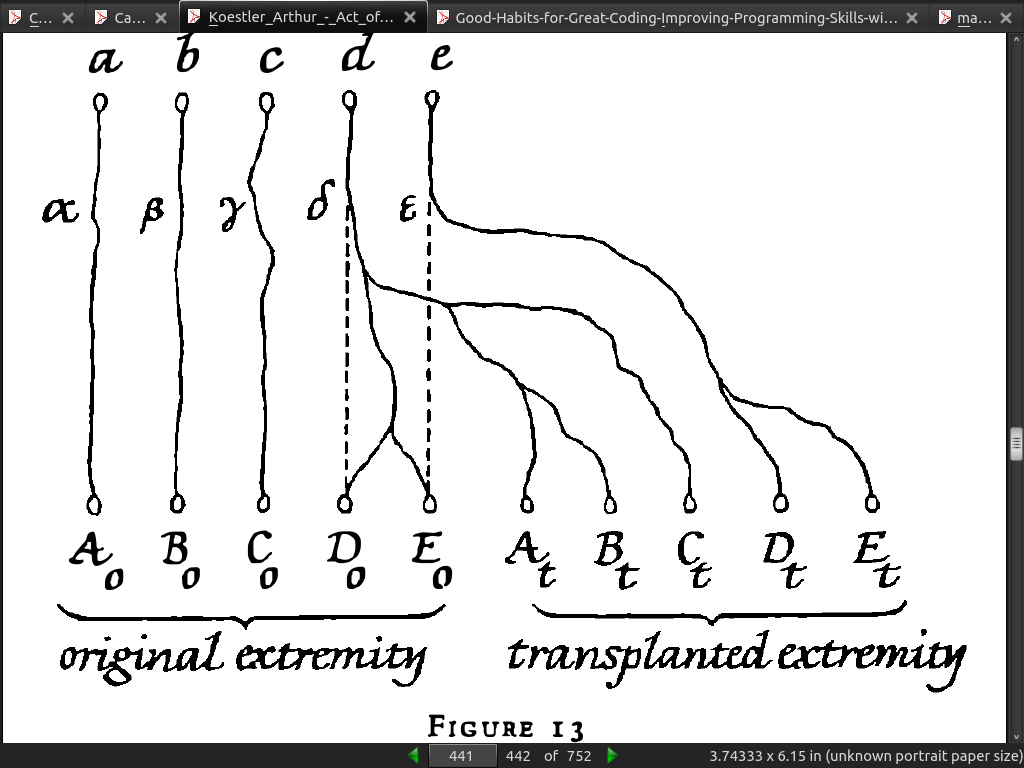

Weiss transplanted limbs of salamanders onto other salamanders. If an extra limb is transplanted next to another limb, after a few weeks lagging, it will start to function normally. If the limb is transplanted backwards, it will eventually work, but in reverse. If the forelimbs are swapped, the creature will never recover. When its hind legs try to more forward, the forelimbs move back and vice versa.

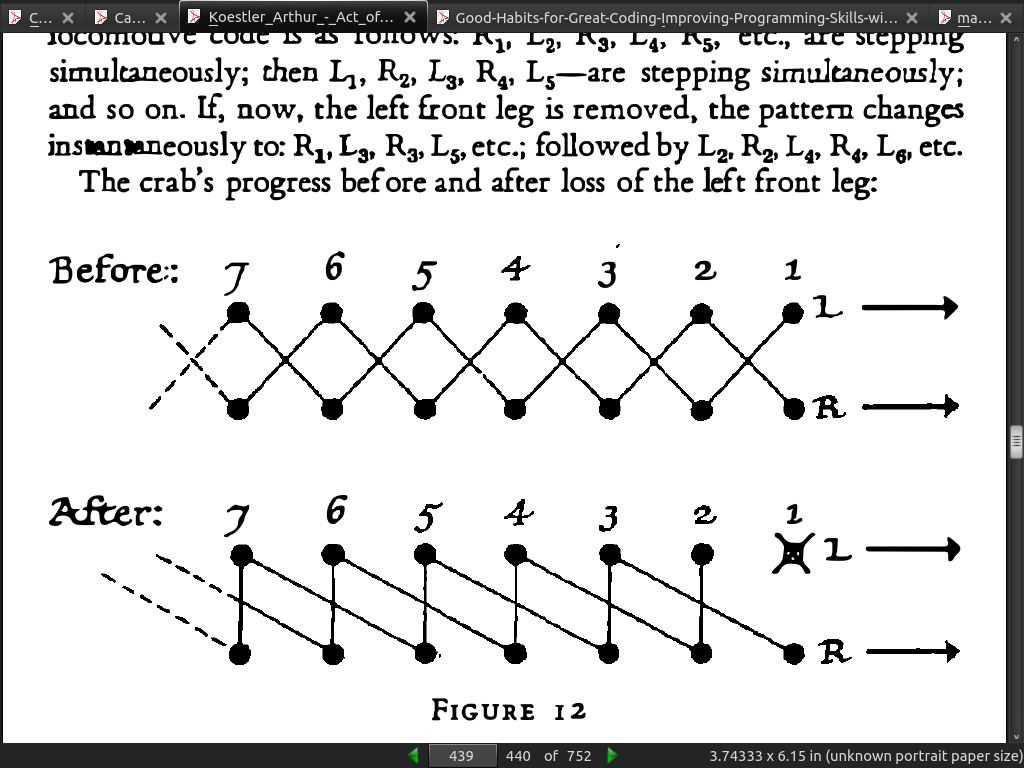

Removing a single, or multiple, leg from an insect or crab results in the reordering of leg movement in such a way that the first two legs, whatever they may be, act as a sort of metronome for the other legs. Odd patterns, where simpler could be reasoned, emerge. This seems to show that the legs are under their own control and not of the brain.

These experiments reminded me of Norber Weiner’s cybernetics research done with cat’s leg muscles. (Those experiments might not be detailed in that book)

Chapter 3 takes a somewhat more philosophical look at the differences and similarities in regeneration and asexual reproduction. These blend together on a gradient seen when cutting a flatworm in half in the lab equals regeneration, but in the wild it is asexual reproduction. I feel like this is merely a semantic difference and not particularly noteworthy.

Again we see more hair-splitting when Koestler talks about physiological regeneration - fixing the wear and tear is another level - in humans and how we ‘regenerate’ muscle, skin, and bone. And also that in higher level organism, regeneration is present in the embryonic stages. Twins may even be viewed as a kind of regeneration.

Chapter 4 revisits the comparison between death rebirth motif and the regression of cells before regeneration. The underlying theme in art is that one must go to the shadow side (death) and when you come out you are renewed (rebirth).

Experimentally Koestler justifies this view by offering up the observation that frogs can be stimulated to regrow legs they normally wouldn’t, a ham-fisted analogy to the shamanistic death-rebirth pattern.

Chapter 5 discusses triggers and feedback. The higher order components (brain) sends general signals to the lower order components (limbs) in such the same way as a general commands his lower ranks. The commands are general and interpreted/implemented by the lower order component. Similarity, feedback flows up the hierarchy.

This is presented in a much easier to digest manner in The Ghost and the Machine, where it is described as communicating holons.

Chapter 6 looks at the two ends of behavior: one rigid, ritual like. A cat burying feces on the kitchen tiles or a squirrel burying nuts in a wire cage. The other adaptable; birds making repairs to nests damaged by humans or wasps doing the same. This shows sometimes large deviations from the natural building habit.

Chapter 7 deals with what might be called part of the nature-nurture question. Goslings will imprint on humans when the humans are the first/only other animal around at birth. Later they will only associate with humans, as if they were human. Later still they will be able to distinguish between individual humans.

Some birds come batteries included with a song, others (skylark) have to learn it. Still others are somewhere in the middle, with some innate ability that must be honed through practice and learning.

Chapter 8 mentions Kurt Lewin, a pioneer of applied psychology and what I would today call psyops.

It also talks about fixed versus variable interval reward systems:

the rat thus trained is less discouraged when the reward is withheld, than the rat trained by the consistent-reward method.

This is a very important concept to understand. We see these reward systems used all around us. Your paycheck is an example of a fixed-interval reward system. You get paid every other Friday. This produces a low amount of addiction. You know what day you will get paid and how much you will get paid. There is no excitement. On the other hand, gambling is a variable-interval reward system. Every time you pull that bandit’s arm, you might bust or win a million bucks. The excitement level is high and the addiction potential is high.

Now consider how social media is structured. Every time you post, you might get a flood of likes and comments or crickets. This gambling-like format unsurprisingly produces high levels of addiction.

We can see a further similarity between school structure and fixed-interval systems. The bell rings and you change classes ever hour or so. A better comparison would be to the Pavlovian experiments with bells, food, and salivating dogs. (Although this was actually a smaller part of the experiment than most people realize. The larger part was using circles/ellipses to stimulate the dogs, but I digress)

The chapter continues by examining the exploratory drive in most animals. Hungry rats will delay feeding to explore novel environment, cross an electric grid to get to a novel maze (w/o reward), and monkeys will look into a box of snakes, that terrify them. A great many animals exhibit this inquisitive behavior, humans obviously included.

Chapter 9 submits that play is vitally important. It can be for fun, it can be for learning, practice, or exploration. I think we have been seeing the applied psychology of play over the last decade or so with the rise in ‘gamification’ as a way to motivate people into doing things they don’t want to do. While this seems well and good at first glance, I fear how it can be misused. See: Nudge by Cass Sunstein.

Chapter 10 explores perception. It begins with audition and how how we hear a fifty instrument and fifty singer orchestral, not individual tones, but individual instruments and voices. This is contrasted against Gestalt, which focus mainly on visual perception.

How we perceive is linked to how we remember. People that remember long lists of things often do so by creating stories around the list (ex: major system). Placing some kind of order on the random elements helps.

Memory itself is one-way; we see or hear something and it is pulled apart and bits and pieces are stored. Later upon recall the bits can only partial reconstruct what we think we remembered and then our imaginations flesh it out. A day after a theater, you can remember the plot vividly, but the lines are gone in seconds. A few days, a month, or year later your memory will be more and more a vague outline of the play.

Compared to other animals, man made an extra step with his symbols used to enhance memory and learning.

Chapter 11 covers the memory adjacent topic of learning. At first we learn by rote and then consolidate; a typist first needs a mental map showing all the keys, but eventually they start moving from letters to words as discrete units. When taking dictation, they lag a few words behind, for context.

It is the same with learning a musical instrument; at first it is every little pluck of a string, or press of a key, but then it becomes chords and eventually whole pieces.

Riding a bike is a little different, but it is still figuring out all the components. In this case, in not falling down. This comes, of course, much faster than typing or instrument playing. Once you learn it though, all the movements become second nature. A similar experience is seen when learning to drive a car. You don’t worry about the pedals, car or bike, the handlebars or the steering wheel, you’re concentration is at a higher level of the traffic, obstacles, etc.

In chapter 12, Koestler looks at learning in animals. When studying this, national scientists came to the very conclusions they wanted to when observing animals. Americans saw them as frantic, Germans saw them as contemplative, etc.

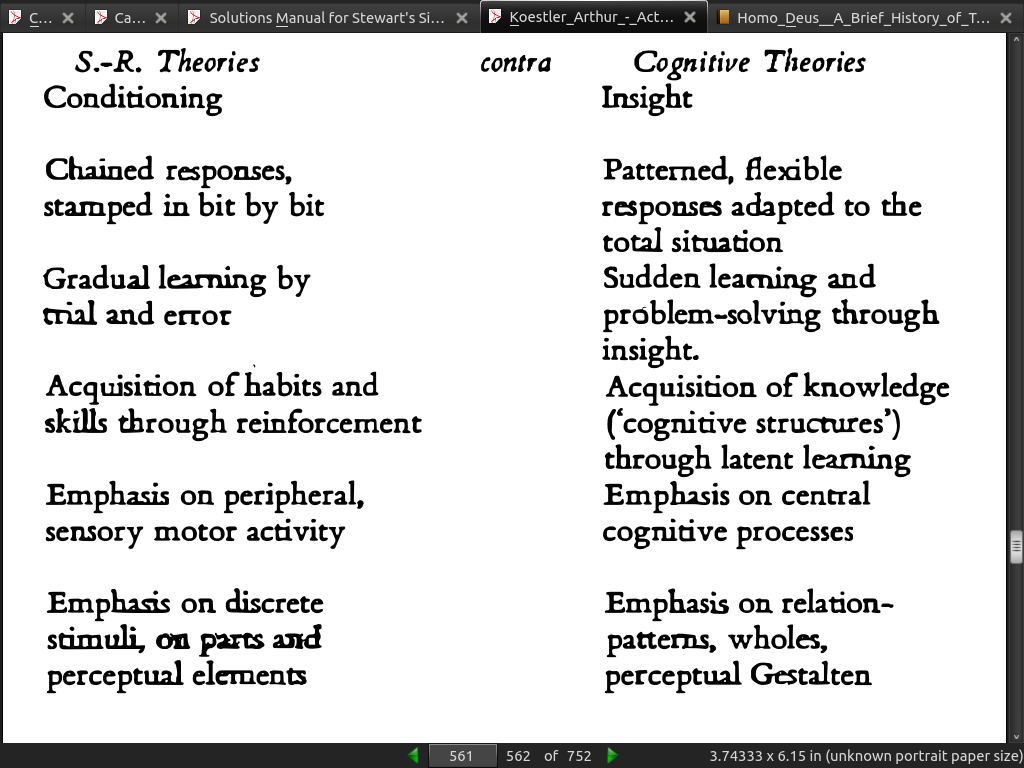

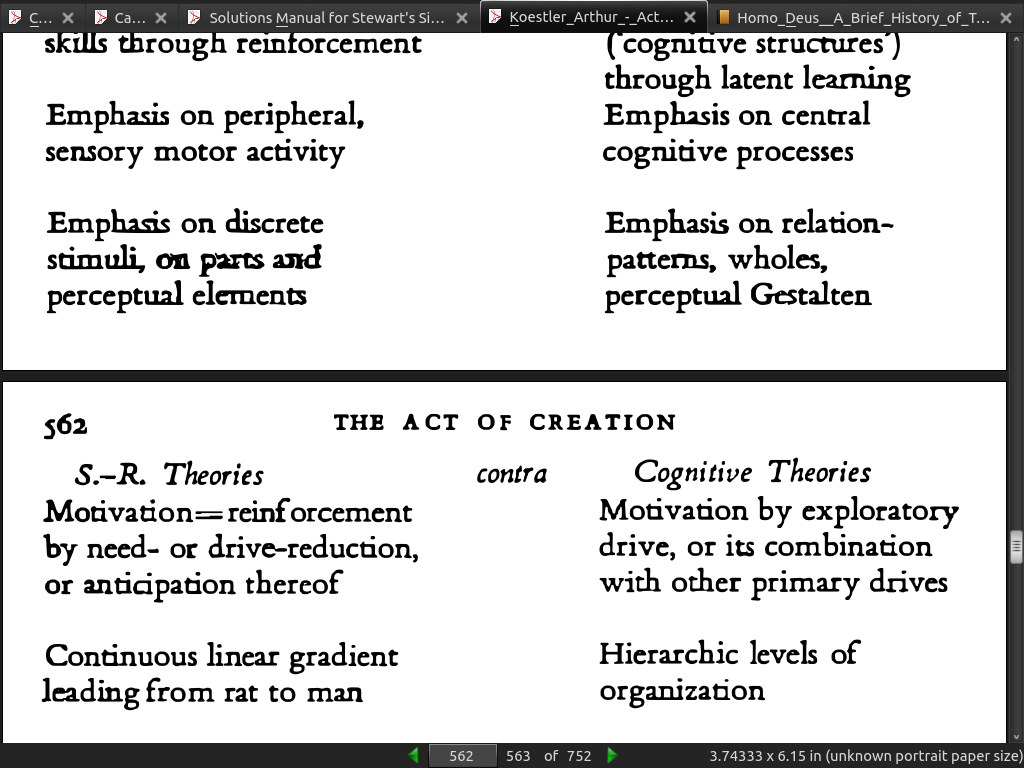

This leads to a discussion of Gestalt versus stimulus-response (S-R) theory, on insight versus drills.

Some of the more interesting example experiments include ones that demonstrate even insects have a large degree of learning and ‘insight’. Wasps can navigate around blocks placed in their path smoothly or fly and catch a large caterpillar and then drag it back to their nest on the ground, occasionally taking surveying flights but always remaining on course. Cats (like dogs with ovals) can be trained to get out of boxes by pulling strings or pushing levers, but they first spend 10 minutes thrashing around trying to squeeze out (naturally). Other cats shown a box with liver in it, suspended by a string, hanging just above the floor, the cat will eye it up carefully, looking up and down the string, then, at once, jump on top of the box and haul the liver out with teeth and paws pulling up the string.

Chapter 13 moves a little higher in the exploration of learning in animals (and humans). Even seeing all the parts that will combine into a solution is not always enough to actually get to the solution. Kohler’s chimps put 2-3 sticks together into a long rake to get bananas and stacked boxes to get bananas, but they were primed by being allowed to play with sticks and boxes. Without that playtime, it took longer, if ever, for the chimp to get the bananas.

Like the cats in the box, freaking out before learning how to pull the rope or spin the bolt to get out, the chimps don’t have boxes in their natural environment and will have to incorporate them into their world view. The same can be said about Pavlov’s oval selecting dogs. All of these things go against the animal’s grain as it were and can only take hold after their natural tendencies wane.

Chapter 14 looks at language and verbal learning versus visual learning. First it notes, and I completely agree, how amazing language is. We never really think about what we are going to say, but there it is.

When writing a lecture, book, or anything in between, we generally outline or sketch out our idea in the roughest form. We can then rearrange the order, decide whether will stay abstract or provide concrete examples, etc. Only much later do we set down ink to paper on formulate full turns of phrases, sentences, and ideas that take shape as the whole.

When we try to teach a human to traverse a maze, specifically a round maze:

the visualizers learned twice as fast, the verbalizers four times as fast as the motor learners.

While words are very important, one must remember, as discussed earlier in the book, to quote Woodworth, ‘often we have to get away from speech in order to think clearly’.

In an experiment where low voltage was applied to the cortex to create artificial aphasia, patients ranged from not being able to speak at all while the voltage was applied, to speaking everything except what they saw.

We may safely conclude, then, with Humphrey: ‘Clinical, experimental, and factorial results agree that language cannot be equated with thinking. Language is ordinarily of great assistance in thinking. It may also be a hindrance.’

This runs counter to what I’ve always thought, that one needs words to describe things before they can think them. The evidence presented is reasonable.

Chapter 15 discusses conditioning and curiosity. One interesting point, that supports the view that humans learn in dichotomies, is that children will confuse up-down or left-right, but only in opposites. They don’t move left when told to go down.

While Pavlov and Skinner at least limited their experiments to animals, Watson has little to no scruples and goes right after children. These kinds of experiments were the inspiration for Huxley’s Brave New World (specifically the first scene with the babies and flowers on the electrified floor).

Watson’s famous experiment intended to establish a ‘conditioned fear reflex’ in an infant eleven months of age, by striking an iron bar with a hammer each time the child touched its pet animal, a white rat. After this was repeated several times within the span of a week, little Albert responded with fear, crying, etc., whenever the rat was shown to him. But he also showed fright-reactions in varying degrees to rabbits, fur coats, cotton wool, and human hair-none of which had frightened him before.

In more reasonable conditions, children find out everything has a name and then they constantly ask ‘what is it called?’ Then they find out everything has a because and constantly ask ‘why?’ Both the name and the because may be wrong when first learned, but later when they are fixed, the language is not lost. Why doesn’t the sun fall down? Because it is yellow. When this is fixed the child still knows what yellow is.

Another Alice in Wonderland reference is made here…

Chapter 16 continues looking at language and things like word association of opposites or synonyms and how they produce totally different results.

Chapter 17 continues on 16 and goes into more detail on associations. Free association is never truly free, it is at least guided by unconscious. This again brings me back to the point that we are all influenced by our environment from the moment we are born. We need to be very careful with the power over our environment might have over us as we mature. (advertising prescription drugs in the USA leads to massive [over?] prescription of drugs)

There are several categories that associations fall into:

Wells4 once made a catalogue of eighteen types of association adapted from Jung, such as: ’ egocentric predicate’ (example: lonesome-never) ; ’evaluation’ (rose-beautiful) ; ‘matter of fact predicate’ (spinach-green); ‘subject-verb’ (dog-bite) , and so forth, through ‘object-verb’, ‘cause-effect’, ‘co-ordination’, ‘subordination’, ‘supraordination’, ‘contrast’, ‘coexistence’, ‘assonance’, etc. Woodworth (1939) suggested four classes: definition including synonyms and supraordinates; completion and predication ; co ordinates and contrasts ; valuations and personal associations.

Chapter 18 mentions Polya (See: How to Solve it) and the tree-bridge problem. To solve a problem, assume the problem is solved. This is what is taught as reverse planning in the military. Assume you are at the position you want to be at and then work your way back to where you are.

Appendix 1 gives a brief history of electricity and magnetism finding their way into one eventually all energy (kinetic, electric, etc) was seen to be exchangeable.

Appendix 2 is a collection of short passages recounting some of the great minds; how they were sometimes saints, sometimes monsters, sometimes both.

Great mind would likely be great no matter what path they take. One-idea men, like Copernicus or Darwin are exceptions to the likes of Edison, Galileo, Kepler, Pasteur, etc. Great general intellect fixed on a specific instead of a general. They never stop asking why and expecting answers can be found.

Further Reading

- Erewhon

- Some of Koestler’s other works of interest: Lotus and the Robot, Darkness at Noon

- Cannon’s “Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear, and Rage”

- Miller, Galanter, and Pribrarn’s remarkable essay on ‘Plans and the Structure of Behaviour’ (1960)

- Koffka’s Principles of Gestalt Psychology

- Bryan and Harter’s Studies on the Telegraphic Language. The Acquisition of a Hierarchy of Habits.2

- Kohler’s Mentality of Apes in 1925

Exceptional Excerpts

'Give me', said Professor Watson, the apostle of behaviourism, 'half a dozen healthy infants and my own world to bring them up in, and I will guarantee to tum each one of then1 into any kind of man you please-artist, scientist, captain of industry, soldier, sailor, beggar-man, or thief.'

Comic discovery is paradox stated – scientific discovery is paradox resolved.

The remark that he had arrived at his ideas independently from his predecessors should not perhaps be taken at face value, for Darwin's own notebooks are conclusive proof that he had certainly read Lamarck, the greatest among his precursors, and a number of other works on evolution, before he arrived at formulating his own theory. Even so, the intended apology never found its way into the book which it was meant to preface.

The translation is by Heath, who remarks: ‘This is practically Newton’s first Law of Motion.’

the pleasurable experience is derived not from anticipating, but from imagining the reward

Liberated from his frustrations and anxieties, man can turn into a rather nice and dreamy creature;

‘the structure of the input does not produce the structure of the output, but merely modifies it.’

The core of the controversy could be summed up in shorthand as ‘drill’ versus ‘insight’.

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- 1_01: The Logic of Laughter

- 1_02: Laughter and Emotion

- 1_03: Varieties of Humor

- 1_04: From Humor to Discovery

- 1_05: Moments of Truth

- 1_06: Three Illustrations

- 1_07: Thinking Aside

- 1_08: Underground Games

- 1_09: The Spark and the Flame

- 1_10: The Evolution of Ideas

- 1_11: Science and Emotion

- 1_12: The Logic of the Moist Eye

- 1_13: Partness and Wholeness

- 1_14: On Islands and Waterways

- 1_15: Illusion

- 1_16: Rhythm and Rhyme

- 1_17: Image

- 1_18: Infolding

- 1_19: Character and Plot

- 1_20: The Belly of the Whale

- 1_21: Motif and Medium

- 1_22: Image and Emotion

- 1_23: Art and Progress

- 1_24: Confusion and Sterility

- Book 2_Introduction

- 2_01: Prenatal Skills

- 2_02: The Ubiquitous Hierarchy

- 2_03: Dynamic Equilibrium and Regenerative Potential

- 2_04: Reculer Pour Mieux Sauter

- 2_05: Principles of Organization

- 2_06: Codes of Instinct Behaviour

- 2_07: Imprinting and Imitation

- 2_08: Motivation

- 2_09: Playing and Pretending

- 2_10: Perception and Memory

- 2_11: Motor Skills

- 2_12: The Pitfalls of Learning Theory

- 2_13: The Pitfalls of Gestalt

- 2_14: Learning to Speak

- 2_15: Learning to Think

- 2_16: Some Aspects of Thinking

- 2_17: Association

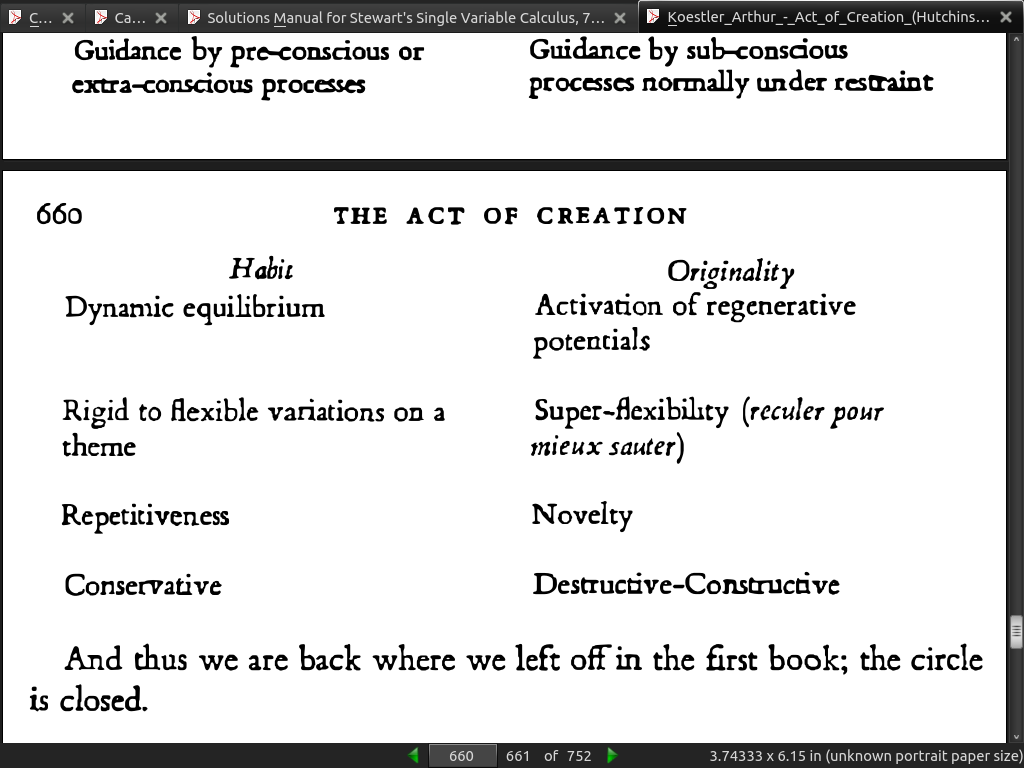

- 2_18: Habit and Originality

- Appendix 1: On Loadstones and Amber

- Appendix 2: Some Features of Genius

Book One: The Art Of Discovery and the Discoveries of Art

Part One: The Jester

Part Two: The Sage

Part Three: The Artist

Book Two: Habit and Originality

- Pages numbers from the actual book.

· Foreword

page 14:

- By collecting pedigrees, measuring abilities, and applying statistical techniques, Sir Francis Galton proved, or thought he could prove, that the most important element in genius was simply an exceptionally high degree of the all round mental capacity which every human being inherits-‘general intelligence’. And, reviving a proposal that originated with Plato, he contended that the surest way to manufacture geniuses would be to breed them, much as we breed prize puppies, Derby winners, and pedigree bulls.

-

‘Give me’, said Professor Watson, the apostle of behaviourism, ‘half a dozen healthy infants and my own world to bring them up in, and I will guarantee to tum each one of then1 into any kind of man you please-artist, scientist, captain of industry, soldier, sailor, beggar-man, or thief.’

-

Aut Caesar aut nul/us is not an axiom to which the modem historian would subscribe either in these or any other in stances.

Book One: The Art Of Discovery and the Discoveries of Art

Part One: The Jester

· 1_01: The Logic of Laughter

page 32:

-

Some of the stories that follow, including the first, I owe to my late friend John von Neumann, who had all the makings of a humorist: he was a mathematical genius and he came from Budapest.

-

Pascal’s motto: ‘Le ccrur a ses raisons que Ia raiso11 11e connaft point.’ Or, to put it in a more abstract way: The controls of a skilled act ivity generally function below the level of consciousness on which that activity takes place. The code is a hidden persuader.

page 48:

- In modem science it has become accepted usage to speak of the ‘mechanisms’ of digestion, perception, learning, and cognition, etc., and to lay increasing or exclusive stress on the automaton aspect of the homme-automate.

· 1_02: Laughter and Emotion

page 53:

- A number of philosophers agree: laughter is connected with contempt, derision, superiority, and similar, less civilized, actions and feelings. This is seen, most obviously, in the chiding of school children. Could laughter be a way to correct, through humiliation, our fellow man? What would the cry-bullies of today say to this?

page 55:

- emotion tends to beget bodily motion

page 56:

- In a word, laughter is aggression (or apprehension) robbed of its logical raison d’etre; the puffing away of emotion discarded by thought.

page 58:

- It is emotion deserted by thought which is discharged in laughter. For emotion, owing to its greater mass momentum, is unable to follow the sudden switch of ideas to a different type of logic or a new rule of the game; less nimble than thought, it tends to persist in a straight line. Ariel leads Caliban on by the nose: she jumps on a branch, he crashes into the tree.

page 59:

- The sudden bisociation of a mental event with two habitually incompatible matrices results in an abrupt transfer of the train of thought from one associative context to another. The emotive charge which the narrative carried cannot be so transferred owing to its greater inertia and persistence; discarded by reason, the tension finds its outlet in laughter.

page 62:

-

Discussing the problem of man’s inn ate aggressive tendencies, Aldous Huxley once said:

-

“On the physiological level I suppose the problem is linked with the fact that we carry around with us a glandular system which was admirably well adapted to life in the Paleolithic times but is not very well adapted to life now. Thus we tend to produce more adrenalin than is good for us, and we either suppress ourselves and turn destructive energies inwards or else we do not suppress ourselves and we start hitting people.“12

page 63:

-

Beneath the human level there is neither the possibility nor the need for laughter; it could arise only in a biologically secure species with redundant emotions and intellectual autonomy.* The sudden realization that one’s own excitement is ‘unreasonable’ heralds the emergence of self-criticism, of the ability to see one’s very own self from outside; and this bisociation of subjective experience with an objective frame of reference is perhaps the wittiest discovery of homo sapiens.

-

Thus laughter rings the bell of man’s departure from the rails of instinct; it signals his rebellion against the singlemindedness of his biological urges, his refusal to remain a creature of habit, governed by a single set of ‘rules of the game’. Animals are fanatics; but ‘0 I How the dear little children laugh I When the drums roll and the lovely Lady is sawn in half…‘13

· 1_03: Varieties of Humor

page 67:

- Lewis Carroll sent the following contribution to a philosophical symposium:

'Yet what mean all such gaieties to me

Whose life is full of indices and surds?

X^2 + 7X + 53

= 11/3'

page 72:

-

The humorist’s motives are aggressive, the artist’s participatory, the scientist’s exploratory.

-

A map bears the same relation to a landscape as a character-sketch to a face; every chart, diagram, or model, every schematic or symbolic representation of physical or mental processes, is an unemotional caricature of reality.

-

The satire is a verbal caricature

page 73:

- Writers of Utopias are motivated by revulsion against society as it is, or at least by a rejection of its values; and since revulsion and rejection are aggressive attitudes, it comes more naturally to them to paint a picture of society with a brush dipped in adrenalin than in syrup or aspirin. Hence the contrast between Huxley’s brilliant , bitter Brave New World and the goody goody bores on his Island.

page 78:

-

When the White Queen complains: ‘It’s a poor sort of memory which only works backwards,’ she is putting her finger on an aspect of reality-the irreversibility of time-which we normally take for granted; her apparently silly remark carries metaphysical intimations, and appeals to our secret yearning for the gift of prophecy-matters which would never occur to Alice, that little paragon of stubborn common sense.

-

More Alice in Wonderland.

· 1_04: From Humor to Discovery

page 89:

- Moving from toilet humor to more intellectual we see the move toward discover. To get the joke you must see it, the more it is hidden, the more riddle like it is, the more difficult to discover. Once discovered the audience gets the release of a Eureka moment.

page 90:

- Animal Farm and 1984 taught a whole generation more about the nature of totalitarianism than academic science did.

page 95:

- Comic discovery is paradox stated – scientific discovery is paradox resolved.

Part Two: The Sage

· 1_05: Moments of Truth

page 102:

- 1918 Kohler experimenting with chimpanzees. Give a caged animal a stick; they play with it. Later put bananas just out if their reach. After some lamenting, they will eventually see that the stick they previously only played with can be used to rake in the bananas. The second time bananas are placed out of reach the stick is employed more rapidly. The third, and subsequent, time, the stick is employed immediately. There is no hit-and-miss evolution of the process of raking with the stick. The very first time the chimpanzee decides to use the stick to get the bananas, it does so just how you’d expect, placing the stick behind the bananas and raking them in. Subsequent use is more graceful, but from the beginning it is well reasoned what is to be done.

page 103:

- ‘It is remarkable’, wrote Laplace, ’that a science which began with considerations of play has risen to the most important objects of human knowledge.’

page 104:

- Later chimpanzee’s figure out that branches can be broken off a trees and used the same way. They never forget it.

page 105:

- Blocked situations increase stress. Under its pressure the chimpanzee reverts to erratic and repetitive, random attempts; in Archimede’s case [ in trying to figure out if the crown was pure gold] we can imagine his thoughts moving round in circles within the frame of his geometrical knowledge; and finding all approaches to the target blocked.

page 109:

- We may distinguish between the biological ripeness of a species to form a new adaptive habit or acquire a new skill, and the ripeness of a culture to make and to exploit a new discovery. Hero’s steam engine could obviously be exploited for industial purposes only at a stage when technological and social conditions made it both possible and desirable.

page 117:

- Several pages of examples where the solution to a problem comes as a flash of insight, often upon first awaking.

page 120:

- ‘It is obvious’, says Hadamard, ’that invention or discovery, be it in mathematics or anywhere else, takes place by combining ideas. … The Latin verb cogito for “to think” etymologically means “to shake together”. St. Augustine had already noticed that and also observed that intelligo means “to select among”.’

· 1_06: Three Illustrations

page 133:

-

Thus Darwin originated neither the idea nor the controversy about evolution, and in his early years was fully aware of this. When he decided to write a book on the subject, he jotted down several versions of an apologetic disclaimer of originality for the preface of the future work:

-

“State broadly [that there is] scarcely any novelty in my theory . . . The whole object of the book is its proof, its extension, its adaptation to classification and affini ties between species. Seeing what von Buch (Humboldt), G. H. Hilaire [sic] and Lamarck have written I pretend to no originality of idea (though I arrived at them quite independently and have read them since). The line of proof and reducing facts to law [is the] only merit, if merit there be, in following work. 12” -Darwin

-

The remark that he had arrived at his ideas independently from his predecessors should not perhaps be taken at face value, for Darwin’s own notebooks are conclusive proof that he had certainly read Lamarck, the greatest among his precursors, and a number of other works on evolution, before he arrived at formulating his own theory. Even so, the intended apology never found its way into the book which it was meant to preface.

-

Darwin… lying! I’m shocked.

page 134:

-

In his early notebooks, not intended for publication, Darwin paid grateful tribute to Lamarck as a source of inspiration, ’endowed with the prophetic spirit in science, the highest endowment of lofty genius’. Later on he called Lamarck’s work ‘veritable rubbish’ which did the cause ‘great harm’-and insisted that he had got ’not a fact or idea’ from Larnarck.13

-

“I worked on true Baconian principles and without any theory, collected facts on a wholesale scale … After five years’ work I allowed myself to speculate on the subject and drew up some short notes.” -Darwin

-

As Darwin’s own notebooks show, the last two sentences in this account again should not be taken at face value-they are pious lip service to the fashionable image of the scientist collecting facts ‘with an unprejudiced mind’, without permitting himself, God forbid, to speculate on them. In reality, as the notebooks show, shortly after his return from the voyage (and not ‘five years later’), Darwin became committed to the evolutionary theory-and then set out to collect facts to prove it. A month after publication of The Origin, in December 1859, he admitted this-apparently forgetting what he had said in the Preface-in a letter eloquently defending the procedure of ‘inventing a theory and seeing how many classes of facts the theory would ex plain’ .14 In another letter he remarks that ’no one could be a good observer unless he was an active theorizer’ ; and again: ‘How odd it is that anyone should not see that all observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service.‘15

page 139:

- Darwin himself, as one of his biographers remarked, ‘was able to give ultimate answers because he asked ultimate questions. His colleagues, the systematizers, knew more than he about particular species and varieties, comparative anatomy and morphology. But they had deliberately eschewed such ultimate questions as the pattern of creation, or the reasons for any particular form, on the grounds that these were not the proper subjects of science. Darwin, uninhibited by these restrictions, could range more widely and deeply into the mysteries of Nature. … It was with the sharp eyes of the primitive, the open mind of the innocent, that he looked at his subject, daring to ask questions that his more learned and sophisticated colleagues could not have thought to ask’ (Himmelfarb).22

· 1_07: Thinking Aside

page 146:

- In the popular imagination these men [like Einstein, Plank, etc] of science appear as sober ice-cold logicians, electronic brains mounted on dry sticks. But if one were shown an anthology of typical extracts from their letters and autobiographies with no names mentioned, and ·then asked to guess their profession, the likeliest answer would be: a bunch of poets or musicians of a rather romantically naive kind.

page 147:

- Max Planck, the father of quantum theory, wrote in his autobiography that the pioneer scientist must have ‘a vivid intuitive imagination for new ideas not generated by deduction, but by artistically creative imagination’.

page 148:

- what is remarkable is that this knowledge [a literally ancient theory of the mind] was lost during the scientific revolution, more particularly under the impact of its most influential philosopher, Rene Descartes, who flourished in the first half of the seventeenth century.

page 160:

- On another occasion I read about the acquittal of a woman who had been tried for the mercy-killing of her malformed baby; Galton was summoned because he had invented the word ’eugenics’; next came, logically, the ‘most nearly allied’ idea of Adolf Hitler, whose S.S. men practiced eugenics after their own fashion.

page 164:

- Among chosen combinations the most fertile will often be those formed of elements drawn from domains which are far apart… Most combinations so formed would be entirely sterile; but certain among them, very rare, are the most fruitful of all. -Henri Poincare

page 166:

- a negative insight into the narrow limitations of conscious thinking; and on the positive side, affirmations of the superiority of unconscious mentation at certain stages of creative work.

page 169:

- The dreamer floats among the phantom shapes of the hoary deep; the poet is a skin diver with a breathing tube.

page 175:

-

Einstein could never have transformed man’s view of the universe, had he accepted those two words as ready-made tools. ‘When I asked myself’, he confided to a friend, ‘how it happened that I in particular discovered the Relativity Theory, it seemed to lie in the following circumstance. The normal adult never bothers his head about space time problems. Everything there is to be thought about, in his opinion, has already been done in early childhood. I, on the contrary, developed so slowly that I only began to wonder about space and time when I was already grown up. In consequence I probed deeper into the problem than an ordinary child would have done.‘3° Modesty can hardly be carried further; nor insight put into simpler terms.

-

‘For me [the Relativity Theory] came as a tremendous surprise’, said Minkovsky, who had been one of Einstein’s teachers, ‘for in his student days Einstein had been a lazy dog. He never bothered about mathematics at all…

page 176:

- words can also become snares, decoys, or strait-jackets.

· 1_08: Underground Games

page 179:

- Lastly, I must mention the obvious fact of the dreamer’s extreme gullibility. Hamlet’s cloud merely resembles a camel, weasel, or whale; to the dreamer the cloud actually becomes a camel, a weasel, or whale-without his turning a hair.

- A child, watching a television thriller with flushed face and palpitating heart, praying that the hero should realize in time the deadly trap set for him, is at the same time aware that the hero is a shadow on the screen.

page 188:

- Psychotherapy in its modern form expresses in explicit terms the principle of ab-reaction, of the mental purge, which has always been implied in the ancient cathartic techniques from the Dionysian and Orphic mystery-cults to the rites of baptism and the confessional.

page 190:

- To undo wrong connections, faulty integrations, is half the game. To acquire a new habit is easy, because one main function of the nervous system is to act as a habit-forming machine; to break out of a habit is · an almost heroic feat of mind or character.

page 192:

- For once, however, Freud did not seem to have probed deep enough; he did not mention the rites of the Saturnalia and other ancient festivals, in which the roles of slaves and masters are reversed

page 194:

- As Lenin has said somewhere; ‘If you think of Revolution, dream of Revolution, sleep with Revolution for thirty years, you are bound to achieve a Revolution one day.’

page 210:

- The most fertile region seems to be the marshy shore, the borderland between sleep and full awakening where the matrices of disciplined thought are already operating but have not yet sufficiently hardened to obstruct the dreamlike fluidity of imagination.

page 211:

- To p. 210. ‘… Einstein has reported that his profound generalization connecting space and time occurred to him while he was sick in bed. Descartes is said to have made his discoveries while lying in bed in the morning and both Cannon and Poincare report having got bright ideas when lying in bed unable to sleep-the only good thing to be said for insomnia! It is said that James Brindley, the great engineer, when up against a difficult problem, would go to bed for several days till it was solved. Walter Scott wrote to a friend: ' “The half-hour between waking and rising has all my life proved propitious to any task which was exercising my invention. . . . It was always when I first opened my eyes that the desired ideas thronged upon me."’ (Beveridge, W. I. B., 1950, pp. 73-4)

· 1_09: The Spark and the Flame

page 218:

-

In the spring of 1884 Freud -then twenty-eight-read in a German medical paper that an Army doctor had been experimenting ‘with cocaine, the essential constituent of coca leaves which some Indian tribes chew to enable them to resist privations and hardships’. He ordered a small quantity of the stuff from a pharmaceutical firm, tried it on himself, his sisters, fiancée, and patients, decided that cocaine was a ‘magical drug’, which procured ’the most gorgeous excitement’, left no harmful after-effect, and was not habit-forming! In several publications he unreservedly recommended the use of cocaine against depression, indigestion, ‘in those functional states comprised under the name of neurasthenia’, and during the withdrawal-therapy of morphine addicts; he even tried to cure diabetes with it. ‘I am busy’, he wrote to his future wife, ‘collecting the literature for a song of praise to this magical substance.’ One is irresistibly reminded of Aldous Huxley’s songs of praise to mescaline; but Huxley was neither a member of the medical profession nor the founder of a new school in psychotherapy.

-

Two years after the publication of his first paper on the wonder-drug Knapp, the great American ophthalmologist. greeted Freud ‘as the man who had introduced cocaine to the world, and congratulated him on the achievement. In the same year, 1886, however, cases of cocaine addiction and intoxication were being reported from all over the world, and in Germany there was a general alarm. …9 The man who had tried to benefit humanity or at all events to create a reputation by curing “neurasthenia” was now accused of unleashing evil on the world.’

page 220:

- Watson conditioned an infant to say ‘da’ whenever it was given the bottle, starting at five months, twenty days-that is, six months earlier than the first words normally appear. The process took more than three weeks

page 221:

· 1_10: The Evolution of Ideas

page 232:

- An original mind, never wholly contained in any one conventionally enclosed field of interest, now seizes upon the possibility that there may be some unsuspected overlap, takes the risk whether there is or not, and gives the old subject-matter a new look.

page 233:

- As T. H. Huxley has said in an oft-quoted passage : Those who refuse to go beyond fact rarely get as far as fact; and anyone who has studied the history of science knows that almost every step therein has been made by… the invention of a hypothesis which, though verifiable, often had little foundation to start with…

page 235:

- New facts alone do not make a new theory; and new facts alone do not destroy an outlived theory. In both cases it requires creative originality to achieve the task.

page 237:

- In his treatise ‘On the Face in the Disc of the Moon’ Plutarch, who took a great interest in science and particularly in astronomy, wrote that the moon was of solid stuff, like the earth; and that the reason why it did not fall down on the earth, in spite of its weight, was as follows:

- …The moon has a security against falling in her very motion and the swing of her revolutions, just as objects put in slings are prevented from falling by the circular whirl ;for everything is carried along by the motion natural to it if it is not deflected by anything else. Thus the moon is not carried down by her weight because her natural tendency is frustrated by her revolution. 12 (my italics)

- The translation is by Heath, who remarks: ‘This is practically Newton’s first Law of Motion.’

page 243:

-

To quote Polanyi:

-

“For many prehistoric centuries the theories embodied in magic and witchcraft appeared to be strikingly confirmed by events in the eyes of those who believed in magic and witchcraft. … The destruction of belief in witchcraft during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was achieved in the face of an overwhelming, and still rapidly growing body of evidence for its reality. Those who denied that witches existed did not attempt to explain this evidence at all, but successfully urged that it be disregarded. Glanvill, who was one of the founders of the Royal Society, not unreasonably denounced this proposal as unscientific, on the ground of the professed empiricism of contemporary science. Some of the unexplained evidence for witchcraft was indeed buried for good, and only struggled painfully to light two centuries later when it was eventually recognized as the manifestation of hypnotic powers.18

page 244:

- Miller devoted his life to disproving Relativity-and on face value, so far as experimental data are concerned. he succeeded.* A whole generation later, W. Kantor of the U.S. Navy Electronics Laboratory repeated once more the ‘crucial experiment’. Again his instruments were far more accurate than Miller’s, and again they seemed to confirm that the speed of light was not independent from the motion of the observer – as Einstein’s theory demands. And yet the majority of physicists are convinced-and I think rightly so-that Einstein’s universe is superior to Newton’s.

page 245:

- my late friend Erwin Schrodinger

- Dirac concludes:“I think there is a moral to this story, namely that it is m o re important to have beauty in one’s equations than to have them fit experiment…."

page 248:

- ‘Environment’ to Pasteur meant the whole range of conditions from proper sanitation, through aseptic surgery, to the patient’s bodily and mental state. Much of this has become a fashionable truism today, but it was not in the days of Victorian medicine; and even today the lesson has not sunk in sufficiently, otherwise the mass- production of ‘super-hygienic’ food in sterilized wrappings would be recognized as detrimental to man’s internal environment-by depriving it of the immunizing effect of ingesting a healthy amount of muck and bugs.

page 249:

- The bubble chamber is a kind of aquarium window into the sub atomic world. It provides us with photographs of the condensation trails, like jet trails in the sky, of what we take to be the elementary particles of matter: electrons, neutrons, mesons, muons, etc., of some forty different varieties. But the particles themselves can of course never be seen, their inferred lifespan often amounts to no more than a millionth of a millionth second, they ceaselessly. transform them selves into different kinds of particles, and the physicists ask us to renounce thinking of them in terms of identity, causality, tangibility, or shape-in a word, to renounce thinking in intelligible terms, and to confine it to mathematical symbols.

page 253:

- The history of science shows recurrent cycles of differentiation and specialization followed by reintegrations on a higher level; from unity to variety to more generalized patterns of unity-in-variety.

· 1_11: Science and Emotion

page 262:

-

‘I see everywhere in the world the inevitable expression of the concept of infinity. It establishes in the depths of our hearts a belief in the supernatural. The idea of God is nothing more than one form of the idea of infinity. So long as the mystery of the infinite weighs on the human mind, so long will temples be raised to the cult of the infinite. whether God be called Brahmah, Allah, Jehovah or Jesus. . . . The Greeks understood the mysterious power of the hidden side of things. They bequeathed to us one of the most beautiful words in our language-the word ‘enthusiasm’ -en theos- a god within. The grandeur of human actions is measured by the inspiration from which they spring. Happy is he who bears a god within-an ideal of beauty and who obeys it, an ideal of art, of science. All are lighted by reflection from the infinite.’ -Pasteur

-

A contemporary has said, not unrightly, that the serious research scholar in our generally materialistic age is the only deeply religious human being. -Einstein

page 264:

- Modem man lives isolated in his artificial environment, not because the artificial is evil as such, but because of his lack of comprehension of the forces which make it work–of the principles which relate his gadgets to the forces of nature, to the universal order.

page 266:

- the paradoxes, the ‘blocked matrices’ which confronted Archimedes, Copernicus, Galilee, Newton, Harvey, Darwin, Einstein should be reconstructed in their historical setting and presented in the f o rm of riddles-with appropriate hints-to eager young minds. The most productive form of learning is problem-solving

Part Three: The Artist

· 1_12: The Logic of the Moist Eye

page 275:

- the pleasurable experience is derived not from anticipating, but from imagining the reward

page 278:

- When a woman weeps in sympathy with another person’s sorrow (or joy), she partially identifies herself with that ·person by an act of projection, introjection, or empathy-whatever you like to call it. The same is true when the ‘other person’ is a heroine on the screen or in the pages of a novel.

- the fact that the subject has for the moment more or less forgotten her own existence and participates in the existence of another, at another place and time.

page 279:

- The anxiety which grips the spectator of a thriller-film, though vicarious, is nevertheless real; it is reflected in the familiar physical symptoms-palpitations, tensed muscles, sudden ‘jumps’ of alarm.

· 1_13: Partness and Wholeness

· 1_14: On Islands and Waterways

page 295:

- Symbiotic consciousness wanes with maturation, as it must; but modem education provides hardly any stimuli for awakening cosmic consciousness to replace it. The child is taught petitionary prayer instead of meditation, religious dogma instead of contemplation of the infinite; the mysteries of nature are drummed into his head as if they were paragraphs in the penal code. In tribal societies puberty is a signal for solemn and severe initiation rites, to impress upon the individual his collective ties, before he is accepted as a part in the social whole.

page 300:

-

The shadows in Plato’s cave are symbols of man’s loneliness;

-

I don’t think so; they are seen trees in an unseen forest. The lies, the day-to-day going ons of life that hide the larger picture. They are a fake, accepted, reality. Actually I’d say they are the total opposite of loneliness. By engaging the real shadow world, socializing, material pursuits, hedonism, you are part of the group; most people walk this path. To go up and out of the cave, to walk the path of philosophy, is loneliness.

· 1_15: Illusion

page 302:

-

In fact all marathon TV serials with fixed settings and regular characters are cunningly designed to turn the viewer into an addict.

-

When the buxom Elsie Tanner was involved with a sailor who, unknown to her, was married, she got scores of letters warning her of the danger. Jack Watson, the actor who played the sailor, was stopped outside the studio by one gallant mechanic who threatened to give him a hiding if he didn’t leave Elsie alone.

-

The strongest personality of them all, the sturdy old bulldog bitch, Ena Sharples, has a huge following. When she was sacked from the Mission Hall of which she was caretaker, viewers from all over the country wrote offering her jobs. When she was in hospital temporarily bereft of speech, a fight broke out in Salford between a gang of her fans and an Irish detractor who said he hoped the old bag would stay dumb till Kingdom come.

page 303:

-

Moreover, when one of the seven houses on the set became ‘vacant’ because its owner was said to have moved-in fact because the actor in question had been dropped from the programme-there were several applications for renting the house; and when at a dramatic moment of the serial the barmaid in the ‘Rover’s Return’ smashed an ornamental plate, several viewers sent in replacements to comfort her.

-

The unconscious mind, the mind of the child and the primitive, are indifferent to it [the contradiction that the TV show is both real and fake to them]. So are the Eastern philosophies which teach the unity of opposites, as well as Western theologians and quantum physicists.

-

Comparing the suspension of disbelief when viewing television to Eastern religion and quantum physics. These aren’t fools, they simply know how to fool.

page 304:

- Laughter explodes emotion; weeping is its gentle overflow;

- Children and primitive audiences who, forgetting the present, completely accept the reality of the events on the stage, are experiencing not an aesthetic thrill, but a kind of hypnotic trance; and addiction to it may lead to various degrees of estrangement from reality.

- Liberated from his frustrations and anxieties, man can turn into a rather nice and dreamy creature;

page 309:

- there is only one step to the goat dance of the Achaeans, the precursor of Greek drama. ‘Tragedy’ means ‘goat-song’ (tragos = he goat, oide = song); it probably originated in the ceremonial rites in honour of Dionysus, where the performers were disguised in goat-skins as satyrs,

· 1_16: Rhythm and Rhyme

page 311:

- Needless to say, even the contemporary Rock-’n’-Roll or Twist are restrained and sublimated displays compared to the St. Vitus’s dance which spread as an infectious form of hysteria through medieval Europe.

page 312:

- We are more susceptible to musical tones than to noises, because the former consist of periodical, the latter of a-periodical air-waves.

· 1_17: Image

page 330:

-

The scientist feels the urge to confess his indebtedness to unconscious intuitions which guide his theorizing; the artist values, or over-values, the theoretical discipline which controls his intuition.

-

On the ‘beauty’ of mathematics versus the artists searching for golden ratios, laws of perspective, etc.

page 331:

-

the experience of truth, however subjective, must be present for the experience of beauty to arise; and v-ice versa, the solution of any of ’nature’s riddles’, however abstract, makes one exclaim ‘how beautiful’.

-

Thus, to heal the crack in the Grecian urn and to make it acceptable in this computer age we would have to improve on its wording (as Orwell did on Ecclesiastes) : Beauty is a function of truth, truth a function of beauty. They can be separated by analysis, but in the lived experience of the creative act-and of its re-creative echo in the beholder-they are inseparable as thought is inseparable from emotion.

page 332:

· 1_18: Infolding

page 333:

- From antiquity until well in to the Renaissance artists thought, or pro fessed to think, that they were copying nature; even Leonardo wrote into his notebook ’that painting is most praiseworthy which is most like the thing represented’. Of course, they were doing nothing of the sort. They were creating, as Plato had reproached them, ‘man-made dreams for those who are awake’.

page 337:

- One is a trend towards more pointed emphasis; the other towards more economy or implicitness. The first strives to recapture the artist’s waning mastery over the audience by providing a spicier fare for jaded appetites: exaggerated mannerisms, frills, flamboyance, an overly explicit appeal to the emotions, ‘rubbing it in’-symptoms of decadence and impotence, which need not concern us further.

page 341:

-

The witch-doctor hypnotizes his audience with the monotonous rhythm of his drum; the poet merely provides the audience with the means to hypnotize itself.

-

Reminds me of burning man’s joke about self serve, here you wash your own brain.

page 343:

-

The escapist character of illusion facilitates the unfolding of the participatory emotions and inhibits the self-asserting emotions, except those of a vicarious character; it draws on untapped resources of emotion and leads them to catharsis.

-

This perfectly sums up modern media: escapist, inhibiting self-assertion by channeling it vicariously into the screen, catharsis. I think a more and more common example is the superhero film; it checks all three boxes.

· 1_19: Character and Plot

page 346:

- I am always annoyed when the author informs me that Sally Anne has auburn hair and green eyes. I don’t particularly like the combination, and would have gone along more willingly with the author’s intention that I should fall in love with Sally Anne if he had left the colour-scheme to me. There is a misplaced concreteness which gets in the way of the imagination.

· 1_20: The Belly of the Whale

· 1_21: Motif and Medium

page 367:

-