Home · Book Reports · 2017 · The Craft of Research

- Author :: Wayne C. Booth & Gregory G. Colomb & Joseph M. Williams

- Publication Year :: 1995

- Read Date :: 2017-04-18

- Source :: The_Craft_of_Research.pdf

designates my notes. / designates important.

pdf page numbers

page 59:

- start in the library. Look at the headings in a general bibliography such as the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature.

page 69:

- To summarize: Your aim is to explain

-

what you are writing about—your topic: I am studying…

-

what you don’t know about it—your question: because I want to find out…

-

why you want your reader to know about it—your rationale: in order to help my reader understand better…

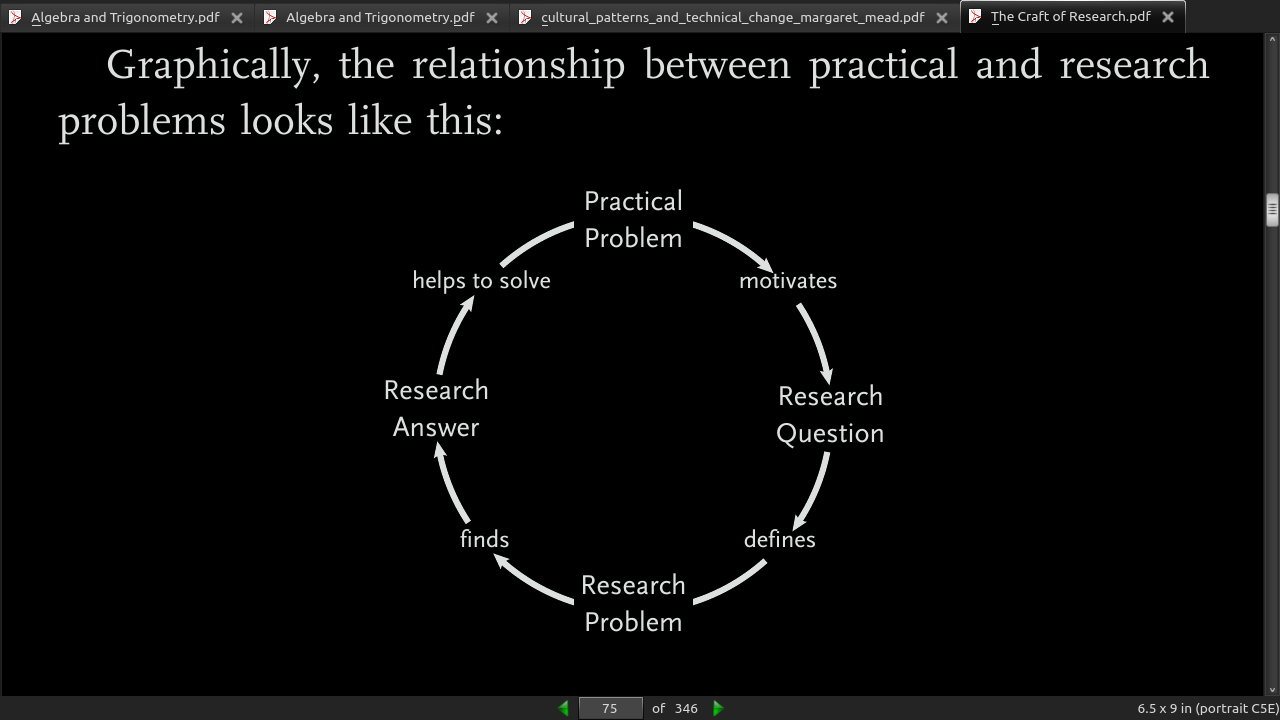

page 75:

page 114:

-

Record Complete Bibliographical Data Before you start taking notes, record all bibliographical data. We promise that no habit will serve you better for the rest of your career. For printed texts, record:

-

author,

-

title (including subtitle),

-

editor(s) (if any),

-

edition,

-

volume,

-

place published,

-

publisher,

-

date published,

-

page numbers of articles or chapters.

-

Online add:

-

URL,

-

date of access,

-

Webmaster (if identified),

-

database (if any).

page 121:

- (If you type keywords with an asterisk—*outpost civilizations—you can target your search more easily.)

page 135:

- We now have the core of a research argument: Claim because of Reason based on Evidence

page 138:

page 141:

-

Here are just a few of the different kinds of evidence to watch for in different fields:

-

personal beliefs and anecdotes from writers’ own lives, as in a first-year writing course;

-

direct quotations, as in most of the humanities;

-

citations and borrowings from previous writers, as in the law;

-

fine-grained descriptions of behavior, as in anthropology;

-

statistical summaries of behavior, as in sociology;

-

quantitative data gathered in laboratory experiments, as in natural sciences;

-

photographs, sound recordings, videotapes, and films, as in art, music, history, and anthropology;

-

detailed documentary data assembled into a coherent story, as in some kinds of history or anthropology;

-

networks of principles, implications, inferences, and conclusions independent of factual data, as in philosophy.

page 146:

- be clear about the kind of claim you intend to support: conceptual or practical.

page 156:

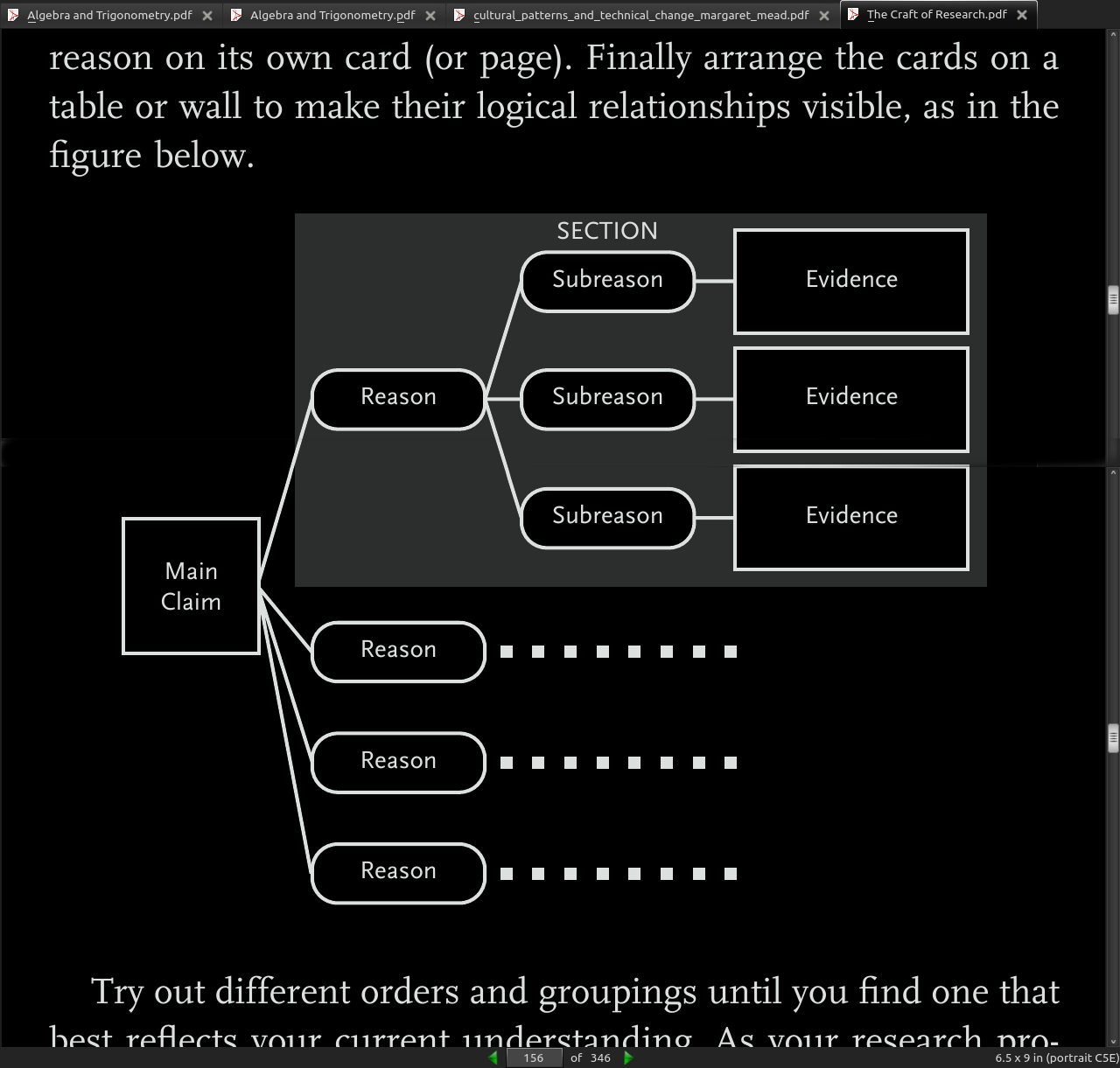

page 171:

- In sum: A crucial step in assembling your argument is to test it as your readers will, even in ways they might not, and then to acknowledge and respond to at least the most important objec- tions that you can imagine them raising.

page 173:

- So if you focus on one cause out of many, acknowledge the others

page 189:

- A good principle is to create a warrant that is only a bit more general than the reason and claim, and that does not depend on words like everyone, any, never, and always.

page 190:

- But when someone says your claim is unwarranted, or refers to it by the Latin term non sequitur (“it doesn’t follow”), you have to analyze the logic of your argument.

page 203:

- some researchers seem never to be able to finish; they think they have to keep working until their report, article, dissertation, or book is perfect. No such perfect document exists, ever has, or ever will. All you can do is to make your report as complete and as close to right as you can, given the time avail- able.

page 206:

- Nothing is easier than putting off a first draft: Just another week of reading, you think, another day, an hour; as soon as I finish this cup of coffee.

page 207:

-

Once they have a plan, many writers draft as fast as they can make pen or keys move. Not worrying about style or even clarity, and least of all perfect grammar and spelling, they try to keep up the flow of ideas. If a section bogs down, they note where, check their outline, and move on. If they are on a roll, they don’t bother typing out quotes or footnotes: they cite just enough to know what to add later. Then if they freeze up, they have things to do: add quotes, fill in long quotations, make sure the bibliography includes every source—whatever diverts them from what is blocking them but keeps them on task, giving their subconscious a chance to work on the problem. Or they take a walk.

-

Others can write only sentence by polished sentence. If you cannot imagine a quicker but rougher style of drafting, don’t fight it. But remember: The more small pieces you nail down early, the less you can move them around later. If you try to make large-scale revisions, you’ll face a big problem…

-

Whatever your style, create a ritual for writing. Set daily time commitments and page goals. Ritualistically straighten up your desk, sharpen your pencils or boot up your computer, get the light just right. Don’t check e-mail or start up your browser. Re- solve that you will sit there writing for at least a minimum time, whether the words that come seem brilliant or dull.

page 209:

- “quilting,” stitching together quotations from dozens of sources in a design that reflects little of your own thinking.

page 214:

-

Old to New. In general, readers prefer to move from what they know to what they don’t. Take this principle as a general guide when you are stuck: Start with what’s familiar to your readers, then move to the unfamiliar.

-

Shorter and Simpler to Longer and More Complex. In general, readers also prefer to deal with shorter, less complex reasons before longer, more complex ones. Start with the elements of your argument that readers will understand most easily. The easiest parts are likely to be more familiar as well.

page 215:

-

Uncontested to More Contested. In general, readers move more easily from less contested to more contested issues. If your main claim is controversial and you can present several arguments to support it, try starting with the one your reader is most likely to accept.

-

Consider these possible orders, as well:

-

chronological order;

-

logical order, from evidence to reason to claim, or vice versa;

-

concessions and conditions first, then an objection you can rebut, then your own affirmative evidence, or vice versa.

-

Presiding over all your judgments must be this principle: What must your readers know before they can understand what comes next?

page 217:

- Research is like gold mining: dig up a lot, pick out a little, discard the rest. Even if all that material never appears in your report, it is the tacit foundation of knowledge on which your argument rests. Ernest Hemingway once said that you know you’re writing well when you discard stuff you know is good—but not as good as what you keep.

page 238:

- In years to come, some researcher may search for exactly the research you have done. That search will be done by a computer looking for keywords in titles and abstracts. So when you write yours, imagine looking for your own research. What words should a researcher look for? Put them in your title and abstract.

page 250:

-

You can state your solution explicitly. When you announce your main point in the introduction, you create a “point-first” paper (even though that point appears as the last sentence of the introduction).

-

Alternatively, you can put off stating your main point by stating only where your paper is headed, thereby implying that you will present your solution in your conclusion (review pp. 195–96). This approach provides a “launching point” and creates a “point- last” paper:

page 253:

- you can use the same elements that you used in your introduction for your conclusion. You just use them in reverse order.

page 254:

- So before you write your last words, imagine someone fascinated by your work who wants to follow up on it: What would you suggest they do? What more would you like to know?

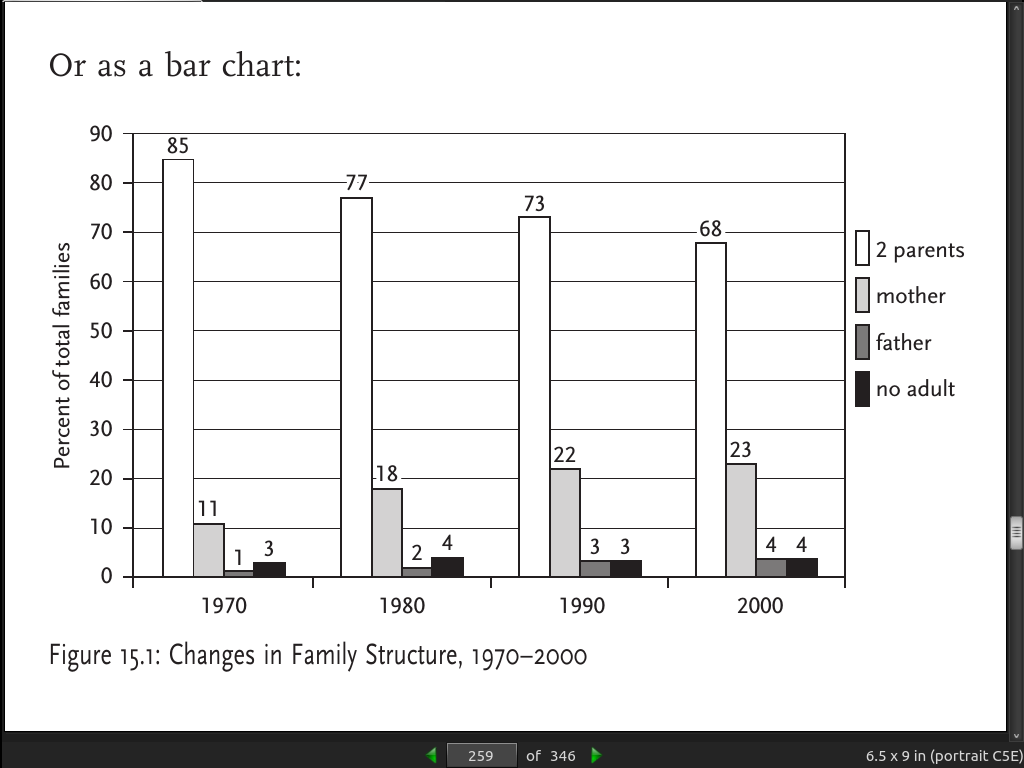

page 259:

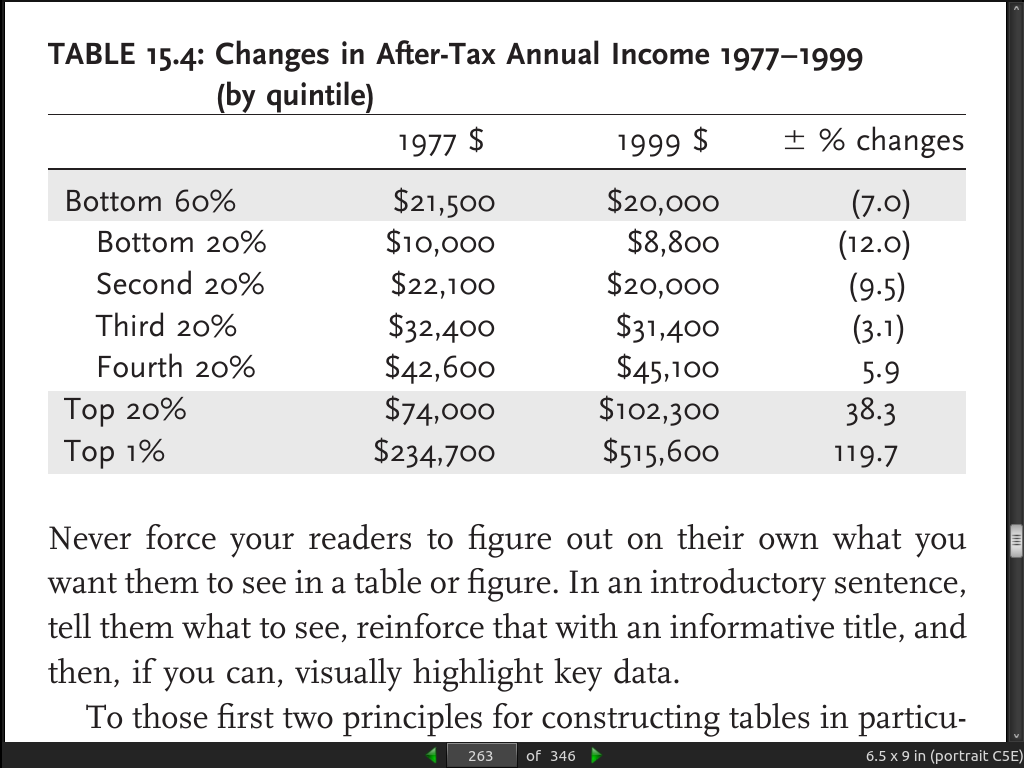

page 263:

page 292:

-

Look at the first six or seven words of every sentence.

-

Be certain that each opens with information that your readers will find familiar, easy to understand (usually words used before).

-

Put close to the ends of your sentences any information that your readers will find new, complex, harder to under- stand.

page 297:

- once you’ve checked the first six or seven words in every sentence, check the last five or six, as well. If those words are not the most important, complex, or weighty, revise so that they are.

page 310:

- Research is messy, so it does no good to march students through it lockstep: (1) Select topic, (2) state thesis, (3) write outline, (4) collect bibliography, (5) read and take notes, (6) write report. That caricatures real research.

page 321:

- Annual Review of Anthropology. Palo Alto, Calif.: Annual Reviews. Also available online at http://anthro.AnnualReviews.org/contents-by-date.0.shtml.

page 326:

- Annual Review of Psychology. Palo Alto, Calif.: Annual Reviews.

page 327:

- Annual Review of Sociology. Palo Alto, Calif.: Annual Reviews.

page 335:

- Almost every contestable issue in rhetoric begins with Plato’s Phaedrus and Gorgias (Gorgias/Plato, trans. Robin Waterfield [Ox- ford University Press, 1994]) and Aristotle’s Rhetoric (On Rheto- ric: A Theory of Civic Discourse, trans. George Kennedy [Oxford University Press, 1991]). The best discussion of what rhetoric is for is Eugene Garver’s Aristotle’s Rhetoric: An Art of Character (University of Chicago Press, 1994). Following Aristotle is Cice- ro’s De Oratore, trans. J. S. Watson (Southern Illinois Press, 1986); and De Inventione, trans. H. M. Hubbell (Harvard Univer- sity Press, 1976); and Quintilian’s Institutiones oratoriae, ed. James J. Murphy (Southern Illinois University Press, 1987).

page 336:

- To appreciate the extent of that explosion of interest in diverse “rhetorics” of different fields, you might go to the Library of Congress online and call up “the rhetoric of . . . ,” filling in your field of special interest. Since about 1950, more than six hundred titles have emerged relating rhetorical study to this or that academic discipline, …

page 338:

- For general accounts of problem solving and finding, the classic source is John Dewey’s How We Think (Heath, 1910).

page 339:

- Williams and Colomb’s The Craft of Argument, 2nd ed. (Addison-Wesley Longman, 2003).